Something old, something new… in Bacolod

The last time I was in Bacolod, I was in grade school. It was my first airplane ride, with my dad, and I remember being so thrilled with the in-flight meal. In hindsight, it was a pretty naïve impression. Bacolod itself, in my memory, felt provincial, quiet in a pleasant, not eerie way, the sort of place that may be described as “laidback.”

Returning as an adult, I still found the local beat much slower than Imperial Manila, but many things had definitely changed. Bacolod today hums with activity, complete with familiar traffic jams and unruly drivers, except that certain business establishments close shop early. Even the cansi house refused customers by 7 p.m., although it could be simply because they ran out of bulalo due to the whole-rainy-day influx of diners.

Even if the pace has quickened a bit, the people have remained famously warm, with a melodious, singsong way of speaking that makes even small talk sound like an invitation to linger, to sit down, to share something sweet. I prefer the Tagalog term: malambing.

“Smile! You’re in Bacolod!” goes the slogan, but smiles aren’t just for tourists craving inasal, batchoy or piaya; it’s how the locals face life. And like a bride on her wedding day, the city wears something old and something new, blending heritage and modernity into a cultural ensemble that’s uniquely its own.

That’s Bacolod’s magic: a city that honors its past without being trapped by it.

Take The Ruins in Talisay. Unrelated to Café by the Ruins of Baguio hipster lore, or the Parañaque haunt once infamous for pirated CDs and DVDs, this Ruins is the skeletal remains of a mansion built in the early 1900s by sugar baron Don Mariano Ledesma Lacson for his wife Maria Braga.

The mansion was intentionally burned during World War II to prevent it from being used as a garrison by the Japanese Imperial forces. Despite the destruction of mostly wooden components, the Romanesque structure endures. Arches rise from the grass, columns catch the last light of the day, and when illuminated at night, the house looks less like a ruin and more like a dream in stone. Fittingly nicknamed the “Taj Mahal of Negros,” it’s now one of the most photographed spots in the island, the setting of many posh weddings.

We had hoped to tour Victorias Milling Company, Asia’s largest sugar mill, but repairs cut our plans short. Consolation came in the form of pork empanadas from Lola Emma, at the Soledad and Maria Montelibano Lacson Ancestral House, followed by a stroll through the Silay Heritage District. If Bacolod is the City of Smiles, Silay is its sepia-toned memory bank. Dozens of ancestral homes line the streets, evoking images of Intramuros or Vigan, with the aroma of sugarcane wafting in the air.

Among around 300 old homes in Silay, only three are open to the public, and one of them – Balay Negrense or the Victor Fernandez Gaston Ancestral House–is even undergoing a much-needed facelift. We still managed to tour the other two.

The Bernardino-Ysabel Jalandoni House, built in 1908, whispers of a time when sugar fortunes shaped lifestyles. With its carriage entrance, steel-lined wooden iceboxes, a 1910 battery-operated telephone (only for business calls, we were informed, not for chatting), and a “modern” outhouse (palikuran).

Then there’s the Hofileña Ancestral House, a 1930s residence turned gallery, where rare works of Luna, Amorsolo and Manansala hang alongside family heirlooms. Our guide was Rene Hofileña, a former dancer whose light demeanor and gentle pride in his lineage and his city reminded us that Silay’s memory lives on in the people who continue to tell its stories.

Even our lunch stop came with history. Stephen’s at Balay Puti, once the mansion of Adela Locsin Ledesma, used to host the most glittering parties of Silay’s heyday. Now repurposed into a fine-dining restaurant, it serves guests under the shadow of the past and the wealth it exuded.

To balance our lowland experience, we drove up to Don Salvador Benedicto, Negros’ “Little Baguio,” which to me felt closer to Tagaytay with its roadside eateries and lush vistas. We stopped at Kusinata, a restaurant with its own cultural story tied to Negros’ indigenous peoples, where the cool breeze and the distant whisper of a waterfall could easily lull one to sleep, especially after a satisfying meal.

And then, from the old, we moved to the new.

The Negros Museum in Bacolod City, a stately building that once housed the provincial government, narrates the island’s story, from its pre-colonial past to the boom and bust of the sugar industry. Its main draw at the time was “Tugyan sa Tawo,” a retrospective exhibition of Charlie Co, one of Negros’ most important contemporary artists. For four decades, Co has chronicled the island’s joys and anxieties through vibrant imagery, reminding visitors that Negros’ history is still unfolding, and art is one of its sharpest mirrors.

From there, we found our way to the Art District, a city block transformed into a buzzing hive of creativity. The Boho-chic neighborhood has street murals, indie galleries, pop-up shows, cafés, bar, and open spaces where we saw millennials and Gen Zs more focused on actual mingling than social media. At its core is the Orange Project, a collaborative space co-founded by Co and Victor Benjamin Lopue III. What began as a bright-orange-painted interior has blossomed into the epicenter of Bacolod’s contemporary art scene.

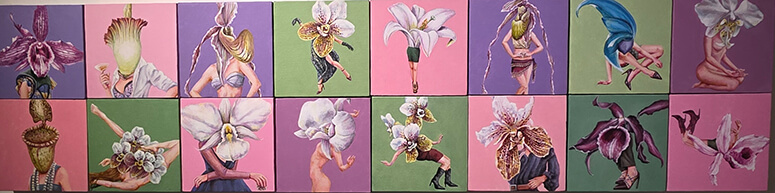

During our visit, two shows caught our attention. Erika Mayo’s “Kill Your Darlings,” curated by Maureen Austria, was an unflinching meditation on motherhood through the recurring motif of cows, complete with rituals, contradictions, quiet grief, and even an interactive room. Upstairs, “Flora Filipina” showcased works by the all-female collective Floral Artists Manila, each piece celebrating Philippine flora while doubling as a call to protect the country’s endangered ecosystems.

Standing amid these exhibits, it was impossible not to marvel at how Bacolod embraces both heritage and innovation, how a city rooted in sugar and tradition has also become fertile ground for new voices and visions.

In the end, that’s Bacolod’s magic: a city that honors its past without being trapped by it, and one that embraces the new without discarding its soul.