I got vaccinated abroad as a tourist. When can Filipinos have their turn?

I am a 21-year-old Filipino student spending my second semester abroad to live with my parents. Less than a month since I arrived here, I already got inoculated with my first dose of the COVID-19 vaccine.

It was undeniably exhilarating at first, but the excitement didn’t last long. There was a lingering feeling of guilt knowing that a Filipino like me has received the vaccine this early.

Back at home, we have a long way to go before we can even imagine living in a post-pandemic world.

With the anxieties brought by the global pandemic, my Overseas Filipino Worker parents decided that I should take advantage of the remote learning set-up and spend the semester with them. It has been almost two years since we’ve last seen each other. It was out of sheer privilege that I could travel.

The whole spectacle of the Philippines’ vaccine procurement has kept the public on the edge of their seats after the government promised the first batch of vaccines would arrive in February. Since the pandemic began, the president has maintained that the vaccine is the end-all solution—even boldly forecasted that it would arrive by December 2020.

However, the first hurdle in the country’s planned mass vaccination program came years before the pandemic struck the country — vaccine hesitancy, which isn’t even that surprising.

The hesitation of a very antagonized public stems from the gross mishandling of the Dengvaxia controversy, which lowered confidence in vaccine effectiveness.

On top of the vaccine hesitancy, the government had the audacity to illegally vaccinate members of the military and the Presidential Security Group before the Food and Drug Authority approved the use of the first vaccines in the country. While other countries started their mass vaccination programs as early as December 2020, we watched on the sidelines as we dealt with the late and questionable vaccine procurement, rising number of cases and emerging COVID-19 variants.

One year after the Luzon lockdown, while most countries are rolling out or, at the very least, developing their vaccines, we have resorted back to curfews, checkpoints and liquor bans. The health secretary? He’s still going around cities for optics with his meter stick and free face shield giveaways.

This scenario is far from what’s happening in the Middle Eastern country where I am currently staying. I grew up in its capital city and to go back at a time like this feels surreal.

The G20 country overwhelmingly exceeded my expectations in terms of containing the spread of the virus. Everyone seems to be integrated into the “new normal” with their economy gradually opening up.

Upon arrival, I was asked to download a contact tracing app, which can also be used to request for gathering permits, free swab test appointments and health assistance. The same app is presented whenever I enter establishments. I disclosed my health status— whether I just arrived from abroad, have been exposed to a COVID positive person, or have been immunized by a COVID-19 vaccine. We’re only required to wear face masks, not face shields.

In the Philippines, on the other hand, authorities merely ask you to fill up a contact tracing form in every establishment you enter. I have filled out countless of these forms, but no one has contacted me to advise any exposure from the virus. Moreover, we still have no free mass testing and we’re the only country that requires the use of face shields in public spaces.

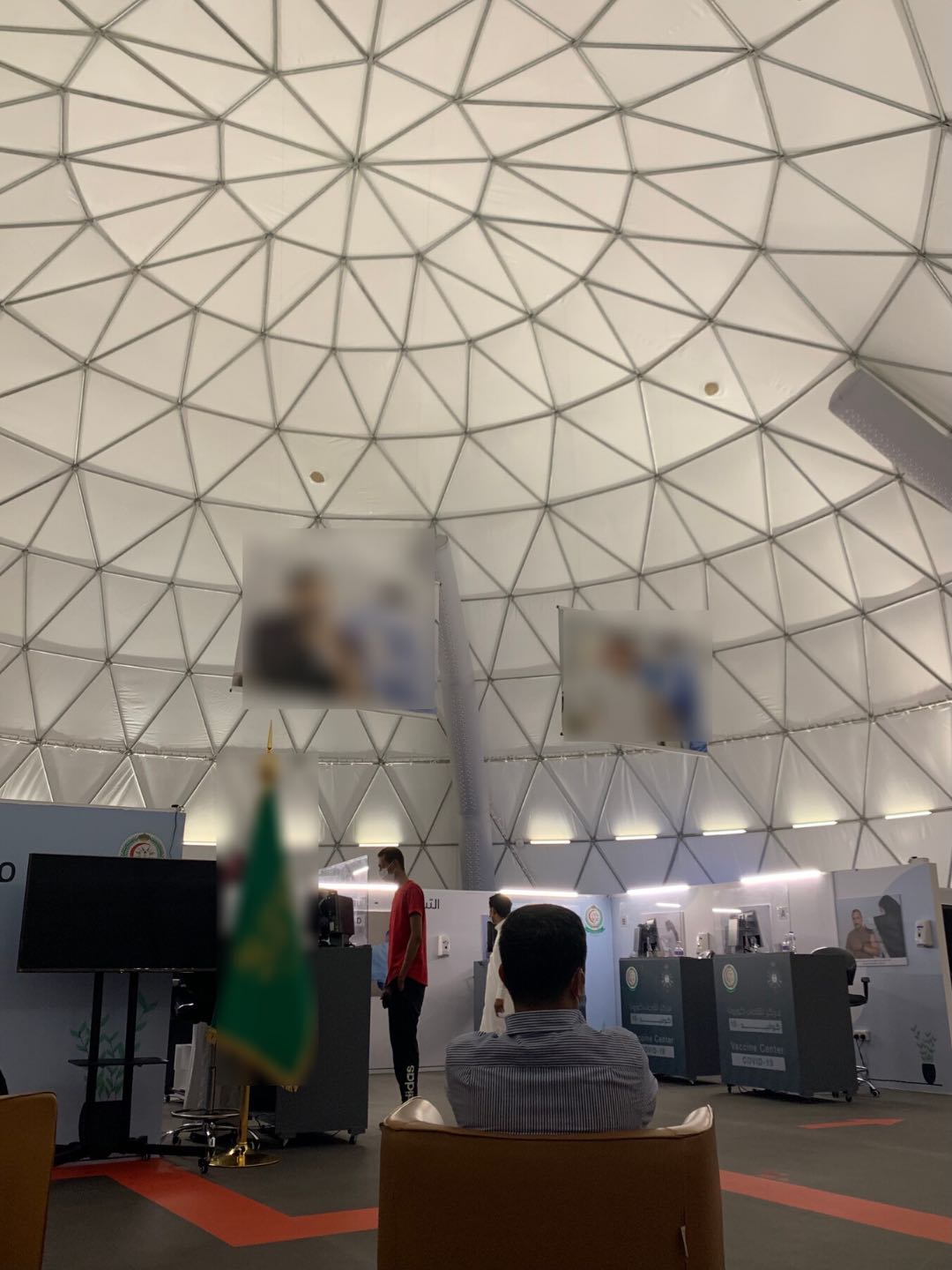

It was never my parents’ plan to have me inoculated with the COVID-19 vaccine because they didn’t think it would be possible since I was only a tourist. But three weeks after my arrival, I got injected with the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine for free when I lined up for it in a vaccination center.

I only felt the minimal side effects 12 hours after the injection. I experienced pain on the injection site, heaviness in the injected arm and slight chills.

Despite my fear of injections, I couldn’t contain my excitement. The idea couldn’t sink in—that after a year of the pandemic ravaging the whole world, I finally received a dose of what could signal the end of this global health crisis.

It is worth noting that even though I am merely a tourist here, I was given a chance by the foreign government to be vaccinated with their resources. It is truly mind-boggling how something so impossible in the Philippines is just the bare minimum in other countries.

Yet there is something unsettling about getting vaccinated this early while millions of Filipinos have yet to see a concrete vaccination plan. Thousands of Filipino healthcare workers — who are once again stationed in COVID-19 wards reaching full capacity — have not even been inoculated with their first dose yet.

As of March 24, this Middle Eastern country has vaccinated more than 3.6 million people. This is equal to vaccinating almost one-fourth of Metro Manila.

They have opened vaccination centers across major cities, universities and soon in community pharmacies that will be available to the public for free.

Meanwhile, the Philippines, which has used donations to vaccinate over 508,000 people as of March 24, has yet to receive vaccines that were supposedly purchased using the $14.29-billion loans from multiple financial institutions. Some mayors even jumped the priority line and got themselves inoculated with the limited vaccine supply, which we haven’t even administered to all the healthcare workers yet.

The government’s late procurement is startling to see, considering that the country’s curve was never really flattened.

I stand here vaccinated — thousands of kilometers away from my fellow countrymen — but in solidarity with them, especially the healthcare workers, in holding the government accountable for their criminal negligence during this crisis. We deserve better than government officials getting away with violating health protocols, VIP testing and vaccinations, cracking down on dissenters and progressives and trillions of international loans that are nowhere to be found. All while millions go hungry and unemployed.

We can no longer stand idly by as this corrupt and criminally inept government continues with its militaristic pandemic response at the expense of public health.

As the country now sees its highest surge of cases since the pandemic, it seems like we’re worse off than when this all started a year ago. Yet, Malacañang is even bold enough to claim that its pandemic response is “excellent” compared to other countries.

It is a wonder where they get the confidence to gaslight people on national television, when we have yet to see a free mass testing initiative, a unified contact tracing system and a mass vaccination program. Filipinos have been asking to prioritize public health since day one, but it seems the government is hell-bent on keeping the country in the chaos we’re in.

One thing’s for sure—the country’s pandemic response isn’t “excellent,” but a shameful failure. We have continuously fallen behind since the beginning because of the blatant incompetence of those in power. The question now is, until when can we let them fail us?

This article first appeared in Tinig ng Plaridel, the official student publication of the UP College of Mass Communication.