In defense of ancestral memory

At the Frankfurt Book Fair, surrounded by agents and contracts and clauses about rights, I began to see memory in the same grammar as property. Who gets to keep a life story? Who gets to revise it? Who gets to erase it?

I have lived the domestic version of that fight. Six years ago, I cut off a cousin who, with the devotion of a priest saying Mass, repeated slander about my parents. Both of them are gone, my father since 1989, my mother since 2015, and the cousin decided to supply me with new memories to replace the ones I grew up with. She declared my father an alcoholic. I never once saw him drunk, not even with a glass. I left that side of the family to preserve my version of the man.

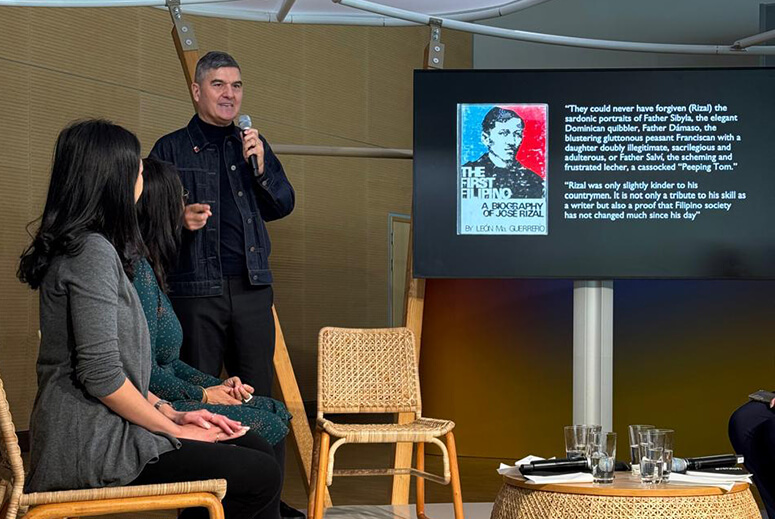

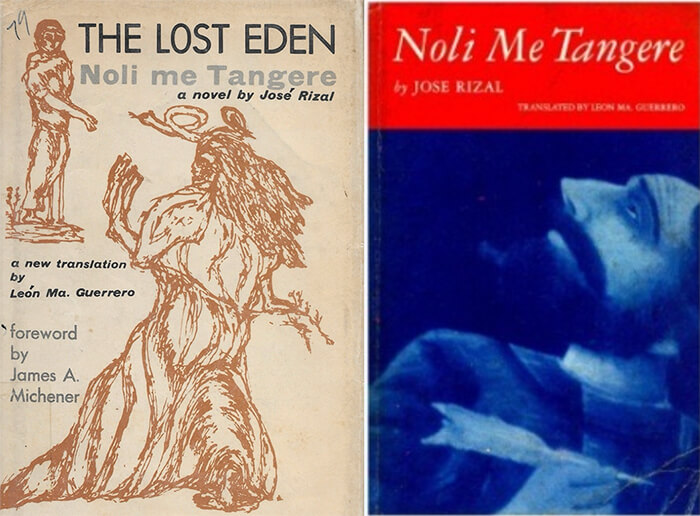

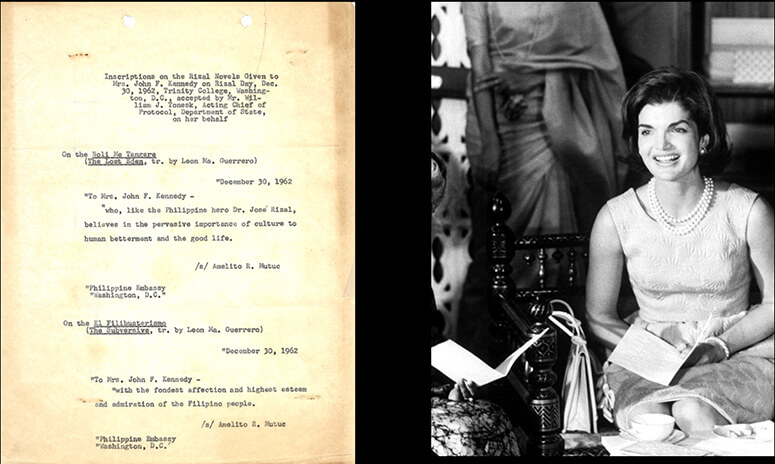

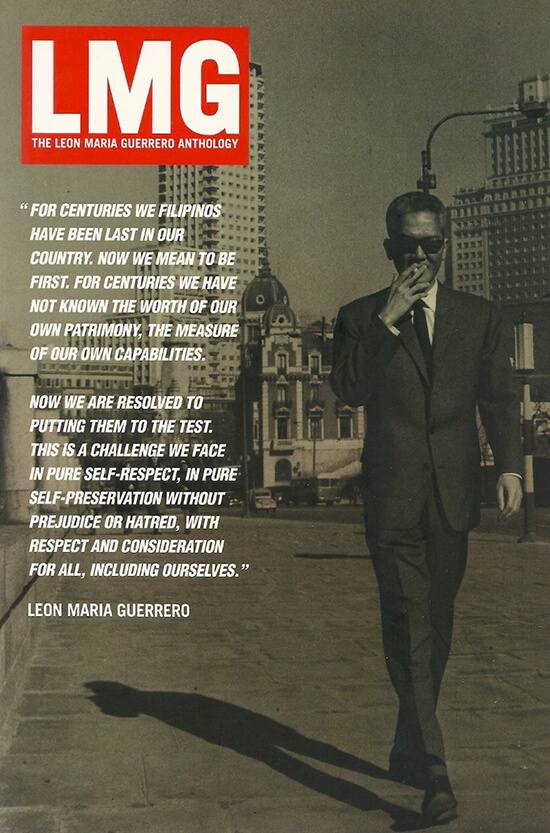

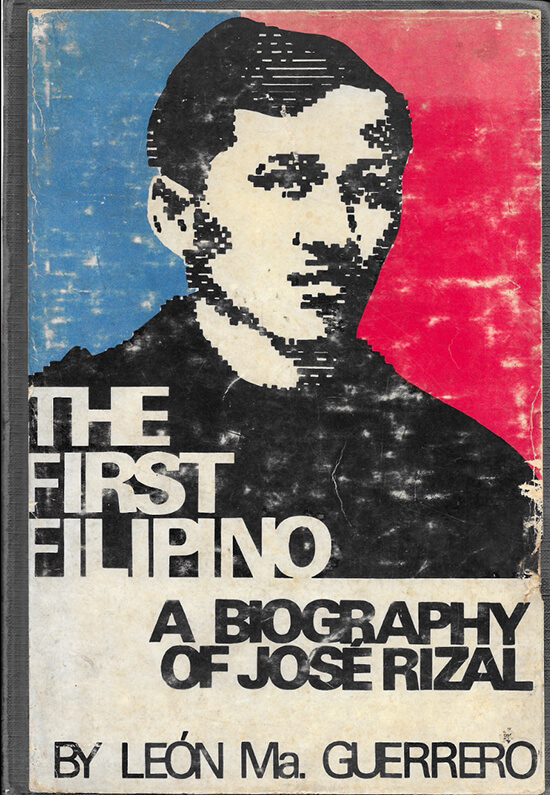

Private erasures are one thing. Public ones are another. Consider León María Guerrero, diplomat, novelist, translator of José Rizal. His English Noli Me Tangere and El Filibusterismo from the early 1960s were once praised without hesitation. The New Statesman called them “fresh and sensible.” In July 22, 1961, the New York Times wrote: “There have been various translations of the ‘Noli.’ The best known in English is by Charles Darbyshire. A Filipino writer and educator Jorge C. Bocobo published another in English, which was a remarkable job. This present translation by L.M. Guerrero is—in the opinion of this reviewer—the best of them all.” On the same day, the Saturday Review critiqued Guerrero’s work as “the first translation of Rizal’s novel in the US for nearly 60 years. That is an event in itself. But even more eventful is the vitality of Guerrero’s translation, which armors the old authenticity within a contemporary presence. Now, for the first time, action, humor, the passions are audible again, as they must have been for Rizal.” Then, three decades later, a blade came for them from the celebrated US-based Anglo-Irish historian Benedict Anderson, the author of Imagined Communities. In his essay “Hard to Imagine,” he publicly dismantled the translations.

His critique was not mild. Anderson called the translations a deliberate political distortion, a conscious alignment with the regime of 1950s respectability, achieved through demodernization and bowdlerization. That belongs to the arena of scholarship. But Anderson did not stay there. In print, he described Guerrero as “the alcoholic anti-American diplomat.”

David Guerrero, the son, the literary trustee, answered. He wrote to Anderson to protest a line that appeared without footnote, without evidence, like an epitaph. Anderson conceded that it was insulting and admitted it was written in haste. He kept his theory about the translation but withdrew the personal blow. In his email, he also wrote, “I learned a good deal from this book.” Anderson died in December 2015 and the exchange never resurfaced in his later work.

That confrontation is the clean illustration. One part is protected debate, the other part is personal stain. The first lives inside the freedom to argue about books. The second trespasses into the memory of the dead.

In the US or the UK, and many other places like Canada, Australia, New Zealand, India, Singapore and Hong Kong, that trespass is not actionable. The dead cannot be defamed there. They belong to the public. That is why Lincoln can hunt vampires and Oscar Wilde can solve the murder of male prostitutes in Victorian London and no heir can call a lawyer. In the Philippines, the dead do not lose their shield. Article 353 of the Revised Penal Code explicitly defines libel “as a public and malicious imputation of a crime, vice, or defect, real or imaginary, or any act, omission, condition, status, or circumstance tending to cause the dishonor, discredit, or contempt of a person, or to blacken the memory of one who is dead.” Our law on libel does make room for descendants to defend ancestral memory. You can attack the work. You cannot fabricate a vice and publish it like fact.

I flew back from Frankfurt and met the same quarrel at home, this time around Manuel L. Quezon and a film promoted as a biopic that carries the claim of biography. At the premiere, the filmmaker Jerrold Tarog, confronted by Quezon descendant Ricky Quezon Avanceña, tried to defend the work as satire. The distinction matters because fiction, even historical fiction, can take liberties while biography cannot invent.

The framework is clear. You are free to criticize, reinterpret, interrogate, dismantle. But when you accuse the dead of a vice or a moral defect and publish it as truth without a factual spine, you step into the zone where descendants are allowed to intervene.

Ideas can be attacked. Legacies cannot be blackened by invention. In a country where family forms the spine of identity, the law allows the living to guard the memory of the dead. It does not silence scholarship. It demands that even criticism must not rely on lies.

In Frankfurt, I watched people trade rights to stories. It made sense suddenly that the most contested rights are not those over books still being written, but those over lives already finished, whose authors can no longer answer back, except through the children and grandchildren who refuse to let someone else rewrite their last line.