500,000? 180,000? Here’s why the math behind crowd-counting can be complicated, and contentious

It has been said that there are three kinds of lies—lies, damned lies, and statistics.

Counting people in a small room seems simple enough. But multiply that number of people exponentially over large areas with irregularities in terrain that also has multiple entrance and exit points and you got yourself quite an equation. Then, factor in a highly charged election season wherein the sum of such an equation yields a significant weight in the narrative of a major political campaign and suddenly what is truth and what is propaganda becomes not so simple anymore.

These are the basic complications when counting crowds during political rallies in this current campaign season.

Recently, two major rallies illustrate how far campaign propaganda has been trying to push the envelope to establish which side has more ground momentum.

During the March 13 UniTeam rally in Las Piñas, the camp of presidential aspirant Bongbong Marcos claimed that 500,000 people showed up. Later on, the police whittled down the initial estimate to a significantly smaller 18,000.

Presidential candidate Leni Robredo's March 20 rally was the camp’s reportedly biggest to date, with the organizers initially estimating a 180,000 crowd turnout, versus the police’s 137,000 estimate.

Muscle-flexing and wagon-jumping

At the risk of belaboring the obvious, the size of a crowd is of great import for each political camp jockeying for pole position in the run-up to the elections.

Campaign strategist Alan German said two campaign concepts are at play with respect to crowd counting, namely "muscle flexing" and "wagon-jumping."

It leverages on the Filipino voter's predilection for choosing who is trendy.

"Muscle-flexing is mainly about optics," German told PhilSTAR L!fe.

German said the the appearance of growing public support may help spur further momentum by creating new political alliances “as many politicians may see that the votes they need are also within that crowd.”

On the other hand, "Wagon-jumping", German said, “leverages on the Filipino voter's predilection for choosing who is ‘uso/ trendy’, or who appears to be the popular candidate at any given moment.”

“Massive rallies create this perception, and thus encourage what we call ‘soft’ or ‘non-tenacious' voters to come on board,” said German.

UP Diliman political science associate professor Dr. Jean Encinas Franco likewise also said that the size of crowds at rallies also show to what extent a candidate has figured out the Filipino voter.

"To a certain extent, it demonstrates that those in the rally are not just going to vote but will convince others to vote for their candidate. Attendance at rallies signifies that the candidate and what he or she represents, have captured the attendees' imagination," she said. "Provided of course that those who attended voluntarily went to the rallies."

So how does one really go about estimating swarms of people?

Jacobs' method

The most well-known way to estimate the size of a crowd is through the Jacobs' Method, popularized by journalist Herbert Jacobs. He came up with the technique while observing Vietnam War protests outside his office window in the 1960s.

This method involves dividing an area occupied by a crowd, a stadium for instance, into sections.

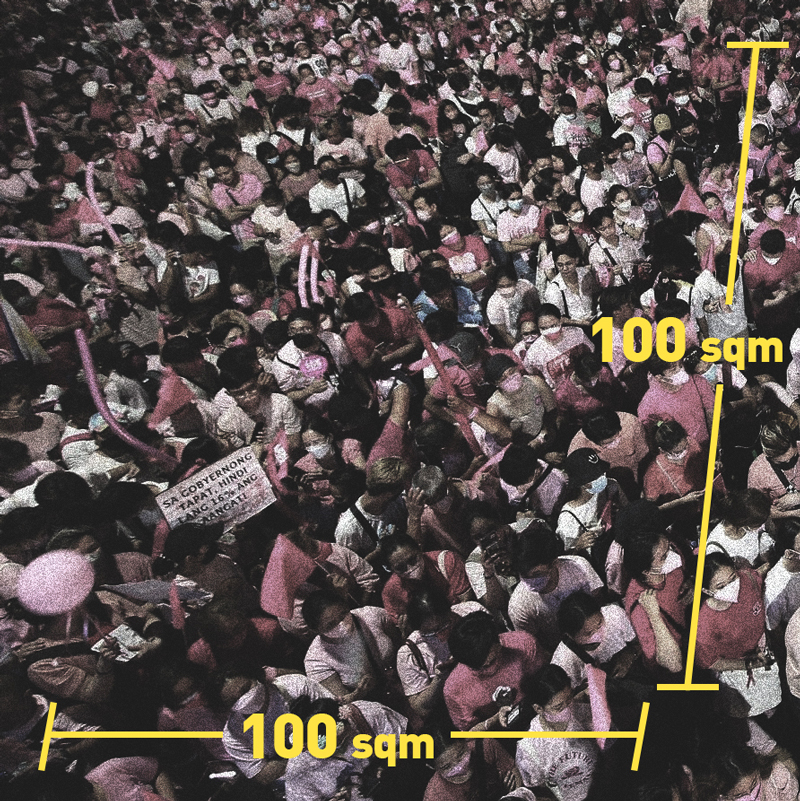

Once you've separated a section of the crowd, the next thing to determine is the density of people in that space. To do that, you have to find the average square meter each person in the crowd takes up. For instance, in a packed crowd like in the photo above, that's an average 1/2 square meter occupied by a person.

Let's say the chunk you're looking at measures 100 sqm. We then divide 100 sqm by 1/2 sqm (the average space a person takes up) to find the density. Looking at the photo above and doing the math, that's roughly 200 people in one 100 sqm section.

The next step would be to multiply the density, in this case, 200 by the number of sections with people in it.

This method also forms part of the math behind some online crowd-mapping tools.

The Philippine National Police (PNP) in a way also uses the Jacobs' method. Manila Police District spokesperson Major Philipp Ines said their baseline assumption is that five persons could fit in one square meter in a highly packed crowd.

"Ang pag-estimate sa crowd, ang ginagamit natin per metro kwadrado. Halimbawa sa isang field, gano ba kalaki ang sukat, ang isang metro kwadrado kasi yun talaga hindi na makagalaw, limang tao yan," Ines said.

"Kung medyo nakakagalaw ang crowd, apat yan sa metro kwadrado, kung medyo mas maluwag pa, so tatlo lang, ganun ang pag estimate yan."

He added that the PNP usually measures crowds with the help of technology. "May satellite maps naman para hindi na mano-mano, titingnan na lang."

For the PNP, knowing the actual size of a big rally is important as this figure usually corresponds to the scale of their ground deployment.

"Kailangan natin i-base yung bilang ng pulis natin sa crowd. Usually ang standard is one police is to 500, pero depende pa rin sa klase ng rally," Ines said.

Margin of error

However, University of the Philippines Los Baños mathematics professor Dr. Jomar Rabajante said that this method—although simple—has a wide margin of error.

"The assumption made in this simple method is highly sensitive to the assumption kung ilang tao ang nandoon sa square meter," he said. "Sobrang sensitive ng result sa naging assumption."

"Hindi talaga magtutugma yung reports kasi yung isa siguro inassume 1x1 isang tao, tapos yung isa inassume 1x1 dalawang tao. Depende sa assumption," the professor added.

Multiply the difference in assumption per square meter and the margin of difference, or error, likewise increases exponentially.

Veteran journalist Gerry Lirio said that the character of people attending a rally is also a factor that influences the traditional computation.

Skepticism should be the professional standard.

"Yung crowd ni Leni parang Mardi Gras. It's very festive kasi may mga kumakanta at sumasayaw so that could mean na mas may onting espasyo on the ground," said Lirio. "The aerial shot could give a perspective but it can not of course give you the detail on the ground."

Neural networks

Rabajante said a more accurate measure compared to the traditional method is the development of a "neural network" that could determine crowd density through a machine learning algorithm.

"Para siyang artificial brain mimicking how our brain works but in a computer," Rabajante said.

The algorithm could be trained and tested on a range of ways on how best to determine the number of people in an area through density maps.

"There are advancements already (in computer science) that could estimate these numbers," he said.

For now, Rabajante said that crowd estimates could also be given in a range instead of one figure.

"Siguro kung yung simple method parin yung gagamitin, maglagay sila ng range depending on the assumption," he said. "Kung talagang malaki yung range, explain why."

Skepticism

With these complications, Luis Teodoro, board trustee of the Center for Media Freedom and Responsibility, said that journalists reporting on rallies should maintain a dose of skepticism when served with data regarding crowd estimates.

"Dapat mayron kang kaunting skepticism lalo pag nanggagaling yung info sa isang source na hindi disinterested, like sa camp ng mismong politician," said Teodoro.

"Dapat skeptical ang reporter, yun ang dapat professional standard."

For a public likewise inundated with differing information, or even outright disinformation, from various camps, a healthy dose of skepticism also wouldn't hurt in trying to tease out the truth from the complicated equation of the current elections.