Guillermo del Toro’s craft on display at MoMA

NEW YORK CITY—Easter was near. Spring was busting out all over. What a great time to visit the Guillermo Del Toro exhibit Crafting Pinocchio at New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA).

The Mexican director’s take on Carlo Collodi’s 1883 children’s novel weaves in many of his favorite themes: a child in an unnatural state, lots of macabre ambiance, and even some antiauthoritarian piss-taking (that Mussolini song). For the MoMA show, many of the main models and stages are recreated, bringing us into the creative process.

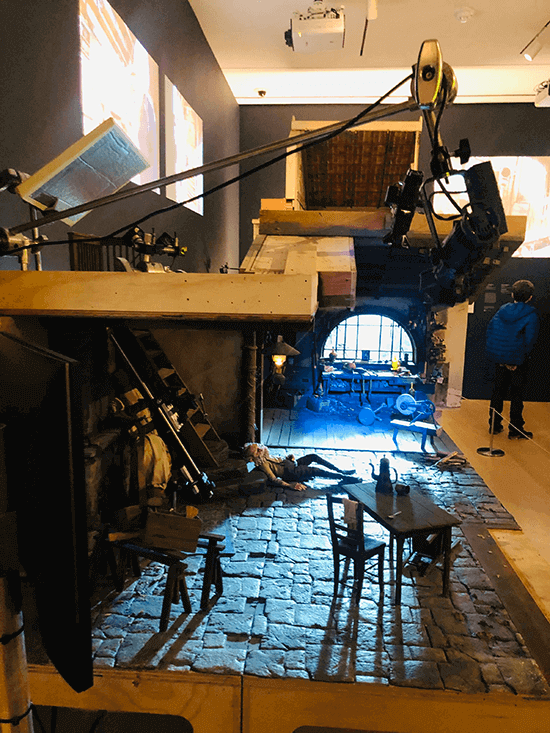

Devised to coincide with the release of the Netflix film last year, Crafting Pinocchio allows viewers to experience the movie set almost firsthand, showing an international collaboration between designers, craftspeople, and animation artists from Portland, Oregon, Guadalajara, Mexico, and England in bringing Del Toro’s vision to life. Stunning tableaus recreate the animation tables. Time-lapse videos show us each intricate move of the wooden maquette puppets as animators swoop around and adjust their limbs, frame by frame.

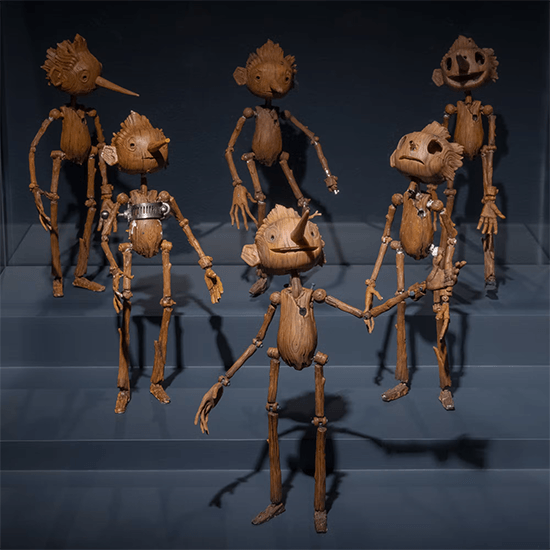

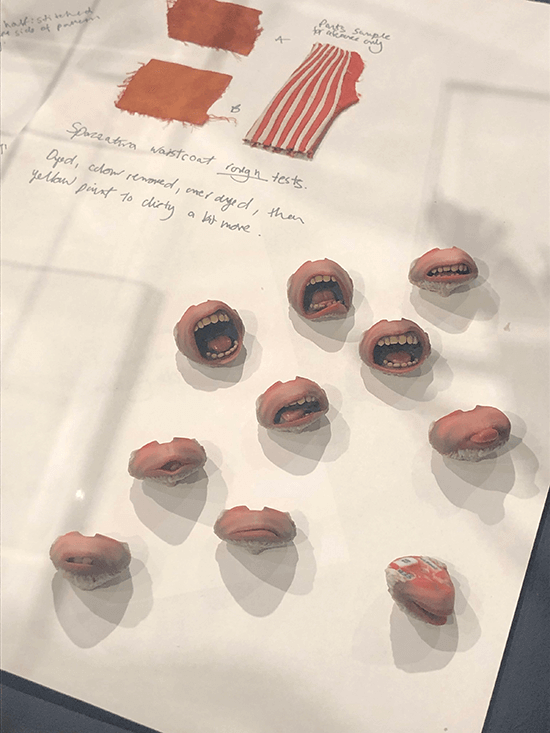

The upper level is dedicated to the animation work of ShadowMachine, the studio behind Robot Chicken and Bojack Horseman, which molded the physical models. It opens with a row of mounted pizza boxes, alluding to the process called “replacement animation." During production, over 870 3D-printed mouths were arrayed in open pizza boxes, allowing animators to more easily insert them one by one over the maquettes’ mouths during animation to convey realistic facial variations.

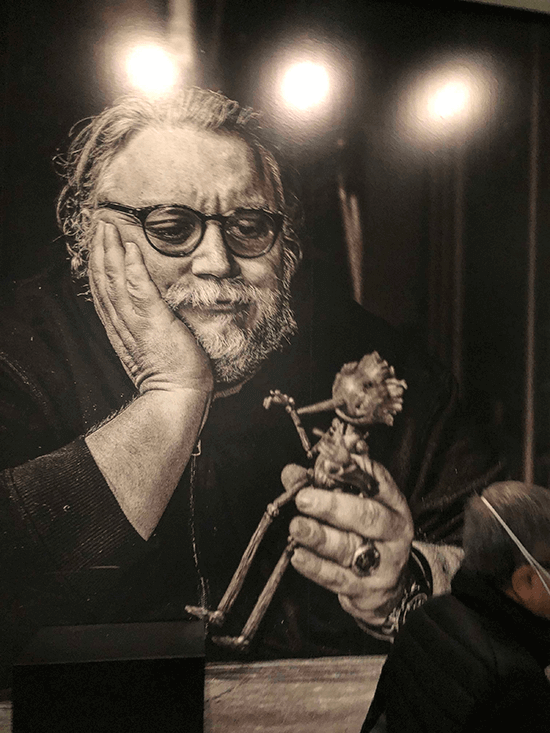

Del Toro plays Geppetto here. “Pinocchio has always been very close to my heart,” he says in an audio guide. One glass case simply shows handwritten notes charting the evolution of Pinocchio’s emotional life in the film, from birth to adulthood. We see the wooden puppet evolving from “Hope,” “Trust” and “Love” to “Confusion,” “Jealousy” and “Redemption.” Among the twists in the movie, Pinocchio doesn’t become an actual flesh-and-blood boy; he reaches actualization while still remaining a wooden being. “It’s a tale about becoming who you are, not transforming yourself for others,” the director says.

For Del Toro, even a classic allegorical children’s tale that was scrubbed up by Disney for its 1940 version can be a thing of unconscious mystery and deeper, darker meaning.

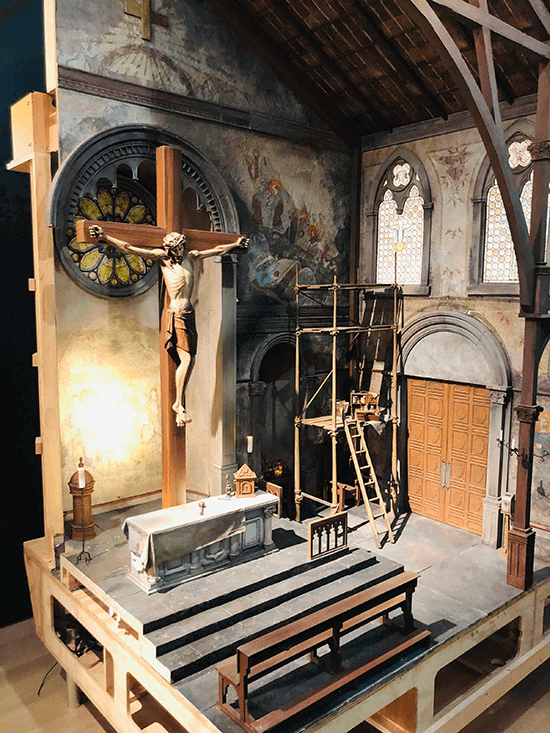

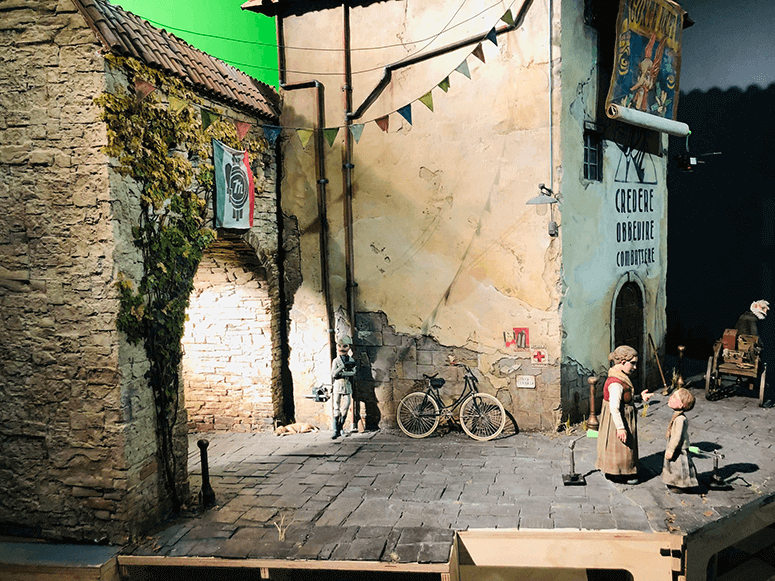

Another twist in the movie is the focus on Fascist-era Italy. Full-scale animation tables lay out key scenes, such as the boot camp battle between Italian boys, the church with its unfinished Christ sculpture, and Geppetto’s workshop, all of it lit stunningly.

There’s an eerie feel to seeing glass cases stuffed with handcrafted, 3D-printed marionettes, a number of them adorned in Fascist attire. For Del Toro, even a classic allegorical children’s tale that was scrubbed up by Disney for its 1940 version (itself still a stunningly emotional work) can be a thing of unconscious mystery and deeper, darker meaning. One line from the film is posted on a wall, hinting at a pervasive theme: “WHAT HAPPENS HAPPENS. AND THEN WE ARE GONE.” It sounds fatalistic, but it suggests the fleeting nature of time, something Pinocchio discovers through each of his deaths and rebirths.

The director thinks animation deserves more respect in cinema: “Animation is coming to a crucial point where we have to push it into being an art form—recognize it as cinema, not just a genre of fun.”

Certainly, Crafting Pinocchio shows us the serious intent behind animation that is itself art. In a way, it parallels Tim Burton’s exhaustive 2009 MoMA exhibit, cataloging his creative process through copious models, sketchbooks, and tableaus. Both directors share a deep sense of the macabre, as well as an underlying humanity.

But that’s not the whole show. Downstairs, more models (including a huge wooden-carved Pinocchio model hovering above) lead us to a basement that takes us behind the recording of Pinocchio’s orchestral score; a display of illustrated editions of Pinocchio from around the world sits opposite a cabinet of classic gothic horror novels (Frankenstein, The Raven, The Haunting of Hill House) with introductions written by Del Toro; even further downstairs, in the Yoshiko and Akio Morita Gallery, we glimpse an array of split-screen montages, some of Del Toro’s most resonant images—whether it’s the mechanical cockroaches of Cronos, his first film, or visions of Hellboy paired with Wesley Snipes in Blade II, or the reveal of Pale Man in Pan’s Labyrinth; Bradley Cooper wandering down Nightmare Alley, Sally Hawkins in a watery swoon from The Shape of Water, juxtaposed with the saturated reds of Jessica Chastain and Tom Hiddleston in Crimson Peak.

Missing here are Del Toro’s intricate notebooks kept over the years, with their ink-layered sketches detailing his most memorable characters— a seemingly endless supply of mythical, magical beings, dwellers in his own Nightmare Alley. Crafting Pinocchio is another look at the way those whispered dreams and scratches on paper, turn into resonant, meaningful art.