'An American Murder' review: A documentary chilling in its ordinariness

Chris Watts killed his wife Shannan, but you already knew that.

The trailer and graphics for Netflix’s latest buzzy true crime documentary, An American Murder: The Family Next Door, all but announce it. If you’ve followed similar cases, such as the 2002 Laci Peterson murder (by her husband, at eight months pregnant) or the infamous OJ Simpson trial (nearly decapitating Nicole Brown Simpson and Ron Goldman), you know: it’s the spouse. It’s always the spouse.

Told entirely through pictures and videos posted on social media by the late Shannan Watts, CCTV, courtroom and law enforcement footage, An American Murder initially hews so closely to true crime beats it brings to mind Gone Girl, which lovingly skewered the totemistic features of the genre. The tearful family conference. The worried best friend who sounds the alarm. The suspected spouse’s badly fumbled plea for his missing family “to just come home.” The detectives’ good ol’ cops routine. Even the suburban, majority Caucasian Colorado town where the Watts live call to mind the Missouri McMansions that Amy Dunne hated so much in David Fincher’s adaptation of the Gillian Flynn novel.

When the candlelight vigil pops up near the end of the documentary, it almost feels too on the nose.

Except Gone Girl was fiction, and the previously mentioned genre staples were meant to contrast with the big reveal that the wife planned it all along. One wishes that there was a similar twist to this story, but sadly there isn’t. Shannan Watts, as the film informs us in the end, is but one in a chilling statistic: every day, three women in America are killed by their partners.

Banality of evil

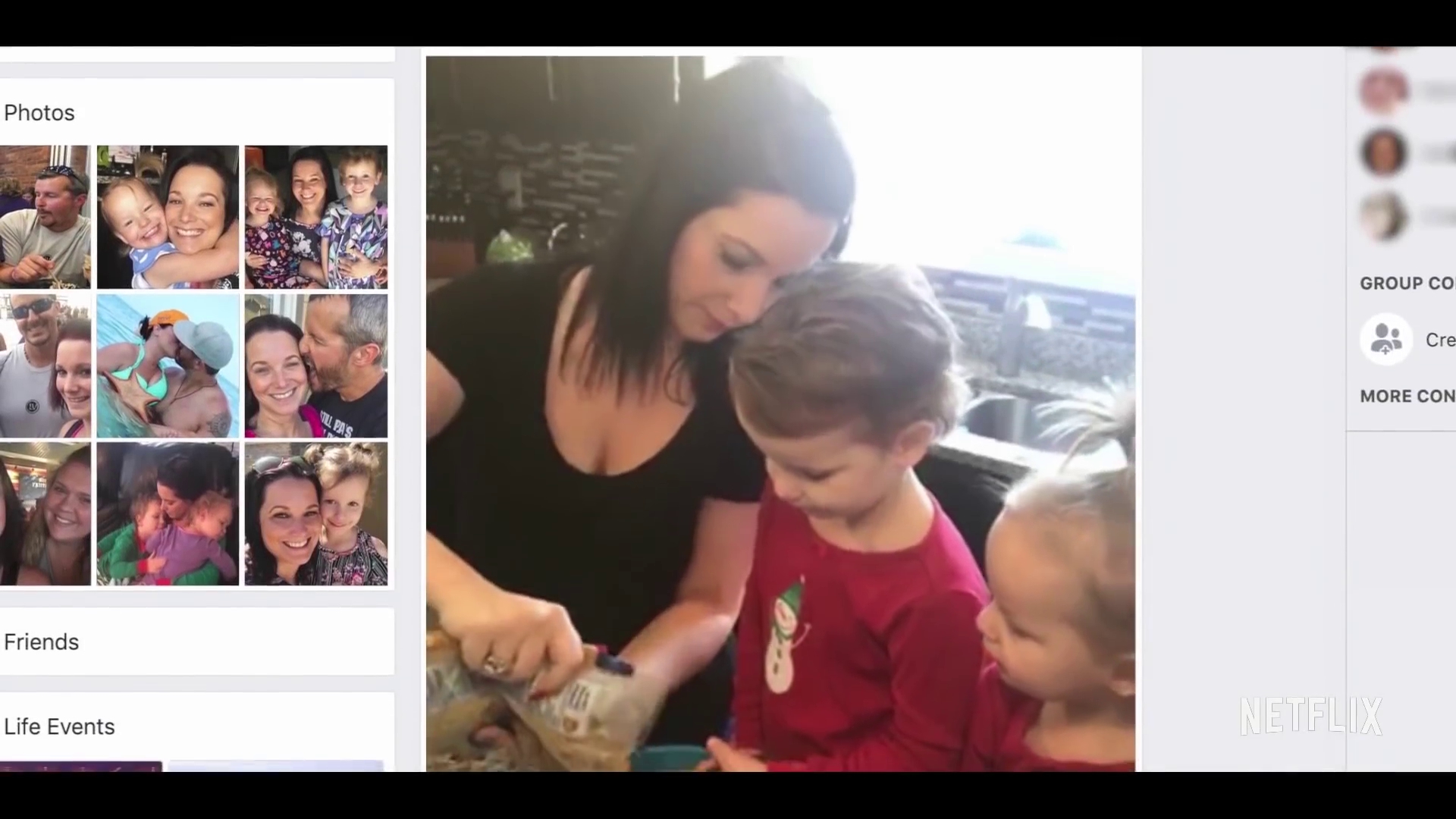

Where An American Murder succeeds in getting under the skin of the viewer lies in its very ordinariness. Like many millennial mothers, Shannan Watts diligently documented her family life online. The film abounds with videos of her and her gorgeous little girls, Bella and Cece. We see them at birthday parties, in an airplane, playing with their parents and grandparents. We see Shannan attempt to cleverly inform her husband of an upcoming pregnancy (via a Britney Spears-adjacent message t-shirt). And, in a hint of the marital troubles to be revealed in the course of the film, we see a low-level, passive aggressive argument between Shannan and Chris caught on video. It’s all so familiar.

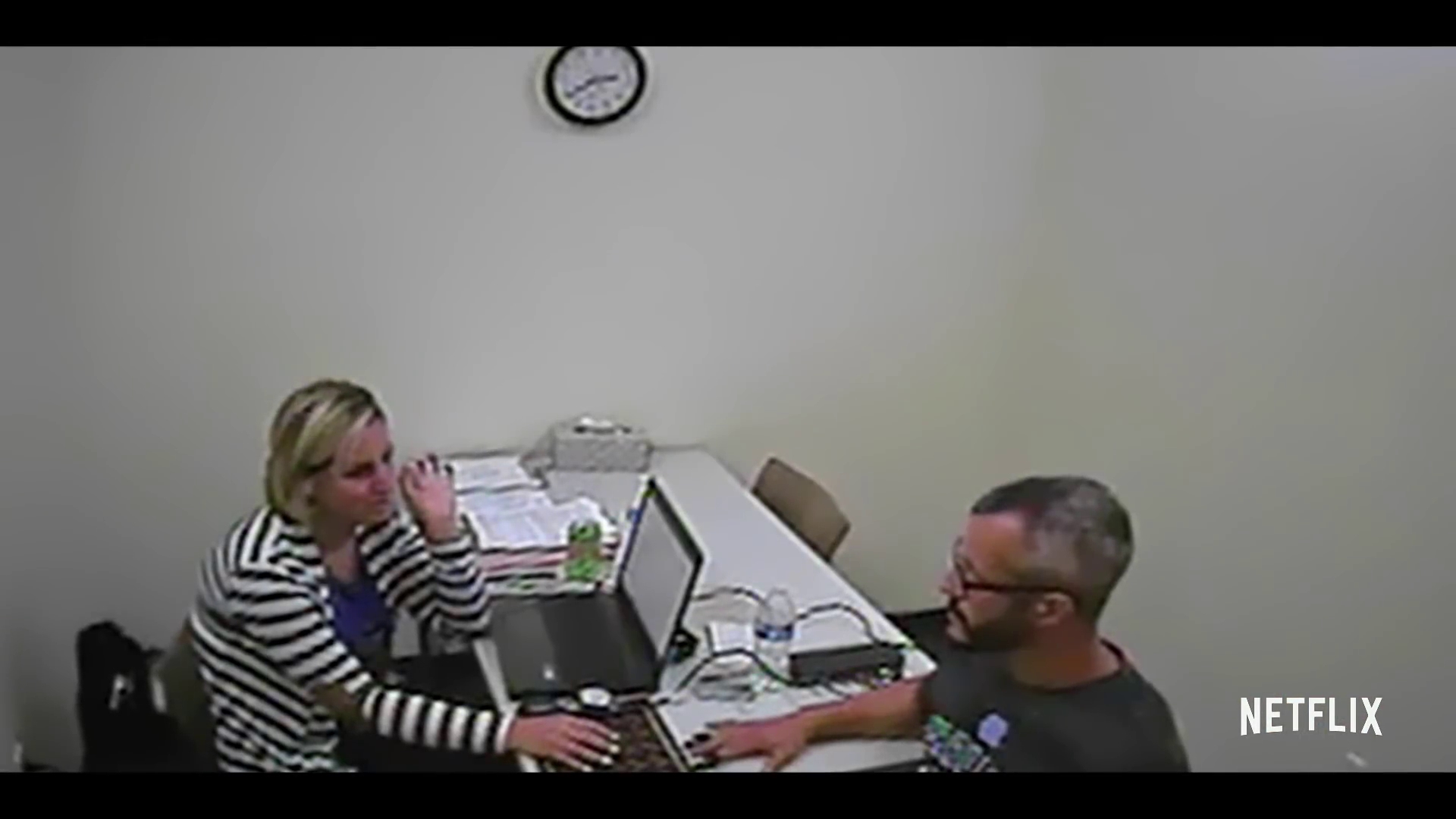

Then there’s the husband and suspect, Chris. Blandly handsome and buff with his salt-and-pepper hair, it’s almost comical to watch him fall for a detective’s flattery as he details his weight loss story. “245 pounds to 180? I gotta ask if someone inspired that,” the cop asks. Because there’s always a third party, and in this case, it’s his coworker Nichol Kessinger. She resembles Shannan so much she could have been her younger sister. The story she tells is also familiar from teleserye plots and maybe from gossip from your friends and relatives: “I knew he had kids. I knew he was married. He told me they were breaking up.”

The millennial mom, the cheating husband, the younger-version-of-the-wife mistress: it’s all so familiar, so ordinary; you might have encountered one if not all of them before. So why do the fates of these stock characters end so horrifically?

Because it is horrific, once Chris fails a lie detector test and gets so increasingly flustered by the questions of the detectives on the case that he calls for his father and confesses. He initially tries to do so in a half-assed way, to somehow make himself look less worse while casting aspersions on the wife he just admitted to murdering, but when the detectives – who clearly do not buy the wishy-washy confession – continue pressing him, the whole truth comes out, and it is ugly. The lead detectives on the case still have PTSD from recovering the bodies of Shannan and her children.

Throughout the documentary, via text messages that pop-up on screen between Shannan and Chris and Shannan and her friends, much is made of Chris being an avoider of conflict. The couple rarely fought, with Chris, in two instances in the film, choosing to work out instead of talking with his emotional wife. There is no inkling that this shifty, whining, seemingly detached husband might have been planning to kill her and his children all along, and the documentary does not explain his reasons why (a mercy, because the "how" was bad enough). When Hannah Arendt famously posited about the banality of evil, it isn’t hard to picture Chris, with his unimaginative tattoos and suburban dad gear, as its poster boy.

Which raises the question in the viewer’s mind: how many other detached spouses might be planning the same thing?

More questions

The documentary also raises two more questions that may or may not have been director Jenny Popplewell’s intent.

The first is a brief mention of the online tear-down of Shannan’s character during the initial media attention on the case. Voice snippets of women – unclear if it is taken from a recorded conversation or a TV show – argue that Shannan must have driven her husband to do it, while social media comments are flashed across the screen questioning Shannan’s parenting choices.

The choice of many online rubberneckers to blame the victim via her supposed wrongdoing against her spouse and her method of raising her children is alarming but not new. Examining that angle would’ve been a fascinating detour, thought it might have derailed the whole film.

The second touches on race and class. Much has been made on Twitter of Shannan’s best friend, Nickole Atkinson, rushing to Shannan’s house seven hours after dropping her off from an out of town work trip. Nickole is so disturbed by Shannan not replying to texts that she calls the police, who immediately dispatch an officer to the scene.

Given the recent and frequent reports of people of color being dismissed by law enforcement for reporting more serious concerns... one wonders if the case would have been so quickly resolved if the victim were not white and affluent.

The officer arriving so promptly mere hours after Chris has been out dumping bodies is one of the reasons why his shifty behavior is immediately marked as suspicious, and helps the detectives in the questioning that ultimately leads to his confession.

Given the recent and frequent reports of people of color being dismissed by law enforcement for reporting more serious concerns, or stories of victims from a lower social class "falling through the net" of red flags that should’ve been noted, or even of the familiar TV/film trope of a world-weary officer telling a distraught citizen that “we can only start a missing persons investigation 48 hours after a person has been reported gone,” one wonders if the case would have been so quickly resolved if the victim were not white and affluent. A quick Google search will show it’s not likely.

An American Murder: The Family Next Door is equal parts infuriating and chilling. I certainly am sleeping with one eye open tonight.

(Image screenshots from An American Murder: The Family Next Door)