The big story that may unite us

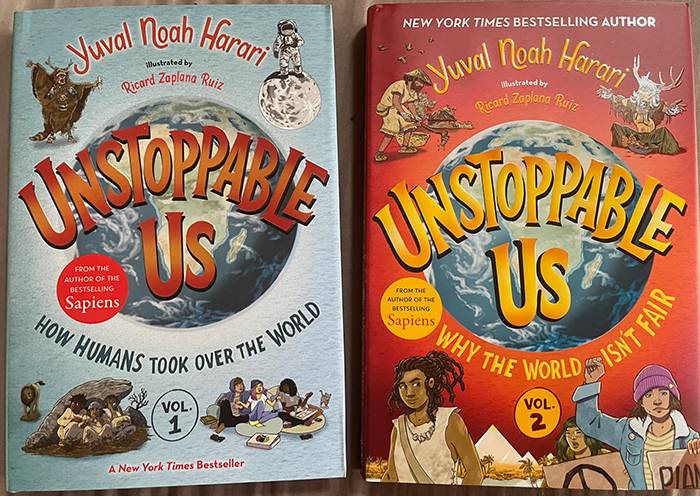

One of the best gifts I received over the holiday season was this boxed set of two volumes titled Unstoppable Us, written by Yuval Noah Harari and illustrated by Ricardo Zaplana Ruiz.

Available from Amazon, the New York Times bestseller intended for middle school readers (students aged 11 to 13 in the US, 12 to 16 here) tracks the early history of humankind—as a lucid, simplified but engaging presentation from a renowned historian and philosopher, whose previous book Sapiens was also a bestseller.

Published by Bright Matter Books of New York in 2022, the first volume is subtitled How Humans Took Over the World, while last year’s sequel is subtitled Why the World Isn’t Fair.

A diagram traces a “Timeline of History” starting 6 million years ago, marking the “Last common ancestor of humans and chimpanzees.” There’s a big jump to 2.5 million years ago when “Humans evolve in Africa” and the “Use of stone tools,” followed 2 million years ago by “Evolution of humans,” and after another half a million years, the “Earliest use of fire.”

Punctuating briefer gaps are the evolution of Neanderthals in Europe and the Middle East, then the evolution of Sapiens in Africa, and 70,000 years ago, the “Emergence of storytelling Sapiens (that) leave Africa in large numbers.” Another 20,000 years and the “Sapiens spread across Australia,” where big animals start to become extinct. 40,000 years ago marks “Development of Art, followed five millennia later by “Extinction of Neanderthals,” leaving Sapiens as the last surviving kind of human. And finally, 15,000 years ago, “Sapiens spread across the Americas.”

Leaping over the millennial gaps, the author engages with logical speculations on how humans take over the world. Cautionary counsel is clothed with simple allegories and analogies that are seldom far away from a touch of humor.

“To be a good human being, you need to understand the power you have and what to do with it. And for that, you need to know how we got our power in the first place. We humans aren’t as strong as lions, we don’t swim as well as dolphins, and we definitely don’t have wings! So how did we end up ruling the planet?”

Humans are animals and we used to be wild, writes Harari.

“Then one human had a great idea. She took a stone and used it to crack open a bone. Inside, she found the marrow—that’s the juicy stuff in the middle of bones. She ate the marrow and found it delicious. Other people saw what she had done and copied her. Soon everyone was using stones to crack bones and eat marrow. Humans finally had something that only they knew how to do!”

“… Even more important, humans learned that making tools is a good idea.” Also, after a time, “The way humans used fire made them unique.”

The diversification of the human family in different parts of the world has been traced by archeologists—from the small Floresians whose skeletons were found in a cave in Flores Island in what is now Indonesia, to Neanderthals from the Neander Valley in what became Germany, and the Denisovans whose bones were found in a cave in Siberia.

Meanwhile, our ancestors who lived mostly in Africa evolved into Homo sapiens, or Sapiens for short. Next stop for the “wise humans” was Super-Sapiens, whose slow spread from Africa reduced and eventually eliminated the Floresians, Neanderthals, and Denisovans.

The Sapiens’ superpower, as Harari puts it, was learning to cooperate in large numbers. “All the big achievements of humankind, such as flying to the moon, were the result of cooperation between hundreds of thousands of people.” And this superpower was the result of “our ability to dream up stuff that isn’t really there and to tell all kinds of imaginary stories. We’re the only animals that can invent and believe in legends, fairy tales, and myths.” That includes zombies, vampires, fairies, and gods.

With improving skills, cooperation and cunning, Sapiens spread all over the world, including Australia and America. Thus began the Extinction Express—with the largest animals like mammoths and mastodons becoming prey since they provided more food for larger numbers of human hunters.

“So that’s how we humans became the rulers of planet Earth.” This was well before learning how to write, building farms and cities, and eventually, spacecraft. “They couldn’t even grow wheat and make bread. So how did they learn to do all these things? That’s a whole other story.”

The sequel’s Timeline begins 25,000 years ago when “Wild wolves become domesticated dogs.” It took another 15,000 years before the domestication of sheep, pigs, cows, and cats, along with wheat, rice, and potatoes. The first cheese and first irrigation canal came 8,000 years ago, before writing was invented in Sumer 300 years later.

The author notes that in this second volume, “we explore how humans learned to control animals like dogs, chickens, and cows—and how some people also learned to control other people.”

This explains the subtitle, Why the World Isn’t Fair. It started with the plant that changed the world—cereals—and coming up with the idea that wheat could be better raised close to home. “It meant trying to control other living things.”

Followed the belief in spirits, which led to the spirit experts’ claim that this or that idea was suggested supernaturally. Priests and religions were the extended consequence, just as leadership and governments also became a way of controlling others. Of course it led to wars, as dictated by kings and religious leaders. Slavery, taxes, revolutions, you get the picture. And the world became not only unfair, but zany, often cruel.

Harari introduces fictional conversations between fictional characters to get his presentations across. It’s effective as if it is amusing. Rules and rewards. Who guards the guards? The author repeats his thesis that telling stories is still the greatest power that humans have.

“A human tribe with a good story was the most powerful thing in the world. … After the Agricultural Revolution, priests and chiefs used stories to convince people to work hard, build temples, and guard walls. As villages grew into cities and tribes grew into kingdoms, the stories also grew. Small tribes could manage with small stories, but to create a big kingdom you needed a big story.”

Rituals, flags, countries’ symbols, faith and veneration are all part of these stories, as are collective dreams. Eventually, ever so slowly, women gain the freedom they have long deserved, and same-gender relations also become acceptable. That’s when stories meet and gain more traction.

The final rhetoric goes: “How did people from different places manage to agree on anything? Did foreigners find some story they all believed? Or did they just fight all the time?

“Today, you can travel almost anywhere in the world, and everywhere you go, many of the rules are the same. People everywhere play soccer according to the same rules. People everywhere can use money to buy pineapples. People everywhere stop at a red light. How did this happen? How did some stories and rules spread all over the planet?

“Well, that’s a whole new story.”

We look forward to Harari’s next volume, one that is sure to be just as entertaining and edifying. There is much to discover and learn from his books, even for those of us now whose experience of middle school seems to have been all of a millennium ago.