‘You cannot rest your eyes’: Jigger Cruz has a mid-career retrospective

First came the exorcist of oil.

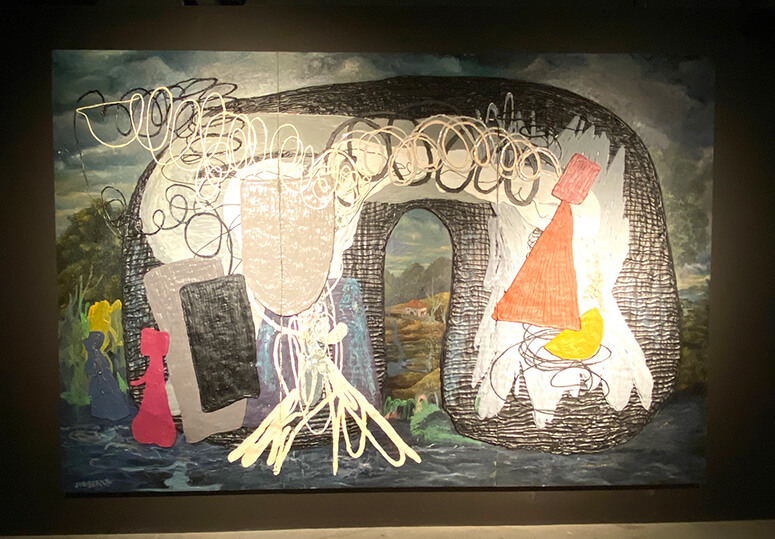

As Jigger Cruz walks us through “Hail Holy Eyes,” his mid-career show at the Metropolitan Museum of Manila, we are reminded of this early desire to purge. To clear the air of imagined or real demons. To excise and defile, even. Figurative works peek out from the corners beneath thick slabs of oil paint overlaying canvases like entrails speaking in tongues. The “old school” beneath is there to remind us of what needs to be overturned, cast out, replaced or reimagined. The colonial cloak of the West.

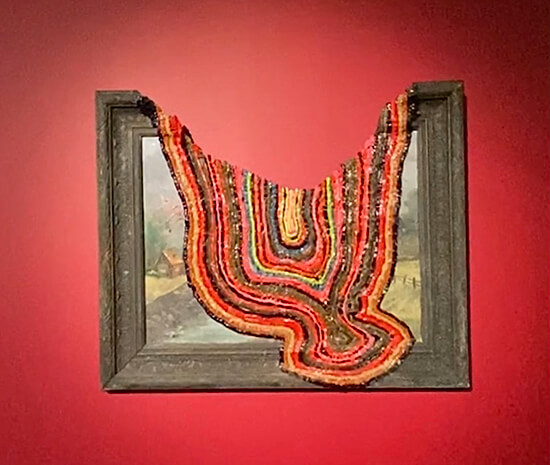

The simple act of “defiance and defacement” was necessary for Cruz, born 1984 in Malabon City, Manila. Even the frames, he points out, are an anachronism he’s consciously rejected.

Yes, as in an early work titled “Broken Sunday,” where a melting rainbow dissolves the upper frame, flowing and consuming the work beneath. “I remember that painting, when I was doing that was a time when, walang gawan paint, if you put a frame, it’s already old school, it’s not contemporary,” he recalls. “So I destroyed it. I wanted to make an annoying painting.”

Provocation can get you noticed, but it won’t take you that far on its own. Cruz developed a unique relationship with paint, particularly his beloved oils. Being colorblind, unable to distinguish purple and green tints, meant he evolved a more textural approach to the canvas, applying thick layers directly from tubes. Consuming the past. Worming and tunneling into the now.

His curator and friend, Norman Cristologo, accompanies our tour. In the earlier work, he notes, Jigger’s figurative layers reveal not a repurposed painting, but something he painted then “destroyed.” “The background is action, then I remove the layers,” says Cruz. “It makes the background a sort of abstraction.”

The visceral nature of the oil paint, scrubbing out something, evolves in later works into a raw materiality: the new construction is the point; no longer destruction.

As we walk through the Met, we’re surrounded by waves of sound alternating between soothing, enveloping, and churning cacophony. Cruz’s music, created on analog gear, with sound installations assisted by Erwin Romulo, is a complementary statement to the show, which spreads through six rooms and includes over 100 works—nearly all of them borrowed back from private collectors—that are maddeningly untitled, following no chronological order. “There’s just a little bit more religious imagery on one side of the exhibit,” allows Cristologo—referring to one room you enter through a metallic arch, as though inside a church, where the surrounding abstract canvases represent “the Stations of the Cross,” but in no particular order. “Actually, you see religious imagery in a lot of it. But there’s no theme; it’s a mixture of new works, old works, and sculptures. So each work, for me, directly relates to the one beside it, and the one next to it.”

Cruz is visibly pleased by the abstract soundscapes accompanying his own massive canvases. “I have a different experience each time I look at a painting,” he says. One recent, purely abstract mélange of swirling oils catches his eye: “I think it’s a sexy painting; you cannot rest your eyes.” Another features a black, asymmetric oval he calls a “portal” laid over what seems like an idyllic mix of seascape and forest in soft green tones, a faded background atop of which the portal beckons. This will evoke different emotions for Cruz whenever he looks at it. Perhaps he’s thinking about the process of painting that got him there. “I love being lost and staying lost in painting.”

The paint to him is “alive,” not just because the thick application takes years to dry, or tends to drip. It’s because the artist is still conversing with it. “Nothing is finished. The paint is unfinished. They’re all alive.”

It literally isn’t finished, says Crisologo, because it constantly bleeds and drips, changes, wrinkles and cracks over 20, 30 years. “If you’re a buyer or a collector, you should know that, and you should accept the fact that there’s going to be oil drips and stuff.”

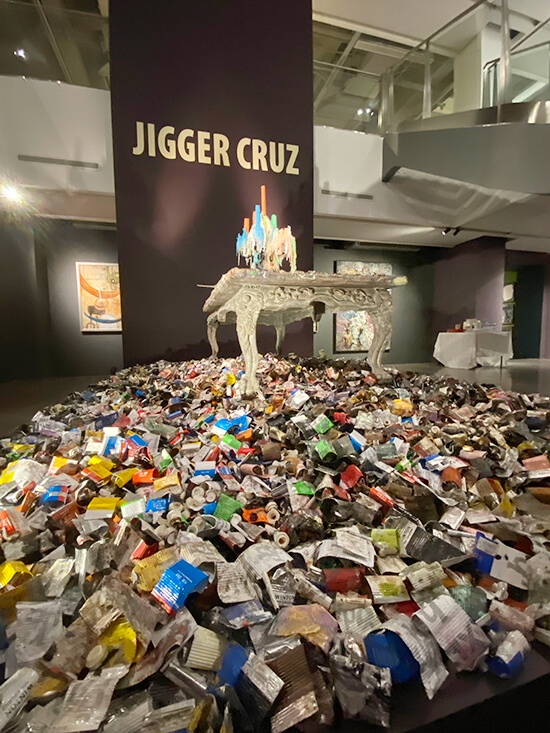

Several of his works pay tribute to his love of oils. At the show’s entrance, there’s a mountain of used-up tubes (Crisologo jokes “There’s been a lot of complaints from the other Filipino artists, because there’s no more stocks of oil paint”), atop of which sits an old wooden table coated in thick layers of dried paint, which he says is literally his “palette.” At the center of this table stands a melting psychedelic candelabra, straight from his studio. He says he included all this to make his friends who visit the show feel “at home.” Even his self-portraits are made up of spent tubes, rolled up and empty, and caps, and rubber gloves. Seeing the mountain of tubes is “orgasmic,” Cruz jokes.

To create this unique world we are surrounded by in the Met, Cruz had to move past punk aggro energy—rejecting the old—into a purer strain of iconoclasm that emerges in expressive gestures of chaos and texture. “Curiously, this lessens the cacophony, allowing us access to a far stranger universe,” Crisologo writes.

The output is impressive from this 41-year-old artist. I ask him if he ever gets stuck. “Yeah, I always feel that. But there’s always a way out.” He’ll shift to music, or ride his motorcycle, or spend time with his family. “I have a lot of outlets. Sometimes I stop painting. Sometimes I just don’t want to move.”

But while working on a piece, “There’s a momentum. Once I start a piece, I don’t want to stop. And it’s hard to get out. After that, I have to rest.”

Whatever enters his life passes through him into the work. “Some days I’m lazy, or stressed. Or I feel some other way. You can see each story in each layer of the process, in the painting.”

Downstairs, a final room of Jigger’s work is fronted by a large limestone sculpture he calls the exhibit’s “deity.” He repurposed it from two pieces of discarded material from a Cordilleras quarry, rendering it as a model with a 3D printer, then completing it large scale. His sculptures also pay passing tribute to older traditions, just before quietly demolishing them.

In parting with Jigger and Norman, I can only agree that this retrospective encompasses a complete world unto itself.

But it’s more than that. The work not only offers a world; it offers a world reborn, birthing itself anew.

* * *

“Hail Holy Eyes” by Jigger Cruz is now showing at Metropolitan Museum of Manila, MK Tan Centre, 30th Street, Taguig.