Art and the teaching moment

There’s a palpable boredom in the assembly room. An air of stagnation relieved only by a narrow window filtering in some sunlight. The floor, patterned with intricate shapes, seems to soak it all up. Facing each other across the hall, the meeting attendees are slumped over, slouching, some already napping. Anyone who’s ever sat through a meeting that’s gone on hours too long can identify with the unremarkable atmosphere of Francisco Goya’s 1815 painting, an oddly prophetic work that was meant to commemorate the 30th annual assembly of the Royal Company of the Philippines.

The meeting in question was called for as a discussion about the future of Spanish-Philippine relations. The Spanish empire had at this point reached a point of disintegration as a result of Spain’s military conflict against the French Empire in the Peninsular War. The costs—economic, military, human—were tremendous. Though “The Junta of the Philippines” was supposedly commissioned to memorialize the gathering of notable stakeholders, Goya cast a distrustful eye on his subjects: ruling monarch Ferdinand VII sits at the painting’s vanishing point, a pompous figure whose means of power are slowly diminishing, fading from his incompetent grasp.

1815_.jpg)

Goya lets us peek into that diminishment in real time. Beyond a saving glimpse of sunlight, there’s a tiredness in the room, a deathly pallor. These traits hint at Goya’s criticism of the Spanish monarchy as he sidesteps the typical contours of a commemorative portrait.

Garcellano’s version of Goya’s painting works as a good entry point to her artistic method. Less interested in breaking new ground, Garcellano prefers instead to put pressure on preexisting ideas, angle them in such a way that brings out a fresh insight.

A version of “The Junta of the Philippines” appears in visual artist, academic and writer Lyra Garcellano’s solo show at Finale Art File. Here, Goya’s virtuosic brushstrokes are replaced by Garcellano’s pencil-on-paper rendition: the shadows heightened, certain details blurred, the canvas miniaturized into a fragile sheet. Where does this transposition get us?

The exhibition’s title, “Land, Labor, Life: Tracing ‘Progress’ in Selected Notes,” essentially lays out all the artist’s cards on the table. By inquiring into the country’s colonial history of land and labor, Garcellano’s works—or “notes,” as she calls them—seek to intervene into our traditional notions of that word “progress.” She asks through these notes: On what—or whose—terms can progress be defined? And who reaps its benefits? In the case of her version of Goya’s painting, we are called to question: How do we understand this assembly—where men discuss trade deals and monopolies, circulation of goods and labor—from the point of view of the colony?

Garcellano’s rendition of the Goya painting works as a good entry point to her artistic method. Less interested in breaking new ground, Garcellano prefers instead to put pressure on preexisting ideas, angle them in such a way that brings out a fresh insight. It’s an approach that aims not so much to drill down on an idea’s essence or cohesive truth but to explore ways in which recontextualization can alert us to novel strategies of meaning-making.

Something, for instance, about the monochromatic reworking of Goya’s piece makes Garcellano’s version look like a photocopy, something that would circulate in textbooks around the country. Another pencil drawing, titled “Filipinos Labelled as Indios,” which features blurred-out faces dressed in Filipiniana and an eerily masked soldier looming over them, appears to hint at just that kind of posturing: When histories and identities are passed down, what narratives are lost? Which are foregrounded?

Garcellano displays a researcher’s mindset when approaching her art (her background as a researcher focuses on “the investigation of art ecosystems, as well as historical narratives that pertain to land, labor, identity, and migration,” reads one bio of her online). There is an impressive amount to learn from all this: from the LED envisioning of the Brandt line, a visual depiction of the divide between North and South economies, to various pencil drawings on paper that showcase the country’s colonial legacy of labor and women laborers. There is also, perhaps most interestingly, a composition of maps layered over with rocks that seem to denote the country’s ongoing territorial conflicts with China.

Taken altogether, in its showcase of intellect, Garcellano’s latest offering can be read as a visual essay, an archive of thoughts and examples constellating around an overarching argument. Of course, attendant to this method is the risk that, as insightful and thoughtful as the research and arguments are, the art itself cannot stand on its own, or is merely an appendage to the wealth of knowledge that it tries so desperately to embody. What are we to do with this knowledge?

Though the points the show raises—especially in its explorations of labor, geography, and colonialism—are urgent, a part of me questions: Why choose art to represent these issues in the first place? The format of the exhibition, right down to its title’s position paper-style formatting, raises an essayistic flag and underscores Garcellano’s background as an academic, as well as her commitment to produce art under the banner of that academic training.

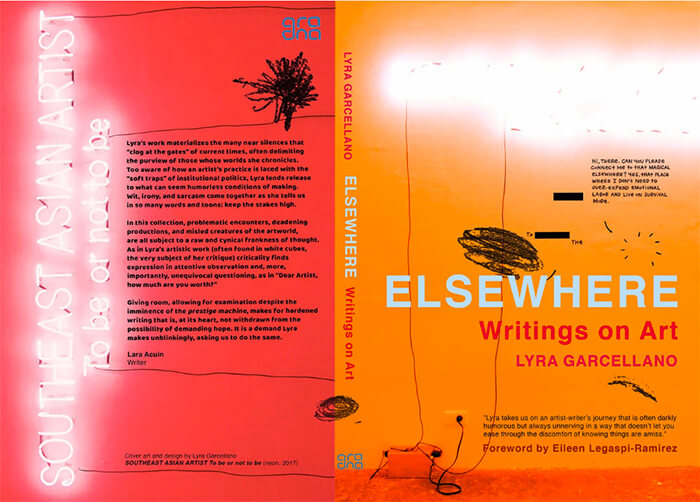

Earlier this year, Garcellano published a collection of writing, Elsewhere: Writings on Art, a selection of essays filled with fascinating and sharp insights on her journey navigating an art ecology driven by dehumanizing market forces and constraining structures of class, prestige, and profit. A part of me wonders whether this exhibition would have fit in better as a chapter in that book. Likewise, I can just as easily imagine the works in Garcellano’s show acting just as well as a set of figures accompanying a dissertation. In this sense, the show acts as an extension to Garcellano’s writing endeavors as she tries to locate within her art a teaching moment.

The exhibition notes, written by another academic, Carmita Eliza De Jesus Icasiano, furthers this case: The essay is filled with explications and explanations that rush to fill in the intellectual gaps one might encounter when experiencing the show. “The three drawings are rendered to provide insight on Philippine labor history dating back to our colonial past,” Icasiano writes. “The installation reflects on multilayered posturing of combined and competing forces over territory and land.” Here’s art as a game of interpretation, an elaboration of a thesis. But when the art becomes so tethered to these academic priorities, professionalized to the point of suffocation, what room is left for the audience to exercise their own agency in experiencing the show, to stumble upon their own revelations and surprises?

One especially cynical way to read these pieces is as solely inert objects waiting to be activated, to be assigned to students as an object of study for a term paper on postcolonialism. But the more I thought about this show, the more I grew suspicious of art’s capacity to stand in for research and scholarly practice. Garcellano’s dissertation art sits in between, undecided about the place it occupies between artifact and scholarly text. What happens when art is subsumed by the trailblazing research that preceded it? The unfortunate feeling is not quite dissimilar from the feeling of those assembly participants in Goya’s painting.