How Art Deco found its way into Filipino homes

The pathway that Art Deco took to conquer the world leads from Paris.

But in the Philippines, Art Deco came from America.

As the new exhibit “Art Deco: Modernity and Design in the Philippines, 1925 to 1950” makes clear, the Americans here in the 1930s brought their treasured Art Deco décor, furniture and knickknacks with them from New York, Chicago and elsewhere, and these items led Filipinos to try their own hand at the style.

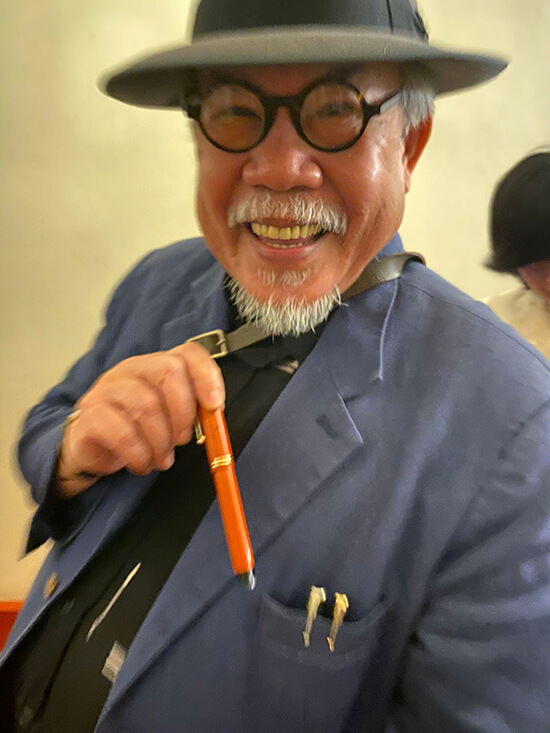

The just-opened exhibit at the National Museum of Fine Arts, unveiled in the “Spoliarium” Hall after opening remarks and a bit of period-era jazz from soprano Pauline Therese Arejola, covers two galleries and ranges from locally made furniture and dressers, ornate armoires and mirrors, to Flapper-style ternos, fountain pens (some supplied by “Penman” Butch Dalisay), busts and statues, and architectural models of key Art Deco-style buildings and structures in Manila, such as the Manila Metropolitan Theater, Rizal Memorial Coliseum, Misamis Oriental Capitol Building, the First United Building in Manila and the Quezon Memorial Shrine.

Paris showcased the Art Deco movement at the 1925 Exposition internationale des arts décoratifs et industriels modernes, and the world took notice. As the show’s title suggests, Art Deco brought a sense of exuberance and modernity to design—shown in movies like Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1927) and the lavish decor of the Roaring Twenties. That optimism was tempered by the Great Depression and WWII, but the spirit of Art Deco lived on. (You can even see it in the Oz design of the new Wicked sequel.)

National Museum of the Philippines director general Jeremy Barns sees Art Deco as “a guiding force towards national introspection,” shown in the response of local designers and craftsmen to the design movement from the 1930s onward. “By sparking conversations about the diversity of our expression, space and esthetics, we weave the threads of memory, identity and continuity that bring us to our future.”

For the show, guest curators Ivan Man Dy and Miguel Rosales scoured the homes and collections of the Philippines for items. One lender: Butch Dalisay, whose prized fountain pens share a case with fellow collector Augusto L. Toledo II’s vintage inkwells and bottles. They sit in a sleek, radio-inspired armoire of Narra supplied by Dy. “Joining this was a no-brainer for us,” says Dalisay, pulling out a 1928 Parker pen from his breast pocket. “Both in terms of aesthetic and mechanical design, the 1930s was really the top.”

Gallery VII focuses on “The Modern Lifestyle,” with a showcase of proudly Filipino carved furniture items (a set of Gonzalo Puyat & Sons chairs is a highlight), home displays of hairbrushes, vintage postcards, Cymbalist sculptures, and a Chabrol & Poirier porcelain European tea service supplied by Rosales.

Gallery X focuses on architecture and the design principles laid out in French exhibit catalogues like Meubles Nouveaux (New Furniture). But at home, it was a key piece of legislation—The Payne-Aldrich Act of 1909—that opened the door to American products freely entering the Philippines and allowed Art Deco to decorate those colonial homes. Soon, American popular culture—music, media, Hollywood movies—came to influence the aesthetic trends of Manileños.

But outside of Manila, it was the booming agricultural industries of the time—with huge profits generated by sugar exports in Iloilo and Negros Occidental, and cash crops such as rice and coconut in Bulacan, Pampanga, Laguna, Batangas and Quezon—that saw newly wealthy hacienda owners embracing the extravagant design and lifestyles of contemporary Art Deco.

Those homes became key sources for Rosales and Dy in staging “Modernity and Design in the Philippines.”

“We didn’t want to be focused on Manila,” says Rosales, adding the households of Negros Occidental were “a strong source” for donations for the show.

I asked Rosales how Filipino designers put their own spin on things. “You see it in the tropicalization of the décor style, the materials and motifs. Some wall reliefs with tamaraws, things like that.” Or the use of rattan, a local material, for seats, where the US would use stuffed cushions. In the ternos, Rosales says, “You can see the Deco patterns, but it’s still a very Filipino design.” “We didn’t have Flappers here, we were too conservative,” adds Dy. But the Art Deco influence is there even in the slimming terno, replacing the traje de mestiza by the 1930s.

Other Filipino imprints: “American Deco was very industrial, with chrome, metal,” notes Dy. “We didn’t see a lot of industrial designers here. Here, it was very organic. Mango, wood elements, rattan.” But still, the American influence came in through the pensionados—Filipinos sent to study in the US starting in 1903 who brought Western/US influences here.

Even with the Art Deco arches, stadiums, banks and theaters that came to characterize its public face, the goal for the show was to present the movement as it entered the day-to-day Filipino home. “I wanted to mix the everyday objects—to layer things and show how the movement permeated daily life—from the furniture you would have dinner on to the clothes you’d wear, to the jewelry and hairbrushes you’d use,” says Rosales.

This is a nostalgic look back at Filipino design that still resonates with notes of the future.

* * *

“Art Deco: Modernity and Design in the Philippines, 1925 to 1950” runs until May 31, 2026 at the National Museum of Fine Arts, Ermita, Manila.