Ceviche and the vibrant flavors of Peruvian cuisine

Peru has over 3,000 varieties of corn, declared chef Carlo Huerta proudly, during a recent cooking demonstration at the Albertus Magnus Building in UST. The corn in Peru is amazing, he added. The kernels of the variety called cancha can grow as big as one inch and they’re sometimes dried and toasted before being used in recipes.

Huerta’s cooking demonstration was part of the celebration of the 50 years of diplomatic relations between Peru and the Philippines. A collaboration between UST, the Embassy of Peru in Thailand, and the Consulate General of Peru in Manila, the master class aimed to highlight the rich heritage and cultural significance of ceviche in Peruvian cuisine.

“We believe this event will be a memorable opportunity to explore the culinary traditions of Peru and strengthen ties between the two countries,” said Nadine Escaño, honorary consulate general of Peru in Manila.

They couldn’t have chosen a better dish to showcase the vibrant flavors of Peruvian cuisine. In fact, ceviche has been recognized by UNESCO as an “Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.” Unique in its preparation, ceviche consists of fish and various kinds of seafood marinated in an acidity and seasoned with herbs and spices. The acidity could come from vinegar or citrus fruits such as lemons, oranges and limes. Other South American countries (and the Philippines) have their own versions of ceviche but in Peru, it has a special significance. It’s considered Peru’s flagship dish.

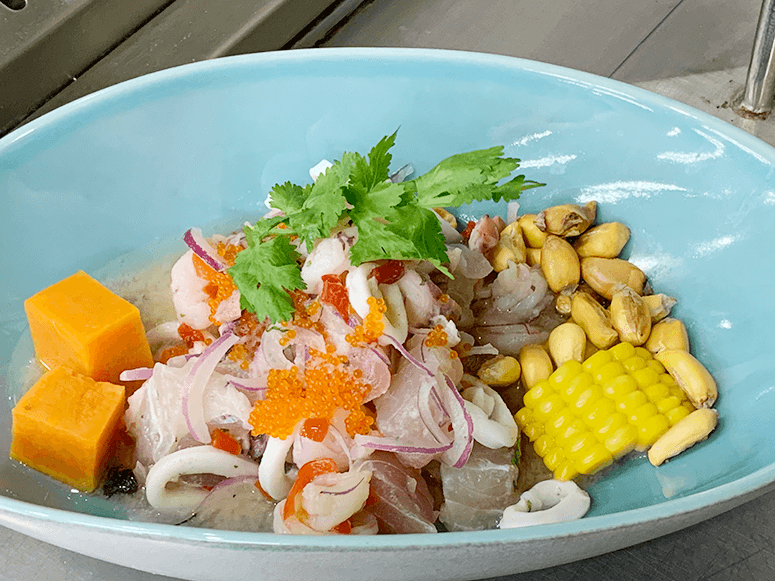

While seafood is the primary ingredient in ceviche, various touches make the Peruvian ceviche unique. There is, for example, the aforementioned cancha. Harvested during the months of March and April, the cancha is a variety of corn roasted or deep fried, and often served beside ceviche to add crunch to the dish. Peruvians also sometimes serve their ceviche with a side of sweet potatoes. The sweetness balances the spiciness of the seafood.

For the master class, Huerta demonstrated how to make mixed seafood ceviche. He first poached calamari and prawn tails in hot water, then placed them in a mixing bowl together with the grouper that had been cubed into 1 ½ cm x 1 ½ cm. Then he seasoned the mixture with sea salt, Hondashi rocoto juice, garlic and ceviche base (made with celery, white onion and limo, a chili milder than siling labuyo). A final touch of fish fumet, lime juice and coriander leaves and the ceviche was ready. He then arranged it in a bowl and drizzled all over the seafood the dressing called leche de tigre or tiger’s milk because of its punch. Garnished with tobiko and cilantro leaves, it was served with a side of sweet potatoes.

To the delight of the class, Huerta encouraged everyone to have a taste of the ceviche he had prepared. The tuna and the seafood tasted everything it promised to be: tart, spicy, and fresh, whispering of the sea and of the myriad influences that compose its creation. The cancha was crunchy and smoky, reminiscent of our own Ilocano chichacorn.

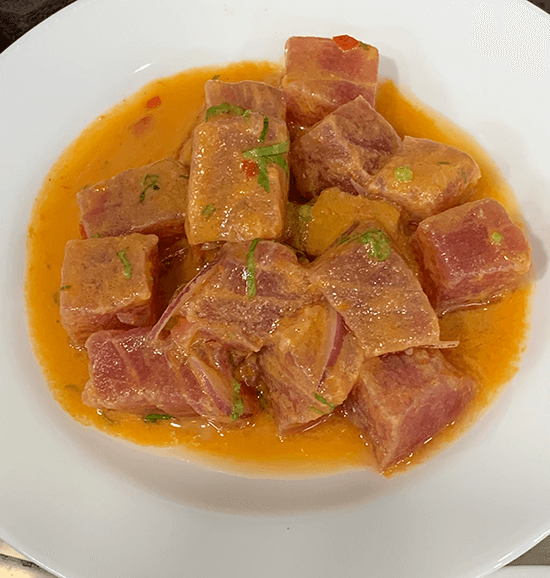

Huerta advises choosing only the freshest seafood, preferably the catch of the day, to make ceviche. As a chef, he also makes sure to use only sustainable seafood. For the cooking demonstration, he used tuna that had been caught in the seas of General Santos City in Mindanao, which he says is sustainable and safe.

“Knowing how to make ceviche opened doors for me,” Huerta says. He started his first restaurant overseas in Ecuador with ceviche as the main attraction. Today, as executive sous chef at Shangri-La at the Fort, he serves not just ceviche in Samba, the hotel’s Peruvian restaurant, but also other specialties such as lomo saltado (similar to the Filipino bistek Tagalog), pastel del choclo (Peruvian corn pie with beef tenderloin and quail egg), parihuela (Peruvian bouillabaisse) and pulpo al olivo (octopus carpaccio). But for Huerta, ceviche is still the star. In Samba’s menu there are 10 kinds of ceviche.