Pampanga: A historical culinary powerhouse

The “Kapampangan Nation” is abuzz. A Culinary Heritage Council was organized, however hurriedly and informally, currently holding a consultative townhall meeting at the Pampanga Provincial Capitol in San Fernando as of this writing. The issue at hand is the recent announcement of President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. vetoing a proposal declaring Pampanga as the country’s Culinary Capital, saying it may cause “discrimination, loss of diversity and regional bias.”

It must be recalled that Senate Bill No. 2797, declaring Pampanga as the “Culinary Capital of the Philippines,” sailed smoothly through the legislative process on Dec. 9, 2024, and House Bill No. 10634 was adopted by the House on Aug. 7, 2024; only to be vetoed by Marcos on March 12, 2025.

Though the Kapampangans’ euphoria may have turned abruptly into disappointment, the veto came as no surprise for this writer.

Some six months ago, I was invited by the Provincial Board to join Robby Tantingco, director of the Center for Kapampangan Studies (Holy Angel University, Angeles City), to join the research team, working together with other kabalen cultural workers and journalists.

After several meetings, Robby and I were of the same opinion—we do not need legislation to be officially called the “Culinary Capital” of the country. We already are considered as such. Google any search engine about Pampanga, 99.99% will come out Pampanga being known as the Culinary Capital of the Philippines. And that’s that. Period. In fact, Robby recommended other less-contentious titles such as “Culinary Heartland” as described by Conde Nast Traveler.

To boot: “For the uninitiated, Filipino cuisine is best characterized by its signature trifecta of flavors: sweet, salty, and sour. North of Manila, Pampanga is referred to as the culinary heartland of the Philippines, offering unrivaled food experiences that marry indigenous cooking techniques and foreign influences. Pampanga is the birthplace of some of the most delectable Filipino dishes, from the classic sisig (sizzling chopped pig’s head) to bringhe (a savory sticky rice dish with coconut milk). The Kapampangan people’s devotion to their cuisine is evident on every street corner, with the scent of grilled meats and the clanking of pots and pans filling the air. Visit during the annual week-long Pampanga Food Festival held every April."

Speaking of being mentioned in the Conde Nast article, in May 2016, I was invited by then Ambassador Jose Cuisia Jr. to compete in the Embassy Chef Challenge in Washington, DC. I was to prepare a single dish to represent the Philippines, to serve to 1,000 paying guests (who were the judges), using Filipino ingredients available in the US. A tall order, I must say, but not impossible.

Long story short—I won the People’s Choice Award over 26 other contestants. The Philippine flag flew high that evening, albeit a digital projection on the stage wall.

Mr. President, your reason that such a bill “may cause negative cultural implications, discrimination, regional bias and loss of diversity” is flawed. Each region has its own character, assets and attractions. They are not created equal. Pampanga may not have rice terraces, white sand beaches, heritage sites, but local and foreign tourists flock to our province for our food, regardless of such a bill.

In the early 1980s, my eldest brother Lito, who was already residing in Makati at that time, would bring his bosom friend the late Bong Daza, wife Gloria Diaz, brother Sandy Daza, and Babes Romualdez [now PH ambassador to the US], to have Aling Lucing’s sisig at the railroad tracks of our city Angeles. Back then, sizzling sisig was only known to us Angeleños and to the accidental tourists. It remained known as the Angeles sisig for many years, not even in nearby Pampanga towns that still were serving the traditional wet sisig babi or boiled pig’s head, cut into strips and served with vinegar, onions, chili, salt and pepper. This is exactly the same as the Tagalogs’ kilawin na baboy, and the Ilocano dinakdakan, then with the addition of pig’s brain and not mayonnaise nowadays. It’s just an accident of history that the former rose to international stardom and latter lost in history.)

.)

Speaking of ”Pampanga Nation,“ this refers to not just the Pampango-speaking people of Pampanga, but also the Kapampangan towns of Bamban, Capas, Concepcion, San José, Gerona, La Paz, Victoria and Tarlac City in Tarlac province; Cabiao, San Antonio, San Isidro, Gapan, and Cabanatuan in Nueva Ecija; San Miguel de Mayumu, Baliuag, San Ildelfonso, Hagonoy, Plaridel, Pulilan and Calumpit in Bulacan; and Dinalupihan, Hermosa and Orani in Bataan. And all the Kapampangan diaspora scattered around the world.

In the 1972 publication The Pampangans, American historian John A. Larkin (The Regents of the University of California) wrote on the regional uniqueness of the Kapampangan people and its cuisine, its land, and its contribution to nation building. He clarified the various terms: Pampanga as the name of the province, Pampangans (English term) as its people, Capampangan/Kapampangan as the language.

In Larkin’s timeline of the history of the province, which he based mainly on Blair & Robertson’s The Philippine Islands, a 55-volume consisting of primary-source documents for Philippine history translated into English, he highlighted:

1565—Arrival of Miguel López de Legazpi and friar Andrés de Urdaneta from Acapulco, founding the first Spanish settlement and Roman Catholic mission in Cebu.

1571 May 19—founding of the fortress city of Intramuros by Miguel López de Legazpi, making Manila the capital of the new colony.

1571 December 11 (7 months after the founding of Manila)—the establishment of La Pampanga by Martin de Goiti. They called the region “La Pampanga,” a reference to its inhabitants as “the people by the riverbank.” It is the oldest among the seven provinces of Central Luzon and its borders originally encompassed parts of Bulacan, Nueva Ecija, Tarlac, Bataan and Quezon. La Pampanga comprised all of which stretches north to Lingayen Gulf, west to the Zambales Range, south to Manila Bay, and east to the Sierra Madre Range. (Larkin, pp. 24-25)

1598—Governor General de Sande wrote: “The province which in all this island of Luzon produces the most grain is that called Pampanga…. This city (Manila) and all this region is provided with food—namely rice, which is the bread here, by this province; so that if the rice harvest should fail there, there would be no place where it could be obtained (emphasis added).” (De Sande, “Official Report,” p.80. See also, “Ordinance of the Royal Audiencia, December 7, 1598,” B&R, X, 307-309.)

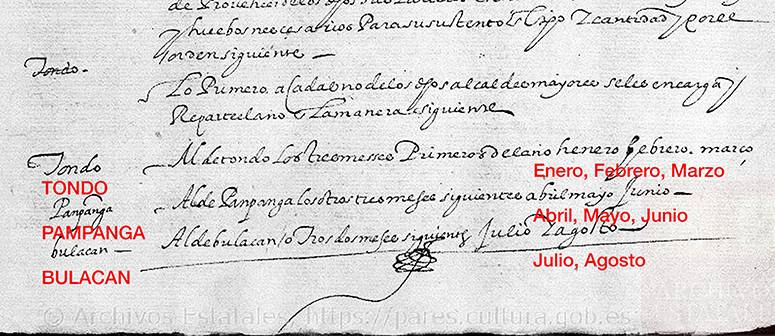

It was this same tribute (taxes in kind) that the Pampango historian Mariano A. Henson wrote in his book Ways of a Pampango Gentleman published in 1959. He wrote: “Not long after the Spaniards conquered Luzon in 1571, on December 7, 1598, Pampangos were ordered by the Audiencia (Supreme Court) to provide the city of Manila with a weekly supply of fowls, eggs and swine during three months...” Reading Mr. Henson’s article, I kept wondering why the decree’s duration was only for “three months”?

Felice Sta. Maria answered my query. The same decree was mentioned in her book The Governor-General’s Kitchen (Anvil Publishing, 2006). She wrote on page 66: “Additional action was taken on December 7, 1598 when adjacent areas were scheduled to supply the crown. Tondo began the year through March (it must be noted that Tondo was a Kapampangan colony during that period), followed by Pampanga into June, Bulacan during July and August, Laguna in September and October, with Mindoro and Balayan feeding the last two months. Each supplier delivered weekly to a designated city official: 300 laying hens (the third or fourth parts pullets, at the rate of four small ones or two large ones for every laying fowl); 2,000 eggs; the number of swine ‘that he may consider proper, and that can be produced.’ (Emphasis added)

I have to note that, up to this point, my sources had been only secondary and tertiary sources. I was resolved to get to the bottom of this “holy grail.”

On Feb. 14-22, 2024, I was in Sevilla and Cadiz, Spain, upon the invitation of the Spanish Tourism Board. I was on a quest for bacalao dishes, with Sevilla being the mecca of bacalao during the cuaresma, arriving Sevilla on Feb. 14 on Ash Wednesday.

While there, I met Dr. Antonio Sánchez de Mora, main archivist and historian, in his office at the Archivo General de Indias. We had met in Manila in 2016 during the Madrid Fusion Manila where he was one of the guest speakers talking about the flavors that crossed the oceans during the Manila-Acapulco Galleon Trade.

Don Antonio and I actually set up a lunch date, him treating me to a round of tapas in exchange for my adobo book I’d sent him the previous year. Around two weeks prior my arrival, I’ve messaged him of my intention to research for the primary source of the Ordinance of the Royal Audiencia, dated Dec. 7, 1598, mentioned above in The Pampangans by John Larkin.

He confessed he was a bit wary whenever he sees the B&R footnoting, so he made it his personal mission to find the primary source. Long story short, after hours on the Archivos’ computer, we hit a blank wall. I left Sevilla empty-handed, save for the memorable tapeo of bacalao, bacalao, and more bacalao dishes he made me try.

Anyway, when I finally got home in Pampanga, I received several messages from Don Antonio. He found the “holy grail”—the original hand-written decrees pertaining to the Dec. 7, 1598 ordinance.

“I found the document you’re looking for. They are copies of orders of the judges and officials of the Royal Audiencia of Manila. Very interesting the use of word ‘baboy’ instead of Spanish ‘cerdo.’ You have also to read the previous one, both translated and published by Blair & Robertson, X, pp.304-310. Felice has to read them also.”

Forwarding the message to Felice, she replied: “The manuscripts need to be transcribed, then translated into Spanish/English. Hagiography is a specialization.”

First modern mention of Pampanga as ‘Culinary capital’

“Pampangan cooking,” wrote Larkin in 1972, “differed noticeably from that of other groups in the Philippines. The Pampangans, although using the same basic meats and vegetables, tended to prepare spicier dishes, such as curries, which were foreign to the taste of most Christian Filipinos. Generally speaking, Pampangans produced more exotic, imaginative and fancy foods, including a wide variety of pastries and confections that set them apart from their neighbors. One could certainly speak of a distinctive Pampangan cuisine.” (Emphasis added)

In 1990, Felice Sta. Maria wrote an article in Mabuhay, PAL’s inflight magazine, about Pampanga’s dining scene. It was titled “Gourmet Highways.” She concluded her article thus: “Culinary historians have ventured one hypothesis after another without unquestionable success to explain the singularity of the Gourmet Province. Whatever the cause, an ancient kingdom of warriors and masters of irrigation turned Pampanga, the land of rivers, into the Philippines’ culinary capital.” (Mabuhay magazine, Feb. 1990, p.19)

I asked her if she may have been the first to call Pampanga as such. She replied: “I was not aware. It was literary license. But a writer’s gushing does not mean ‘gourmet capital’ should be a government-given label. It was a personal opinion. It has too many repercussions if government-given. For writers to say that in an article is fine. But not the government.”

1992—Gilda Cordero Fernando, in her book Philippine Food and Life (Anvil Publishing, 1992) described Pampanga as “The Gourmet Province.” She wrote: “Food became a cult in Pampanga as well because of the Spanish friars who enjoyed a comfortable life from the religious fees and revenues of Spanish fields.” (Tributes first mentioned in 1598). “They were forever being gifted with eggs, chickens and viands by the old maids and pious housewives who looked after the church.”

We have an expression in Pampango: “Ing pari, ya ing Ari” (The priest is King). They also had a “pick” of the prettiest of barrio lasses, with parents feeling “privileged” having their daughter serving the household of the parish priest, with privileges (wink, wink). But I’m digressing.

“Le Gironiere was full of accounts of priests who entertained him the best of tables. Victorina Ocampo of San Fernando learned the rudiments of pitisus (cream puffs, brazos, ensaimadas) from the Spanish cook of the archbishop.”

1993—In the book Cocina Sulipeña by Gene Gonzalez, his uncle Bro. Andrew Gonzalez wrote in the introduction: “The preoccupation with the proper preparation of food perhaps explains why Kapampangan cooking has become nationally famous for its quality and flavor. A confluence of affluence—the wherewithal to indulge one’s palate; and influences, both Hispanic, European and Chinese, mixed with the Malay culture— made it possible for the settlements along the Rio Grande de Pampanga to have access to the best ingredients not only in Asia but also in Europe.”

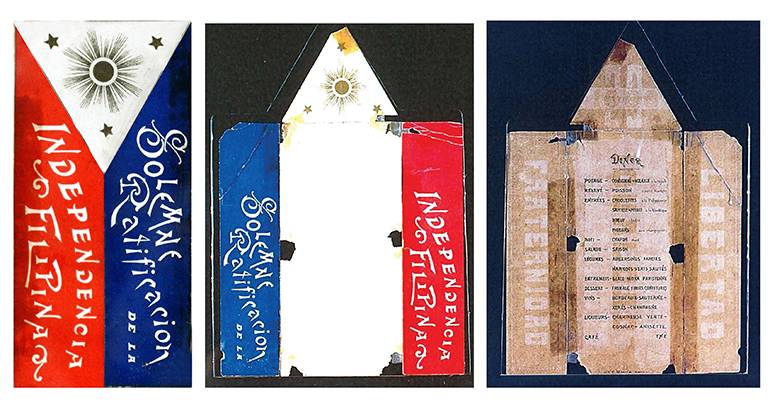

Chef Gene also noted in his book it was the cooks from Sulipan, Pampanga, who prepared the meals at the Malolos Congress in Barasoain, Malolos, Bulacan in 1898.

Culinary quilt

Since the announcement of the veto came out, I’ve received several text messages asking what my opinion is on the President’s veto of the Culinary Capital bill. This is my categorical reply: That is his presidential prerogative. Whatever my opinion is, or anybody else’s for that matter, will not really matter in the broader scheme of things. I’m not familiar with parliamentary procedures, but is the presidential veto even appealable? Otherwise, it’ll be all a waste of time and energy fighting “city hall.”

I wrote the following in my column in The STAR on April 6, 2017 during the Madrid Fusion Manila. It basically echoes what Marcos wrote explaining his veto:

“Unity in diversity—regional lunches—The emergence of chef and/or regional-centered Filipino restaurants is a clear proof that the Filipino diner has come of age. He goes out with an open mind and palate. There has been a rediscovery, renaissance if you will, and appreciation of the diversity of our culture and cuisines.” (Emphasis added)

In another column: “The phenomenal rise in popularity of the Ilocano bagnet Pampango sisig, or Bacolod’s chicken inasal in the national culinary scene is a good illustration of how the best, or at least the most popular of a regional cuisine actually takes part in weaving the quilt that makes up Filipino cuisine as a cohesive whole.”

Is it a coincidence that the former DOT’s “It’s More Fun in the Philippines” logo has the Philippine map woven like our tightly knit banig (straw mat), with its multi-colored mosaic representing the different regions/cultures that make up our nation?

Nonetheless, whatever the final outcome is, in most people’s minds, or should I hasten to add, appetites/stomachs, Pampanga IS the culinary destination to beat.

A matter of taste (buds)

I’m often asked what my second favorite regional cuisine is (the first, of course, is Pampanga, being my home province). My reply is always a non-committal “Depends on my mood at the moment.” And if I’m pressed for an answer, lest I be misquoted, I say “In their own way, they’re all equally good.”

Doing our “field” research writing the Linamnam book published in 2011, my darleng Mary Ann and I scoured the archipelago for grub on what the locals eat. We would stay 3-5 days in each locality/town/province, depending on the “food culture” of the place. But in every place, one could only eat so much of “their” food until we would always pine for home cooking after a day or two.

Okay, okay. Admittedly, I would name Ilocano cuisine as my second peyborit—all because of bagnet, I must hasten to add. It’s not quite the lechon kawali we’re all familiar with (with the crispy skin a hit-and-miss thing.) It’s like having a super-crunchy chicharon with a moist meat attached to it. It is usually served with KBL—Kamatis (tomatoes), Bagoong isda (fish paste), Lasuna (shallots)—not to be confused with the Kilusan Bagong Lipunan spearheaded by Imee Marcos, then in her early 20s, during the early years of martial law.

Anyway, in the 25 years Mary Ann and I have been married, we must have traveled to the Ilocos region at least 10 times. Just the thought of having Batac’s famous empanada, bagnet and longganisa, or the bagbagis (crispy pig’s intestines) at Preciosa’s is enough to get us to pack and trek all the way to the north, again and again. Just last year, we drove to Vigan for the Holy Week. I also have written a good number of articles on Ilocos cuisine, as well as Ilonggo, Negrense, Cagayan de Oro, Davao City, etc. Nobody could accuse me of favoring my own. I’ve been “nationalistic” in my writings, and never favoring one region.

Pampanga vs Ilocos mindset

In one of those trips to Ilocos, Irene Marcos Araneta introduced us to Dawang’s crispy dinardaraan (dinuguan or blood stew with tidbits of crispy chicharon thrown in), as well as Batac’s coiled longganisa, to save on the string, she said in jest. She also warned us that contrary to popular belief, Ilocano diet is quite unhealthy due to its high sodium and fat content.

Though Irene may have said it in jest, the Ilocanos’ frugality and strict adherence to tradition are quite well-known beyond their borders.

Sometime in 2009, Irene invited Glenda Barretto and I to curate a dinner for The Governor’s Ball, a fund-raising tradition in Ilocos Norte for the benefit of Gameng Foundation that operates Museo Ilocos Norte. It was hosted by then Governor Michael Marcos Keon at the Ilocos Norte Hotel and Convention Center.

The menu Tita Glenda and I curated consisted of an appetizer of crostinis made from Pasuquin biscochos with various toppings, a fresh salad, soup, risotto and dessert. There was imaginative use of local ingredients, highlighting the crisp freshness of vegetables in the salad and soup, and the possibilities of the Ilocano dish pinakbet as an Italianate risotto. The dessert mixed fresh mango balls and fried saba (plantain bananas) with rice confections (tinupig, bilo-bilo) in a skewer, on a bed of sapin-sapin drizzled with a coconut crème caramel sauce.

Our objective for the innovative menu was to show how local tastes and flavors can be interpreted and presented in a different way, and hopefully inspire local cooks to take a fresh look and create their own versions of Ilocano dishes.

Instead, we have caused quite a stir—a spirited debate among the all-Ilocano guests ensued, to put it mildly, especially with the fiercely loyal Ilocano purists. One could hear the murmur among the guests getting louder every time a new dish was served. Could they have been inciting a walkout protest, or perhaps plotting to execute Tita Glenda and I, similar to the fate of the perpetrators of the Basi Revolt in 1807? Overheard: “Oh my God, they’re serving us raw vegetables!” (Disclosure: Though Tita Glenda and I weren’t actually present during the dinner, a somewhat humorous post-mortem report was made by an “insider-mole” seated at the governor’s table. Who? Secret!)

Then-Congressman Bongbong Marcos and sister Irene came to the rescue. Marcos ate with gusto double servings of the salad of young sigarillas (winged beans) and katuray flowers with honey-mansi vinaigrette, as well as the crostinis topped with kesong puti made from carabao’s milk from Batac, dinardaraan and higado (liver stew); while Irene loved the low-salt minestrone “dinengdeng” for being a healthy option. Their Ilonggo-descent spouses, Liza Araneta and Greggy Araneta, while not as accustomed to the Ilocano dishes, loved the sweet desserts. I am not surprised that there has been an Ilocano chef that has risen to national prominence.

Speaking of my peyborit bagnet, back in November 2009, business partners RJ Ledesma and Anton Diaz founded Mercato Centrale, an upscale weekend food market at an open space near Serendra, BGC. Anton offered me a booth, suggesting I serve something new. I came up with Pan de Bagnet, a take on the Italian porchetta (pronounced “por-ke-ta”), roast pork with its crackling served on Italian crusty bread.

Adapting it to local panlasa (tastebuds), I basically served the Ilocano bagnet with KBL salad on toasted ciabatta bread (made-to-order from JohnLu Kua of Frenchbaker chain). One can also liken it to the American BLT sandwich in principle—substitute the bacon with bagnet, lettuce with fresh mustasa (mustard leaves, giving it a somewhat bitter aftertaste similar to arugula), and tomato. Instead of the usual ketchup and mayo, I concocted my own dressing using bagoong isda (fish paste), sukang Iloko (cane vinegar infused with samak or tanbark), cold-pressed coconut oil, and other “secret” ingredients.

It was an instant hit, to say the least, having the longest queues in the six months we were there. Imee Marcos, who was a regular costumer, was overheard saying (pulling her hair, I imagine): “Uki nana, why did it take a Kapampangan Claude Tayag to reinvent our bagnet!!!”—which I took as a great compliment.

A Kapampangan mindset works thus: presented with a recipe or dish, his regional thinking will tell him: “Hmm, papaano ko pa mapapasarap lalo ito? How can I make this more delicious?” given all the ingredients available around him.

I must note again the presence of Clark Air Base for 90 years in our province, and its attendant black market of PX/post exchange goods— thanks to which, during martial law bans on importation of luxury goods, Manileños would drive all the way to Nepo and Dau to buy PX goods and local delicacies.

Our mother was using Brun butter to bake her ensaimadas, uses Marca El Rey chorizos to cook Spanish dishes as well as menudo and picadillo, in lieu of red hotdogs.

An Ilocano cook, on the other hand, might have an inner voice dictating thus: “Hmm, papaano kaya ako makakatipid nito? How can I save on this?”—scrimping on ingredients, unmindful of the quality downturn. His frugality knows no bounds.

Kill bill

Pardon my French, or should I say Ilocano. Non-Pampangos find us Kapampangans as naturally mayabang—boastful, proud, vain. If I may add to what Brother Andrew Gonzalez meant by “confluence of affluence,” it was also the industry of my kabalens and the fertility of the land that truly earned our position in Philippine society. We’ve earned every ounce of it—meron kaming K (karapatan). Bill or no bill.