Money, fame, fraud, and the business of influencing

A special report on influencers, algorithm manipulation, click farms, and how marketing and advertising companies are defrauded.

Instagram exploded into the social media landscape a decade ago and it became a game changer. Before Instagram, there were blogs, entries of which were filled not just with photos but with stories of what happened to the authors during the day/ week.

Instagram is the abbreviated form of the blog—a quick upload of a photo with a caption, and it was one “update.”

It overtook blogs in popularity because its user interface was simple and required minimum effort. So easy that even people who don’t have a love affair with writing can enjoy using the photo- sharing platform—“Look, Ma, an emoji is considered a caption!”

Coupled with better mobile technology with cameras that produce stellar-quality photos and third party photo-editing apps, Instagram has become the photo- sharing, social networking app of choice by over one billion people as of last count by Statista.

Users spend an average of 53 minutes on it daily, with 63% aged 18 to 34, half of whom are female.

Companies, brands, and PR agencies saw the huge marketing potential of this app because of that growing population, and Instagram influencer marketing was born.

It did not take too long for companies to allocate a chunk of their marketing budget to these rising Instagram stars in the hopes they could increase brand awareness and promote products or services.

And because Instagram influencer marketing was still without precedent with no real way of measuring effectivity (unlike with blogs where click-throughs and impressions can be tracked), companies were in unchartered territory.

Tapinfluence, a social media marketing company, and Altimeter conducted a study on the state of influencer marketing by interviewing influencers, and the report found that over 69% admitted that their motivation to become an influencer was to earn money.

Earning easy money by posting photos, compared to the traditional way of earning it, is a great motivator indeed. Once an Instagrammer amasses a large number of followers (think tens of thousands and above), the money he/she can potentially receive as payment to promote services or products becomes “decent.”

Working the system

Since advertisers and brands still base their rates on follower count rather than on authentic engagement and sales conversion (which is frankly difficult to prove), this encourages ethically-challenged people to take shortcuts to increase follower count, finding questionable means to manipulate the Instagram algorithm and “work” the system.

According to Chavie Lieber of Business of Fashion, “influencer fraud—whether it’s buying followers or hiring ‘click farms’ to like or comment on posts, (would have cost) advertisers $1.3 billion (in 2019).”

In the Philippines alone, a sizable number of consumer-oriented companies have taken to contracting Instagrammers by paying them P30,000 per post or more.

A report released by Hype Auditor states that over 61.89% of Instagram influencers with over one million followers in 2018 ‘have the highest rate of inauthentic comments.’

Sadly, most of these companies including well- known retail giants and beauty brands were, in more ways than one, victimized by influencer fraud especially during the earlier days before analytics companies made Instagrammer data available.

Even more disturbing is the fact that a handful of these influencers’ dishonest schemes have managed to slip past Instagram, earning them that “verified” blue check beside their names.

Some of these verified Instagrammers even have ties to traditional media and belong to prominent families in society. Surprised? I was, too, but the analytics reports of companies like Social Blade and Hype Auditor don’t lie.

Coupled with a poll that I conducted last year, over 4,000 Philippine-based Instagram respondents have virtually pointed their fingers at those same “suspects” who were artificially inflating their numbers.

If anything, the reports have only revealed the true nature of these “influencers”— that they were willing to put their own integrity on the line by being dishonest about the authenticity of their follower count, all for popularity and with the highly probable end goal of securing a big piece of the companies’ influencer marketing budgets.

Influencer fraud, padding numbers

So how do these ethically challenged Instagrammers manipulate their follower count and game the system?

1. Buying followers and likes: This has become one of the quickest (though now easily detectable) ways to gain a huge follower count.

Many of these new followers are empty shell accounts with zero to fewer than five posts. These follower accounts were created by third-party companies (also known as click farms) with the sole purpose of following their customers, and one look at these accounts will already show you that they don’t belong to “real” people.

The same Business of Fashion article mentioned that Instagrammers can pay as low as $16 for 1,000 followers.

Click farms offer followers and likes for low prices, using internet bots or software applications that perform semi-automated or automated tasks (follow and like). Upon payment, the Instagrammer will immediately get a trickle of new followers.

In 2014, Instagram clamped down on this practice by eliminating fake accounts which resulted in between 20 and 70% drop in follower count among influencers.

Instagram still purges fake accounts, but the click farm industry continues to grow, a clear sign that this practice is still strongly adopted today.

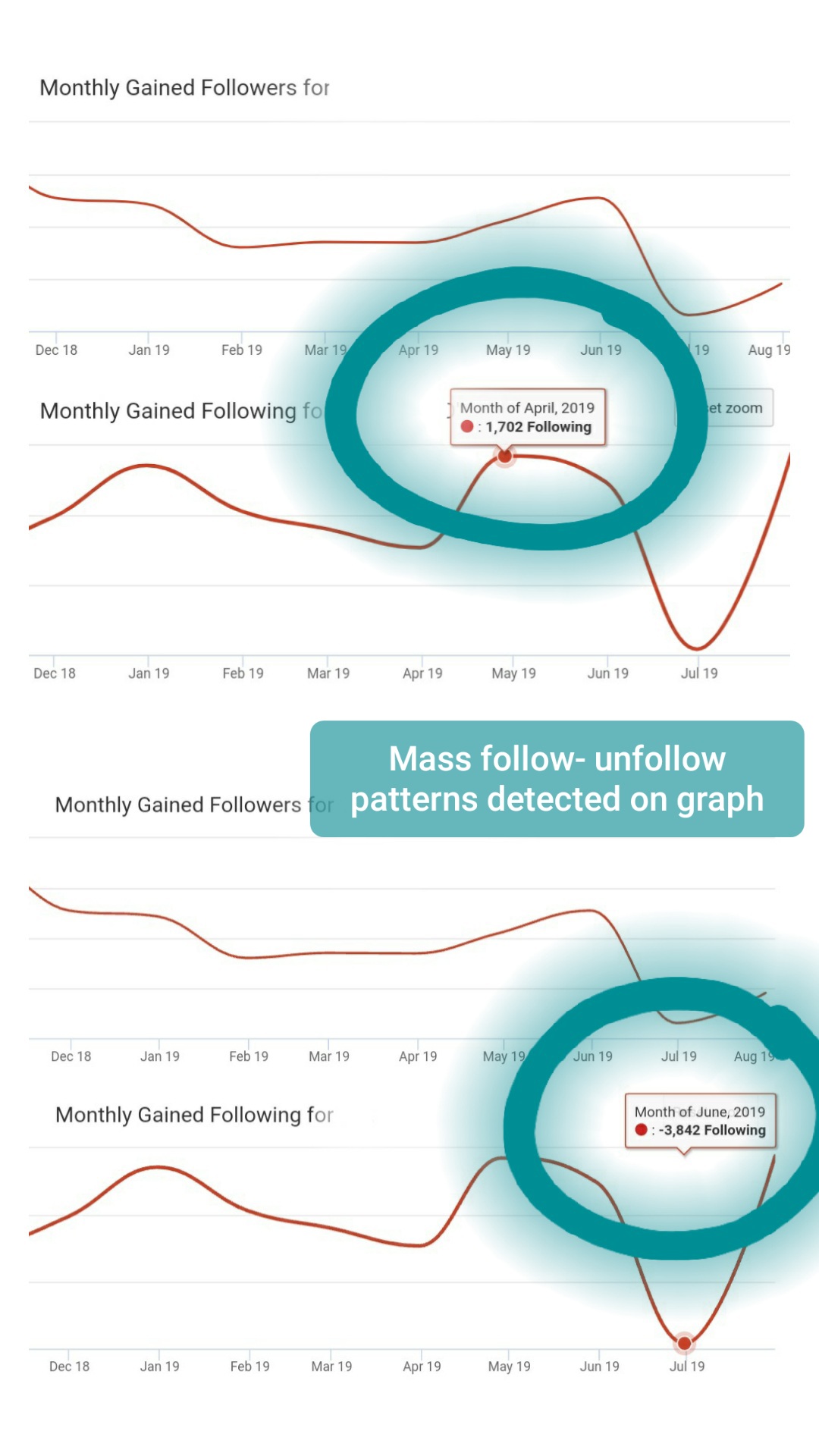

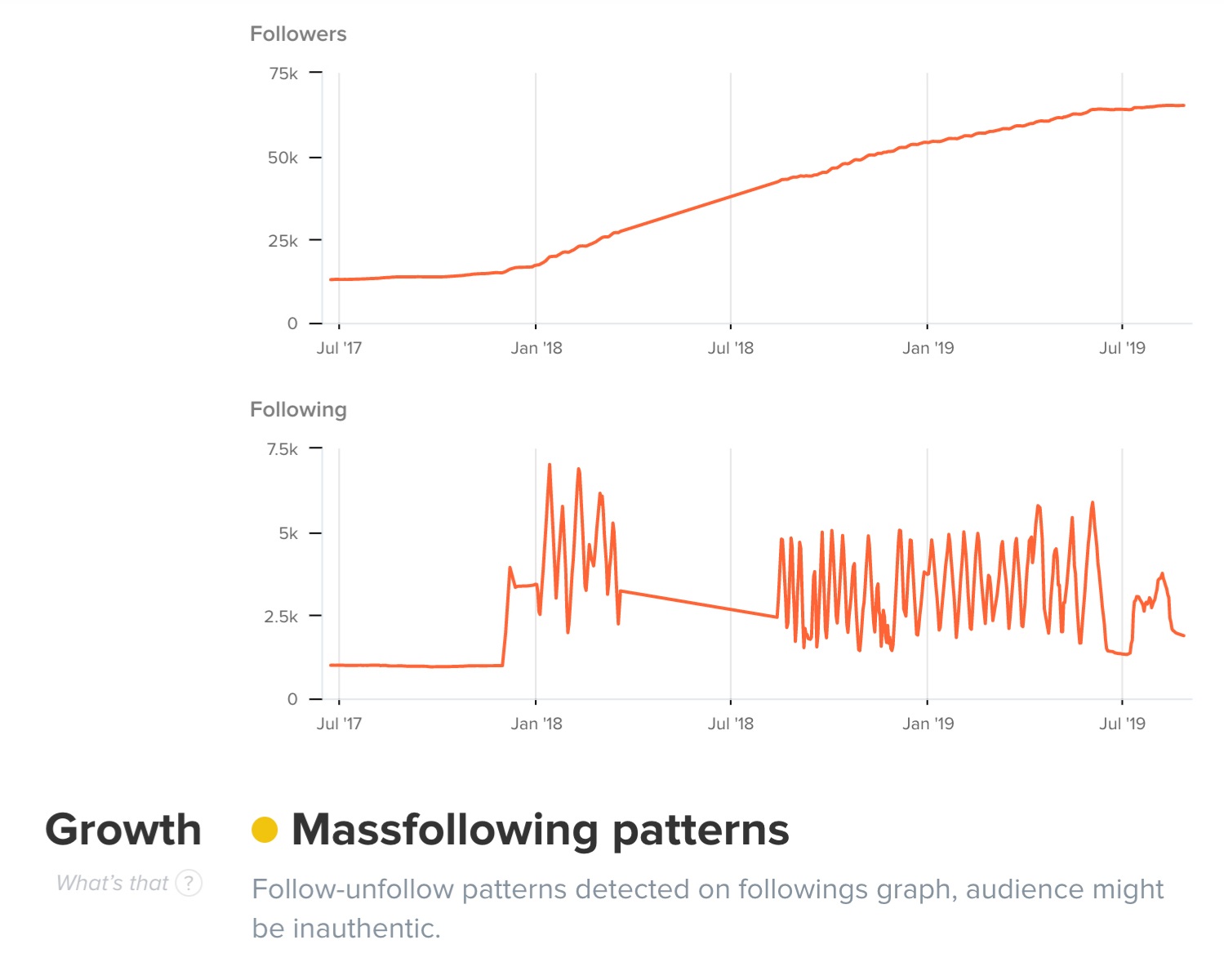

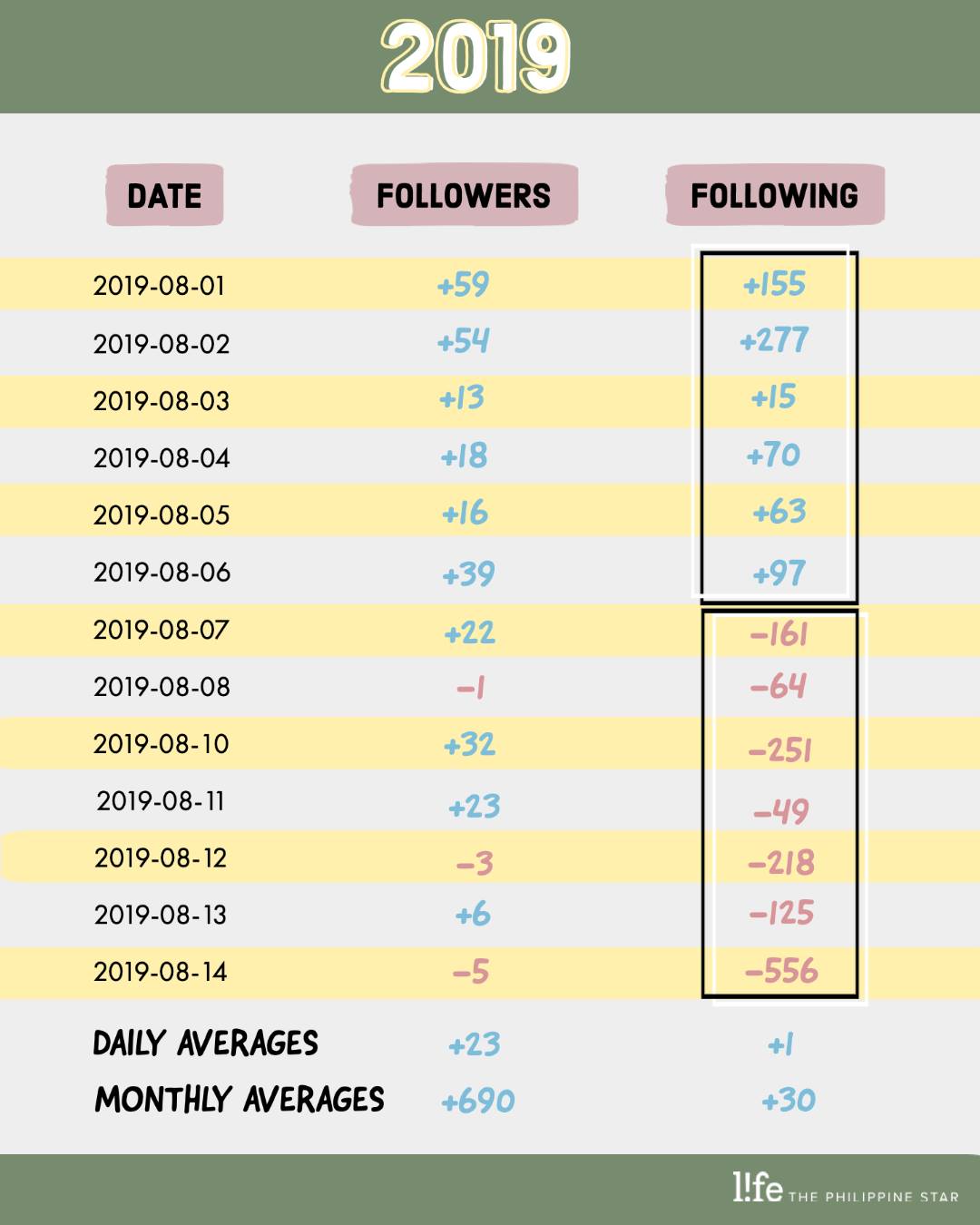

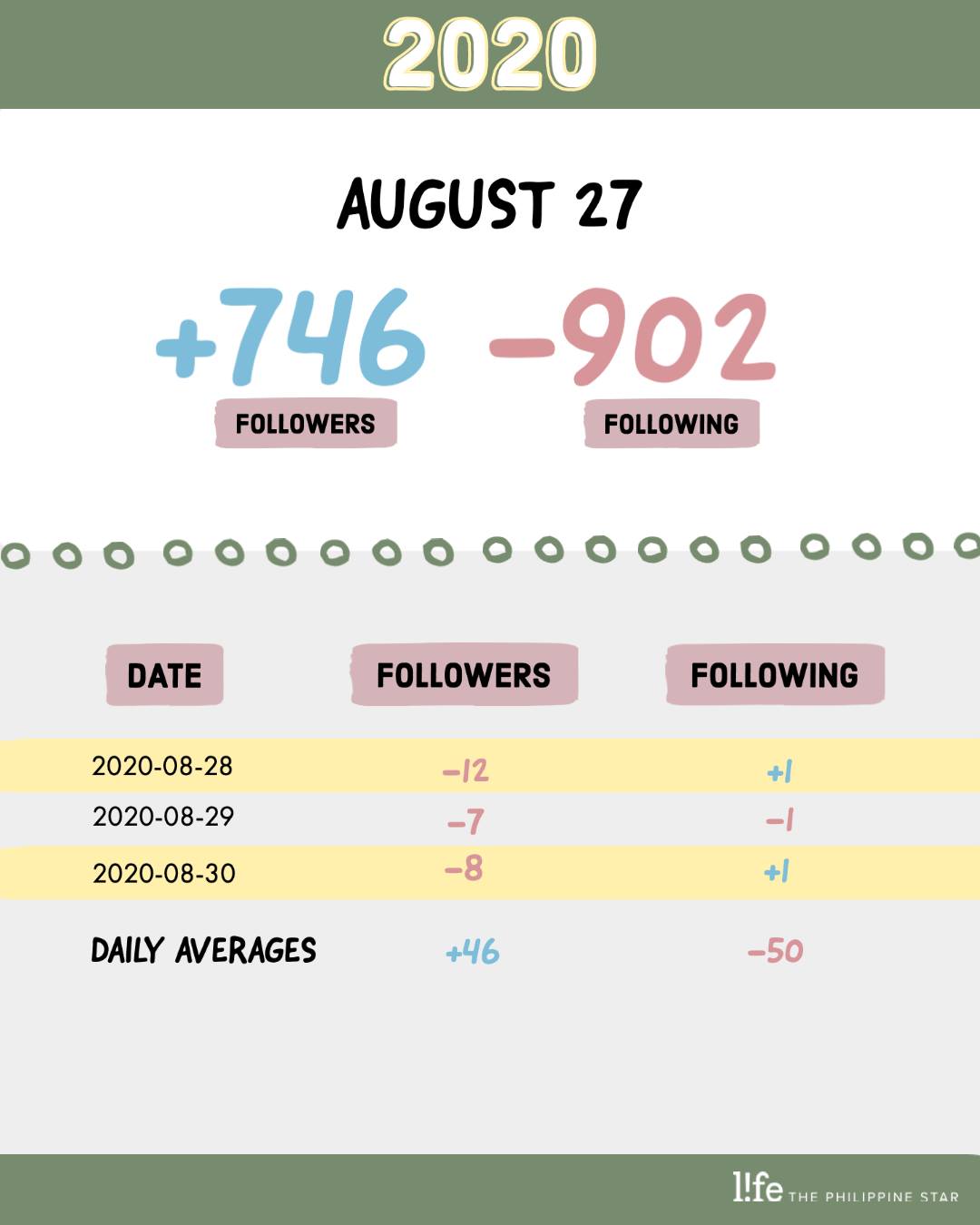

2. Follow for follow, like for like: Some Instagrammers have also inflated follower count by regularly mass-following hundreds of other Instagrammers through certain tools and apps based on a demographic filter criteria.

This is done with the assumption that those who get followed will reciprocate by following back. Days later, the same influencer unfollows those people.

Many have been fooled by this, following back an influencer, only to find out they’ve already been unfollowed. “Likes for likes” works in a similar way.

Earning easy money by posting photos on Instagram is a great motivator indeed. Two studies found that over 69% admitted their motivation to become influencers was to earn money.

Influencers follow hashtags, do “spam likes” and leave one word comments or single emojis on every photo under those hashtags, with the expectation that the other Instagrammers whose photos got liked, will return the engagement.

This is very deceptive, as the “vanity metric” of likes or follows procured through these methods do not allow for content to be properly viewed or be directed at the intended audience.

According to University of Baltimore professor Roberto Cavazos, who was interviewed for the Business of Fashion story, these “transactions are clearly not what brands have in mind when creating and paying for campaigns.” And if brands don’t regularly monitor the influencer’s Instagram analytics, they can be easily deceived.

3. Instagram pods: Instagram pods consist of people within their circle. Each pod member comments on and likes fellow members’ posts to boost engagement rate and manipulate Instagram’s algorithm, making those posts or profiles more visible to potential followers.

If you dissect the Instagram posts of these influencers, you will notice the same group of people commenting. In some amusing cases, their comments are not even be related to the influencer’s photo caption simply because they did not bother to read them.

A report released by Hype Auditor states that over 61.89% of Instagram influencers with over one million followers in 2018 “have the highest rate of inauthentic comments” and it is not just largely because of their own actions, but also because of the “spam methods that use other influencers and Instagram users to grow their accounts.”

Engagement inauthenticity has become inexorably linked to Instagrammers with bigger following. Many leave “shoutout” request comments (unrelated to the photo post) in the hopes of getting noticed by the influencer and his/ her other followers—it’s almost like these Instagrammers use others’ posts as free advertising space to promote themselves.

4. Promos/ giveaways: Who doesn’t want a chance to win something? Another easy way to gain followers instantly without having to pay for them is by conducting contests and promotions with the promise of attractive prizes.

Some of the “big draw” prizes include new mobile phones and coveted designer bags. The mechanics are simple—the account requires you to follow them, like their posts, and then tag other friends in the comments section.

The growth of follower count can be organic, swift, and exponential, but the followers are not authentic—they followed only for a chance to win something. These followers will also be quick to unfollow the account once the contests end.

It is interesting to note that many of these followers are also newly created accounts with almost no content in them, as they were set up solely to join contests like these.

Privileges that come with influence

With a strong follower count, many are quick to take advantage of the privileges accorded to them because of their power to influence.

Influencer fraud and bad behavior have become recurring subjects over dinner conversations among marketers and industry people in the last few years, up until recently.

Lesley Tan, a former hotelier and PR executive, detailed that “during my time working for an international hotel in Singapore, I received around a dozen requests from influencers a day, so about 360 requests a month.

In the Philippines alone, a sizable number of consumer-oriented companies have taken to contracting Instagrammers by paying them P30,000 per post or more.

“I have received numerous brazen requests—a memorable one was a lifestyle influencer from the UK who was actually vetted by our Europe PR office, whom we did take on an all-expense paid trip via Singapore Airlines Premium Economy and a Premier Suite at the newly renovated hotel wing, in exchange for a blog writeup tagging the hotel and the airline, with at least five Instagram posts.

“While our company kept our end of the agreement, she just posted Instagram stories and ‘seen-zoned’ messages from our Europe PR office after her trip.” Said trip set the hotel group back by approximately $15,000 (P725,000).

It must be said, though, that becoming corrupted by this kind of “power” is nothing new. Even before social media, this same kind of corruption was already rife within traditional media, as stories of editors openly requesting for complimentary airline tickets (business class with seats up front preferred), five-star hotel stays, expensive beauty treatments, and dinner parties for 10 (sometimes more) with the (sometimes empty) promise writing about it have become commonplace, although only talked about among industry insiders and in hushed voices.

Covid and collabs

And then, Covid-19 happened. Suddenly, those fat collaboration payments and sponsorship deals have all but disappeared almost overnight.

Companies furloughed their employees and slashed their marketing budgets. While some of these influencers have other revenue streams (they have actual jobs and businesses outside of social media), others were left grappling with the grim reality a financially unstable future as a result.

A food influencer got into hot water after being accused of bad behavior on top of taking advantage of home kitchen-based small businesses by requesting for “collabs” at the height of the pandemic—free food in exchange for posts on Instagram.

Some took to other platforms like TikTok and YouTube to create more entertainment-centric content to stay relevant as well as to attract new followers and potential sponsors.

The crisis that crippled the world has also been a lesson in pivoting and adapting, so it was interesting to see the more entrepreneurial influencers finding ways to monetize their numbers by creating small businesses (food, mostly) that allowed them to convert their followers into paying customers.

Speaking engagements on webinars have also become a source of income for some, while others took to creating content for other companies on the side—as large-scale ad productions had to be halted—to make extra money.

Performance and sales-based collaborations between influencers and brands (rather than brands just paying influencers upfront marketing fees) are likewise on the rise and are more mutually beneficial.

And on an encouraging and positive note, a number of influencers also used their influence for the greater good by setting up fundraising events and drives to help provide protective gear and essentials for front liners and for the less-fortunate living in dense communities.

Not surprisingly, social media use has increased since the pandemic began even though ad spending has decreased. And while influencer marketing was halted at the pandemic’s onset, marketers are also slowly realizing that now is a good time to initiate work with them again, especially since more people are spending money online than off (physical retail).

The crisis that crippled the world has also been a lesson in pivoting and adapting, so it was interesting to see the more entrepreneurial influencers finding ways to monetize their numbers by creating small businesses.

Marketers and brands have also become more discerning about which influencers to tap, making sure their marketing money goes to the right people for the job.

Realistically, there will always be those influencers with questionably acquired followers who still get projects. Unfortunately, this society also still places gravitas on “who you know, who you’re married to, or who your family is,” so unscrupulous influencers with this extra “edge” will milk it to their advantage.

Meanwhile, the rest of the influencer population have to work doubly hard during this crisis to produce content that would make them attractive to advertisers.

According to a Global Web Index report generated last July, “how- to” tutorials, funny content/ memes, short- form videos between 15 and 60 seconds long were what respondents were interested in seeing, as they’re in search of what would ease their lives during the pandemic.

Influencer marketing is here to stay

While it’s true that marketing budgets have shrunk, influencer marketing projects won’t be drying out completely anytime soon.

If anything, influencer marketing has become more important now more than ever. Paid campaigns may have gone on hibernation for the time being, but brands and marketers have their eyes peeled and are constantly looking for potential influencers to tap for future projects.

Marketers now have—at their fingertips—analytics and metrics tools to help them identify authentic influencers and weed out the deceptive ones.

Free third- party services like Social Blade can already reveal basic information about an influencer’s follower following growth pattern and engagement rate.

Paid-service analytics companies like Hype Auditor produce more comprehensive reports and can dissect influencers’ follower demographics, audience quality score, and authenticity.

An extensive research on the personalities of the influencers is of paramount importance. Brands need to identify key priorities when allocating influencer marketing funds: are they contracting influencers to increase exposure or are they banking on these influencers to affect sales?

There are a lot of credible and legitimate influencers who produce top quality content, consistently engage with their followers, and care enough the product they’re promoting. To make influencer marketing strategies effective, brands and influencers need to work closely together to identify these goals.

This will ensure both parties have an equitable and symbiotic relationship. Influencer marketing via Instagram is here to stay. Companies need to understand that they should be contracting influencers whose personal values align with their brand values.

After all, they are still spending their money on them, albeit much less, and will continue to do so even with the current crisis.

Until another platform comes along.