When we watch 'Pinoy Big Brother,' we’re really watching ourselves

Every week, PhilSTAR L!fe explores issues and topics from the perspectives of different age groups, encouraging healthy but meaningful conversations on why they matter. This is Generations by our Gen Z columnist Angel Martinez.

A little TV lesson for those who aren’t aware: Pinoy Big Brother, the show, was lifted from Big Brother, the figurehead of a totalitarian regime from George Orwell’s 1984. Through grueling weekly tasks and competition as well as mandatory evictions, housemates are at the mercy of their own omnipresent leader who thrives on oppression and control. It’s a test of wits, meant to push ordinary people to their very limit.

Despite these sinister themes, isn’t it fascinating that we don’t just tolerate but celebrate seeing them on our screens?

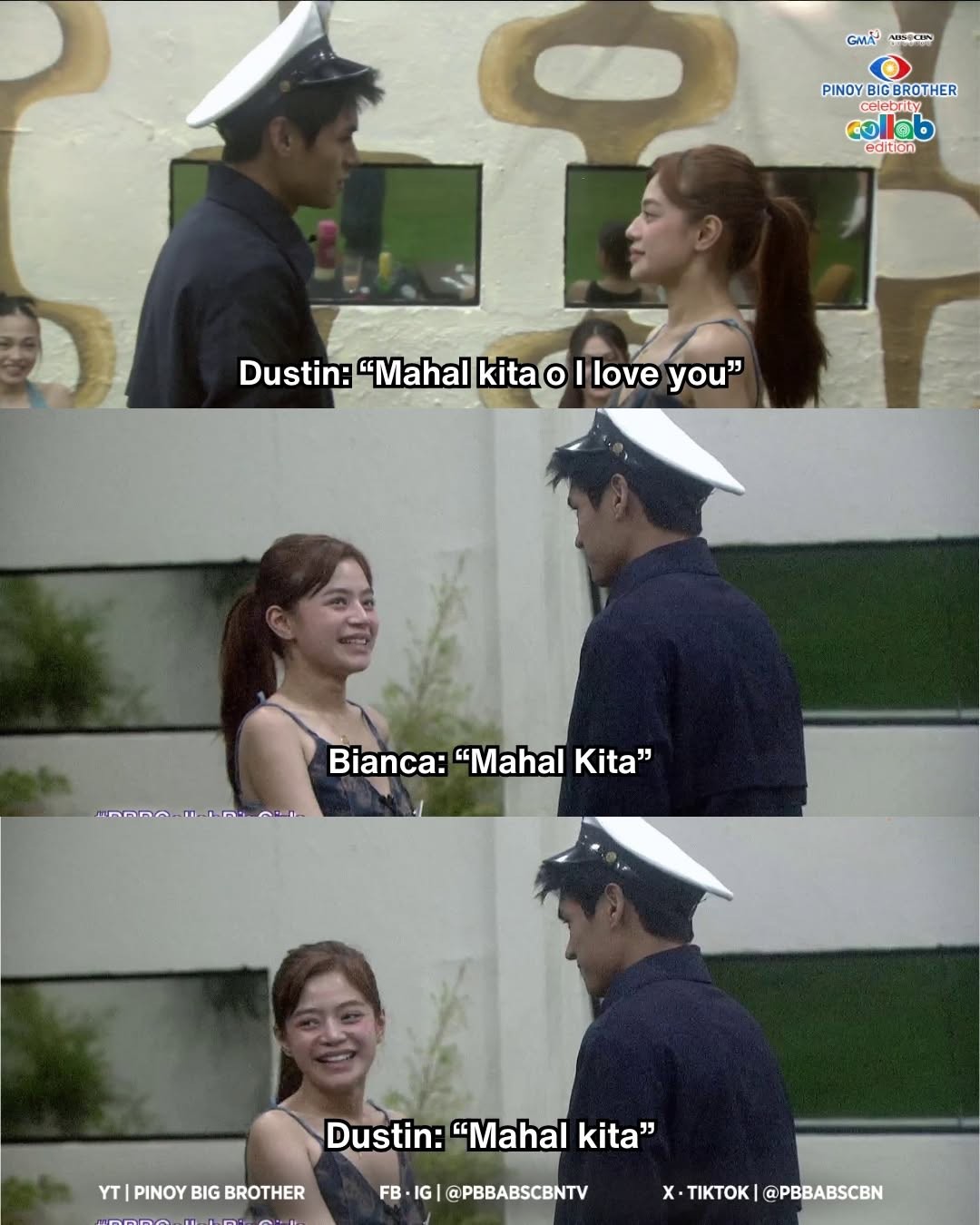

Since its launch last March 2025, Pinoy Big Brother: Celebrity Collab Edition has dominated internet feeds: from Will Ashley and Bianca de Vera’s will-they-won’t-they situation (and Dustin Yu’s interference) to River Joseph and Ralph de Leon’s golden retriever and "saing king" cuteness. Full episodes and livestream links rake in impressive viewership numbers, and housemate names are all over the trending topic list—even if reality TV has been seen by some as mindless fluff.

It would be a cop-out to attribute this season’s success to the celebrity contestants alone. Sure, they’re easy on the eyes, with a certain level of name recall (or notoriety, depending on who we’re talking about). But Nino Leviste, associate professor of sociology at Ateneo de Manila University, believes there might be more to it. “Reality shows like PBB appeal to Gen Z because they mirror how this generation lives—always online, always watching and being watched,” he tells PhilSTAR L!fe. “Since they’ve grown accustomed to curated lives and constant oversharing, observing strangers in a house feels familiar.”

PBB, however, functions as a large-scale social experiment, placing these fallible human beings in a high-pressure environment. “Somehow, we are made to believe that what we see is, indeed, real, and it is part of our viewing investment,” Louie Jon Sanchez, associate professor of broadcast communication at University of the Philippines Diliman, shares with L!fe.

We want to be entertained, so we suspend our disbelief and wonder: When stripped of all layers of artifice, who are these public figures, really? Who will crack under stress, and who will stand up for their beliefs? The latter is a common thread that ties most past Big Winners together, like "Commander" Nene Tamayo from Season 1 who bravely stood up to Kuya’s manipulative orders and Season 2’s Beatriz Saw, best known for ingraining in us that respect is earned, not imposed.

More importantly, the show serves as an interesting character study: proof that humanity exists on a spectrum and that everyone is capable of both redemption and failure. For instance, Mika Salamanca—aptly called the “Controversial Ca-Babe-Len ng Pampanga”—was arrested in Hawaii for violating quarantine mandates and is now determined to rewrite her own destiny.

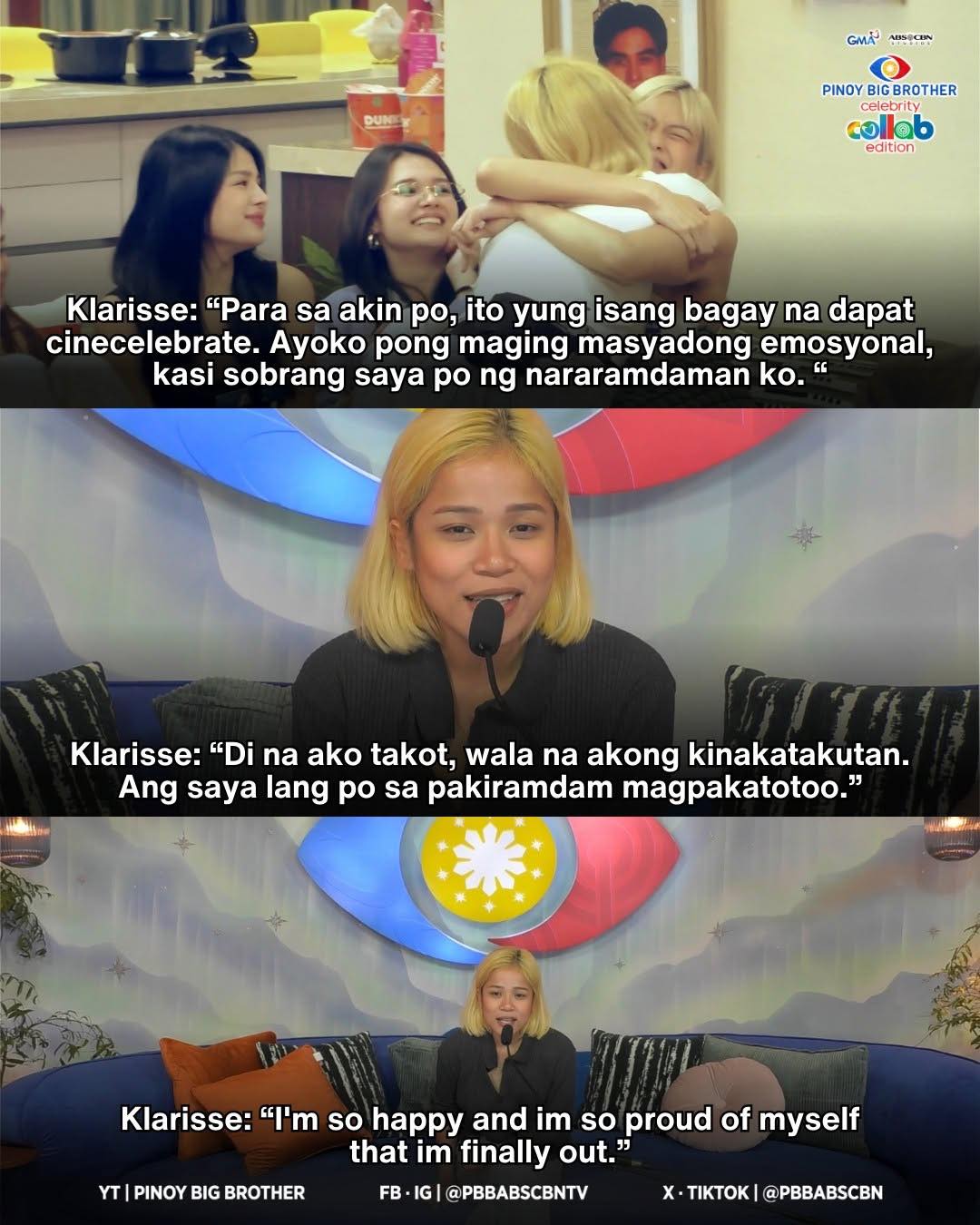

As these participants explore their identity free of external factors, viewers can’t help but latch onto resonant aspects of their personality. I’m sure many could relate to Esnyr Ranollo’s heartfelt confession of his rift with his father, or Klarisse de Guzman’s newfound freedom as a member of the LGBTQIA+ community.

Events that transpire throughout the season are also markers for our own morality: What does it say about us that Brent Manalo’s wallflower nature makes us uncomfortable? Why do we want AZ Martinez evicted just for having crushes on her fellow boarders? Similar to what Taylor Swift laments in her hit The Man, why do we label the guys as “strategic” and “calculated,”,while accusing women of being inauthentic backstabbers when they’re both just gaming the system?

We not only glean what we desire and despise, but also use these to determine what happens next. According to Leviste, Pinoy Big Brother is more than the drama: “It’s the feeling of being part of the story. Through voting, social media reactions, and confessionals, Gen Z isn’t just watching—they’re shaping the outcome. It’s active, not passive.”

However, this isn’t always empowering in nature: Audiences were quick to evict “problematic” and “narcissistic” AC Bonifacio after airing others’ dirty laundry and maligning the reputation of her own duo-mate, Ashley Ortega. While such behavior shouldn’t be tolerated, it’s worth remembering that what we watch can so easily be spliced and sewn back together to fashion new narratives. “Getting too invested might see us mistaking performance for real life, forming strong opinions on people we don’t actually know,” Leviste warns. “It could lead to quick judgments, hate, or cancel culture, and encourages us to turn serious struggles into a form of entertainment.”

Reality TV has always relied on the highs and lows of its contestants for ratings, sometimes even with the element of the online witch hunt ensuring that their misfortunes will endure. As Sanchez puts it: “We have a blurred sense of reality nowadays, and truthfulness and authenticity have become relative.” Even if we must demand better from shows and ourselves, we have to admit: We are entertained by the mess. It gives us something to gawk and talk about. Most importantly, it shows us that maybe the mess we have in our own lives is something we can make sense of after all.

Generations by Angel Martinez appears weekly at PhilSTAR L!fe.