Was it really a golden age? Myths on Ferdinand Marcos' martial law debunked

Nothing is as disputed and controversial in Philippine history as the late former president Ferdinand E. Marcos' martial law.

50 years later, the truth about martial law has been muddled in attempts to play down the horrendous human rights abuses that transpired during that dark period of Philippine history.

There are those who remember the brutal and corrupt reign, but the disinformation spreading like wildfire on social media seeks to erase these memories and revise history. Of the 326 fact checks done by Tsek.ph from November 2021 to February 2022, 58 were about the martial law era, the EDSA People Power Revolution, and the administrations of Marcos and Corazon Aquino. From these fact checks, the most viewed claim said no Marcos critic was arrested during his regime.

In the Philippines' long history, why is Marcos' controversial martial law one of the most disputed topics—with one side describing it as a "golden era" while others see it as a dark time?

Narratives, rooted in the past, especially when distorted to favor a specific person or family, can be powerful enough to rally people to them, and have themselves elected to power.

The root of the myths

"We lack the education in trying to learn what actually happened, that's the problem," historian and De La Salle University professor Jose Victor Torres told PhilSTAR L!fe. "1986 came and we drove Marcos away, they did nothing—they didn't teach martial law in our history classes."

Torres added that Filipinos were too focused on finally bringing back democracy that questions about martial law were put on the back burner.

However, numerous pieces of literature and films were published about the dictatorship–and even during it. Former press censor and chief propagandist Primitivo Mijares defected Marcos' side and testified against his abuses in his 1975 book The Conjugal Dictatorship.

For historian Kristoffer Pasion, the myths are widespread because of distorted narratives.

"Narratives, rooted in the past, especially when distorted to favor a specific person or family, can be powerful enough to rally people to them, and have themselves elected to power," he said.

"These narratives such as Duterte as the 'father figure' (Tatay Digong) or BBM as 'Kuya' whose father was strongman Marcos Sr., make these politicians relatable, and make people suspend rational processes, give in to emotion, and eventually believe the most spectacular things—to the point that when they encounter facts contrary to what they believe in, they would reject them."

As we commemorate the 50th year since martial law was implemented in the Philippines, let's debunk some widely believed myths about this era.

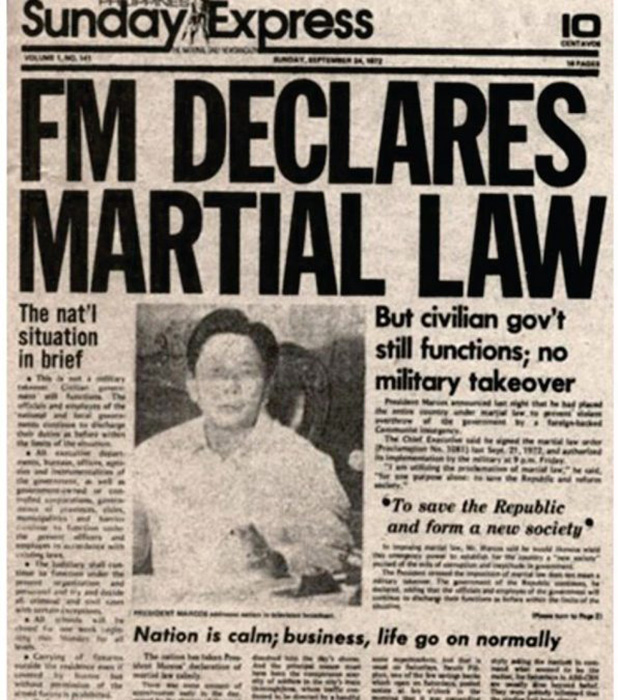

Myth: Martial law was declared on Sept. 21

Based on the Official Gazette's timeline, democracy was still alive on Sept. 21, 1972, and it was actually at 7:15 PM, Sept. 23 when Marcos appeared on TV to declare martial law.

"21 was divisible by seven. That's why Marcos wanted martial law declared on the 21st. He believed in numerology," Pasion explained.

Journalists and opposition leaders were arrested, and media outlets and TV stations were shut down on the 23rd.

In 2021, he wrote a thread on Twitter, insisting on aiming for accuracy. "Mahirap lang din isipin na tatlong dekada na pagkatapos niya mamatay, eh nasunod pa rin natin ang gusto niya based on numerology. #Never again to being duped tayo."

Myth: Martial law was a time of peace and prosperity

In the 60s, activists swarmed the streets as students questioned the roots of society's problems, inspired by ideas from nationalist Claro M. Recto. Student unrest peaked in 1970 with the First Quarter Storm, after Marcos was reelected.

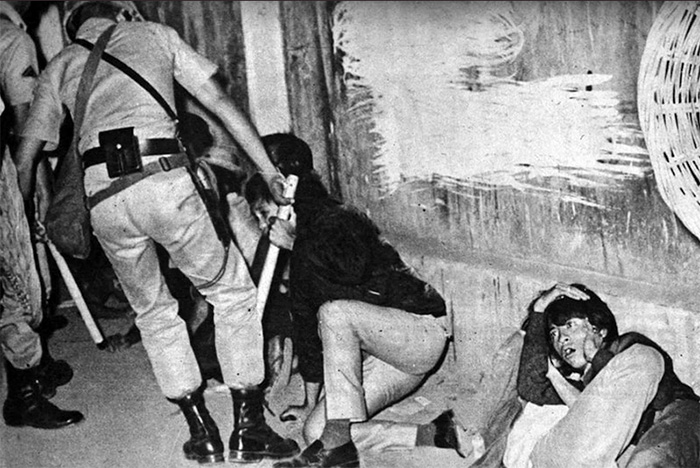

The demonstrations would continue until Sept. 23, when the ex-president appeared on TV, declaring martial law. Journalists and opposition leaders were rounded up, so the once loud streets were hushed.

"All of a sudden, maririnig mo talaga from those [alive] at the time, tumahimik daw. There was peace and order. Siyempre meron kasi everyone was arrested and thrown into jail," Torres said.

Amnesty International documented extensive human rights violations from 1972 to 1981, including 70,000 individuals imprisoned, 3,200 victims of extrajudicial killings, and 34,000 tortured.

"A lot of the opposition were arrested. The police really cracked down on criminality. It was basically a military takeover even though Marcos kept insisting it wasn't," the historian added.

Myth: Martial law was the golden age of the Philippines

During the early years of the Marcos administration, the economy went up, with the gross domestic product (GDP) growing at an average 6% growth per year from 1972 to 1980.

Infrastructure projects were developed like the Bataan Nuclear Powerplant, Philippine Heart Center, National Kidney and Transplant Institute, Lung Center of the Philippines, and more. First lady Imelda Marcos envisioned the Philippines as the "Cannes of Asia," thus building theaters like the Manila Film Center, Cultural Center of the Philippines complex, Philippine International Convention Center, and National Arts Center.

But as Torres puts it, "the cracks started to show" by the early 80s.

"What was not actually known until much later was talagang umutang [sila Marcos and Imelda]. They really sank the country in debt because of those projects," he continued.

From $0.36 billion in 1961, the country's debt skyrocketed to $28.26 billion by 1986.

Myth: $1=P1 during Marcos' era

When Marcos was first elected president in 1965, one US dollar was equivalent to P3.90, not one peso. And by the end of his reign in 1986, the value actually depreciated—one dollar would be P20.46.

Myth: 'Bata pa lang si Imee at BBM noong martial law'

In 2017, former president Rodrigo Duterte falsely claimed Marcos' children, Sen. Imee and President Ferdinand "Bongbong" Jr., were "too young" to have been complicit in the human rights abuses during their father's reign.

At the beginning of the military rule, Bongbong was 15 while Imee was 17 and by the end of it, they were 28 and 30. During martial law in 1980, the son followed in his father's footsteps in politics and became the vice governor of Ilocos Norte at 23.

Myth: If it weren't for Marcos, we wouldn't have OFWs

On May 1, 1974, Marcos implemented Presidential Decree 442, a labor code to push overseas contract work, making the myth partly true. The number of overseas workers did significantly increase from 36,035 in 1975 to 378,214 in 1986. The reason why Filipinos had to look for opportunities abroad, however, gets overlooked.

Pinoys couldn't earn enough to feed their families with the jobs they had in the country, as chronicled in a video by the National Historical Commission of the Philippines.

Six out of 10 families were poor by the end of Marcos' rule, with Filipino farmers earning only P30 per day in 1986. Prices of goods tripled by the last decade of martial law—the basic commodities that would cost P100 in 1976 cost more than P300 by the end of the regime.

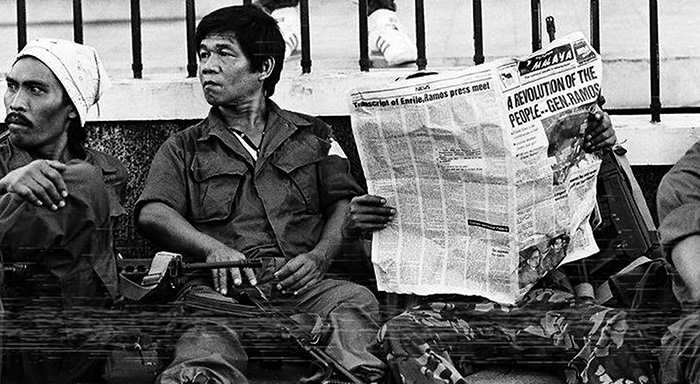

Myth: Marcoses left Malacañang calmly in 1986

In Darryl Yap's fictional retelling of the Marcoses' last days in the Malacañang Palace, it was portrayed that the family left calmly as they fled the country on the night of Feb. 25, 1986.

However, in reality, they rushed to put their things together. According to Angela Stuart-Santiago's Chronology of a Revolution, the former first family began packing their things at around 6 PM and they had two hours to leave the Palace.

In the book Ferdinand E: Marcos: Malacañang to Makiki, the ex-president's military aide Arturo Aruiza noted that the night was busy as the family's things were packed.

"The traffic between the bedroom upstairs and Heroes Hall below grew more frenzied as all kinds of luggage made their way down. There were carton boxes, garment bags, duffel bags, traveling bags, leather bags, attaché cases, Louis Vuitton bags, suitcases, and just plain boxes packed but their flaps left unsealed," he wrote.

"Back in the Palace that last night, things were in an uproar, all of us running around, grabbing at possessions, shouting last-minute instructions, trying to remember admonitions."

Myth: There was no suppression of press freedom during martial law

On Sept. 28, Marcos authorized the military to shut down major media outlets, including the ABS-CBN Network, Channel 5, and other broadcasting stations. He claimed the media outlets were "engaged in subversive activities against the government."

In 2007, former executive editor of the defunct Mirror Magazine Jennifer Santillan Santiago wrote about how challenging it was to be a journalist during martial law. It was an era of "press release journalism," she said as reporters could only publish press releases from the government. In addition, they couldn't conduct ambush interviews and instead had to make appointments to interview government officials.

Despite this, Marcos still maintained "there is no censorship at present" when he was interviewed on Sept. 20, 1974 on the NBC Today Show.

Fighting for the truth

For historians Torres and Pasion, the only way to battle these martial law myths is with the truth.

"The only way to battle the [historical distortion] on social media is with the truth. Right now, accessibility to social media is the same [for everyone]. It's getting the facts that are important," Torres said.

Pasion added that fact-checking alone is not enough and what is needed is "patient persuasion" through arts, humanities, and other creative means rooted in the truth.

"The battle should be through affect also. We must be ready to engage people with whatever means necessary, listening to where they are coming from, in order that we answer powerfully and effectively," he said.

"We've been too polarized. What we need is to break the barriers of our bubble to enter those who've been hooked, understanding things from their point of view, so that we can break the narrative they have been caught in. History not only provides facts, but context and understanding, which leads to empathy, accountability, and ultimately justice."