Life beyond bars: Stories of hope from former prisoners

There is nothing more human than making mistakes; yet, our incarcerated brothers and sisters are often defined by their wrongdoings for the rest of their lives.

Prisoners are some of the most stigmatized members of society, from the moment they’re sentenced to the day they’re released, and even after that. The general consensus is that all those who find themselves behind bars for whatever reason must have inflicted enough suffering on others to deserve this form of punishment. And as dictated by our culture of fear, old habits die hard; people like them are permanently incapable of redemption and change.

Since its establishment in 1994, the Philippine Jesuit Prison Service Foundation, Inc. has worked towards combatting this regressive way of thinking. This nonprofit run by the Philippine province of the Society of Jesus provides holistic rehabilitation services as well as comprehensive forms of support to the corrections community. Their practice is sustained by the belief that anyone can have a second chance, regardless of their past.

Every last week of October, the organization celebrates Prison Awareness Week, an event that encourages us all to remember those who languish in our jails and rethink our definitions of prison: to see them not as a weapon but as a way towards reformation. Hopefully, these three former PDLs (persons deprived of liberty) can serve as living proof that life goes on even beyond bars.

PJ Ballon

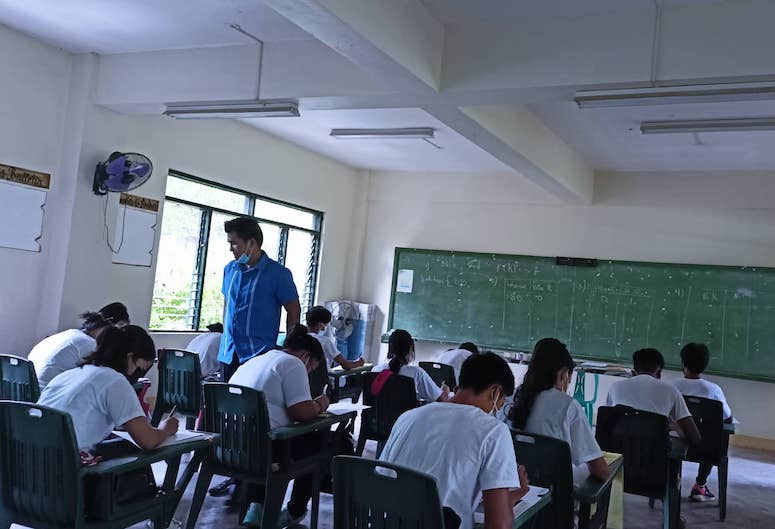

The return of onsite classes poses new challenges to faculty members, especially those who joined the workforce during the pandemic. When PhilSTAR Li!fe asked PJ Ballon how he manages to handle two batches of rowdy and impatient students, he shrugs it off and says, “Patience talaga yung isa sa major na natutunan ko sa loob ng kulungan. Kung kinaya ko ngang pagpasensyahan yung mga presong nakasama ko ng ilang taon, siguro wala lang sakin yung pag-handle ng mga bata.”

Yes, this senior high teacher was in jail – and school also played a part in his story.

In 2006, Ballon was a Grade 6 graduate looking for a chance to turn his life around; thankfully, a college professor saw promise in him and offered to take care of his studies. “Ang inisip ko na lang noon, ‘sino ba naman ako para humindi?’,” he recalled. But his chance at a bright future took a dark turn when his supposed mentor tried to rape him during a drunken encounter. In an attempt to defend himself, Ballon killed him.

Prisoners jailed for such grave offenses are deprived of certain privileges and even more devoid of human contact for security purposes. But Ballon was an exception, often assisting the wardens in “indoctrinating” new PDLs into the facility. Because of his exemplary behavior, he was offered an opportunity to pursue his studies up to college.

“Nagpapasalamat ako na merong mga jail guard na pinagtuunan din nila yung reformation na aspect ng pagkulong sa amin,” he said. “Naniwala sila na kapag kinulong lang kami, babalik at babalik lang yung mga katulad namin. Pero pag tinuruan nila kami ng mga bagay na makakapagpabago ng buhay namin, na magagamit namin kapag nakalaya na kami, mas mataas yung posibilidad na aangat kami sa buhay.”

Ballon graduated with a degree in entrepreneurship in May 2018 and found himself back in the outside world three months later. Now, he pursues a career in education, teaching everything from statistics and applied economics to Philippine politics and governance. “Pakiramdam ko naging advantage ko pa sa pagtuturo ko yung experience ko kasi alam ko kung paano ituro yung tama sa mali,” he shared.

Firsthand ko kasing na-experience yung consequences ng pagkakamali sa buhay, kaya sobrang determinado ako na baguhin yung buhay nila tulad ng pagbago ko sa buhay ko.

The lack of quality education is one of the causes of poverty: those on the fringes resort to violence because there doesn’t seem to be anything else in the cards for them. Ballon knows his students could be at risk if he doesn’t perform his duties with utmost care; he sees his past self in them and is therefore determined to give them the alternate ending he deserved all those years ago.

In fact, he brags about being able to convince four potential dropouts to persevere through their senior year. “Naaalala ko kasi yung nagawa kong yun. Firsthand ko kasing na-experience yung consequences ng pagkakamali sa buhay, kaya sobrang determinado ako na baguhin yung buhay nila tulad ng pagbago ko sa buhay ko.”

Angelica Galang

Paco, Manila has long been regarded as a drug hotspot, home to an interconnected web of users and pushers. Anyone born into that kind of environment can’t always find an easy way out – Angelica Galang knows this all too well.

Born to a mother who was in and out of jail because of trafficking charges, Angelica spent her teen years participating in the drug trade to support her live-in partner’s addiction, until she also found herself behind bars at only 21 years old.

Upon being sentenced to almost two decades in prison, Galang said she was overwhelmed with a sense of hopelessness. “Ang bata bata ko pa, nandoon na ako, tapos ang haba pa ng sentensiya ko. Ang dami kong kasama na matagal na rin nandoon na hindi pa rin nakakalabas. Anong mangyayari sa buhay namin kapag nakalaya na kami? Ano pang kapupuntahan namin?” She spent many miserable days lying down on the cold concrete floor, with only a 1.5L tub of ice cream as her pillow.

Yung panahon ko sa loob yung nagsilbing wake-up call namin lahat. Pinagpanata ko na sa akin matatapos yung mga naging pagkakamali namin at magiging instrumento ako ng Diyos dito sa labas tulad ng ginawa Niya sa akin sa loob.

When she was transferred to the Correctional Institute for Women, Galang felt like something in her shifted. “Pagpasok ko pa lang, parang may bumulong sakin. Parang may nagsabi na dito na magbabago buhay ko. Sinalubong ako ng mga taong nagppraise and worship, tapos ang bumungad talaga sa akin ay simbahan.” This change in environment pushed her to immerse herself in livelihood programs and Bible study sessions. Her active participation and good conduct made her eligible for parole after only 10 years.

Now, Galang is proudly sober and has managed to convince her loved ones to clean up their act as well: “Yung panahon ko talaga sa loob yung nagsilbing wake-up call namin lahat. Pinagpanata ko na sa akin matatapos yung mga naging pagkakamali natin at magiging instrumento ako ng Diyos dito sa labas tulad ng ginawa Niya sa akin sa loob.”

Most days, she runs her modest merienda business in the city market, which allows her to apply the cooking and entrepreneurship skills she picked up during her time in jail. But no matter how packed her schedule gets, Galang makes it a point to visit those she left behind at the CIW, whom she endearingly calls her “ilaw at gabay.” “Paglabas ko sa kulungan, konti lang yung naniwalang kaya kong magbago. Kahit sinabi kong determinado kami ng pamilya ko na wakasan yung maling gawain namin, marami pa ring nagduda,” she said. “Kaya, grabe yung pasasalamat ko sa mga nakilala ko noong nasa piitan ako.”

It doesn’t matter whether she comes bearing a fancy meal or simple snacks: she knows that the act of remembering and returning to them means more to them than anyone could ever imagine. She plans to set up a permanent stall in the city market and share even bigger blessings during her next visits. For Galang, it only seems fitting to dream for the people who taught her how to dream for herself when she needed it most.

Lora Marie Catap

When Lora Marie Catap shares the trials she has gone through, one would think she no longer believes that a higher power is looking out for her. And yet, she claims that these have only strengthened her resolve to devote her life to God.

Over a decade ago, Catap led a low-profile existence: she and her husband had four kids, a house, two cars, and the financial stability for the occasional splurge. But a long-lost friend reached out to her with an offer to live and work in Japan. “Tayong mga tao, hindi naman talaga tayo nakukuntento sa kung ano meron tayo. We always want more,” she said.

Dazzled by the possibility of a new life, she invested most of their joint savings into the opportunity. “In the process, nagreto din ako ng ibang family members and friends na pwedeng mamasukan na factory worker,” she explained. But just when their dreams were starting to take shape, her contact disappeared with all their hard-earned money, leaving Catap to take the fall.

Being exposed on national news for something she wasn’t even responsible for destroyed her family: her husband, who had no prior knowledge of what she had gotten into, was also arrested for connivance. And as if fate wasn’t already unkind enough, calamity struck her loved ones twice while she was behind bars and the lawyer she trusted stole their remaining belongings. The stress caused Catap to contract a severe stomach illness that almost killed her.

Catap believed the sickness was just a part of the grand plan the Lord was orchestrating for her: “Matagal kong kinapitan yung pangako ng Diyos, na wala Siyang ibibigay na pagsubok na di ko kakayanin, at hindi Niya ako pababayaan kahit ano man mangyari.” True enough, a visiting lawyer took notice of her condition which reminded him of his sister who succumbed to the same illness and offered to go over her papers pro bono, in light of a new law on estafa. Within a couple of weeks, her sentence was modified and she was set free.

Catap found her readiness for the unknown handy in rebuilding the life she left behind. Though she and her husband patched things up and reunited with their children, misfortune befell them once again, forcing her to seek employment as a domestic helper in Saudi Arabia.

Umaasa ako na balang araw, mapapatawad ako ng mga nasaktan kong tao lalo na sa pamilya ko at pamilya ng asawa ko, at matatanggap ulit ako ng malayang lipunan.

It’s easy to assume that Catap’s happy ending seems so unjustly elusive: she does admit to suffering from culture shock and homesickness from time to time. Despite this, Catap can’t ask for anything more. While they aren’t as well-off as they were and they remain miles apart, she now knows that their love is all she needs to conquer the one challenge she has left.

“Umaasa ako na balang araw, mapapatawad ako ng mga nasaktan kong tao lalo na sa pamilya ko at pamilya ng asawa ko, at matatanggap ulit ako ng malayang lipunan.”

If you want to help out in the mission of the Philippine Jesuit Prison Service, whether as a benefactor or a volunteer, feel free to check out and message Philippine Jesuit Prison Service on Facebook or visit their website. For this year’s Prison Awareness Week, PJPS is having a fundraising campaign for the PDLs that you can contribute to here.