Pages from the past

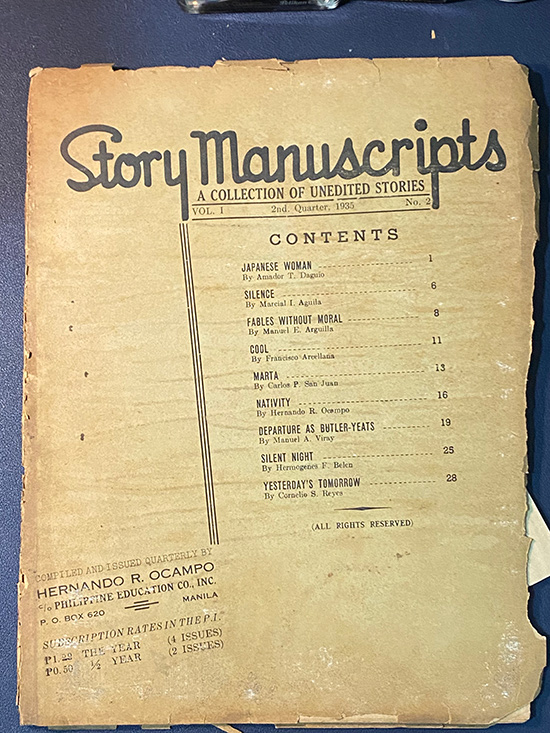

Last month, two precious documents came my way. The first was a magazine with a unique idea behind it. It was a copy of Story Manuscripts, “a collection of unedited stories,” Vol. 1, No. 2, from February 1935. No more than mimeographed copies of the authors’ typewritten manuscripts between two hard covers, this issue brought together stories from Amador Daguio, Manuel Arguilla, Francisco Arcellana, Manuel Viray, and H. R. Ocampo, among others.

Ocampo’s presence was especially interesting. I knew that National Artist Hernando Ruiz Ocampo (1911-1978) was a short story writer before he turned to painting, but he was this magazine’s publisher as well. What was exciting for me (as a writer and literary editor, especially of Arguilla) is that I’d never come across these stories before under these titles, so they’re very likely undiscovered stories or early drafts of later ones, being “unedited,” as the Story Manuscripts tagline claims.

Arguilla’s three “Fables Without Moral” — I have to check if they appeared in the book of fables that his wife Lyd published after his death and credited him for as co-author — are a surprise. They all have to do with, uhm, procreation, rendered in a mock-mythic tone. I would have to revise my introduction to the Arguilla anthology I edited three years ago to account for these risqué diversions.

Here’s a sample:

“But soon he awoke for an earthquake shook his newly-found home and a storm tossed the forest of hair and a groaning and moaning filled the air. Then a downpour such as he had never before known drenched him, buried him in its thick flood.” (Hint: “he” is a vagabond ant.)

The Arcellana story, “Cool,” is quintessentially Franz — the young and ardent admirer (the author himself was just 18 then) watching his beloved from a distance, chanting over and over again, “I see her but I do not want to see her looking at me.”

H.R. Ocampo’s “Nativity” is, unsurprisingly, visual: “The big round eye floated gently upward and upward. Then it ceased floating upward. It ceased floating and winging upward and was suspended in space. Then it was dark. Darkness all around. Darkness for a brief one millionth second.

“After the brief one millionth second the big round eye came back seeing everything and nothing in a whirling sphere of soft jelly-like mass of white and black and red and green and orange and blue and violet.”

There’s an interesting biographical footnote to the Ocampo story: “Hernando R. Ocampo was born on April 28, 1911 in Sta. Cruz, Manila. Began writing two years ago on a dare and thought that writing was ‘just like that’ when his first effort was immediately accepted by Mr. A.V.H. Hartendorp of the PHILIPPINE MAGAZINE, but a series of rejection slips from the same and other local editors later toned down his ultra-optimistic viewpoint — so much so that he actually considered giving up writing ‘for good.’ Fortunately he met Manuel E. Arguilla who through patient coaching gave him courage to try anew.”

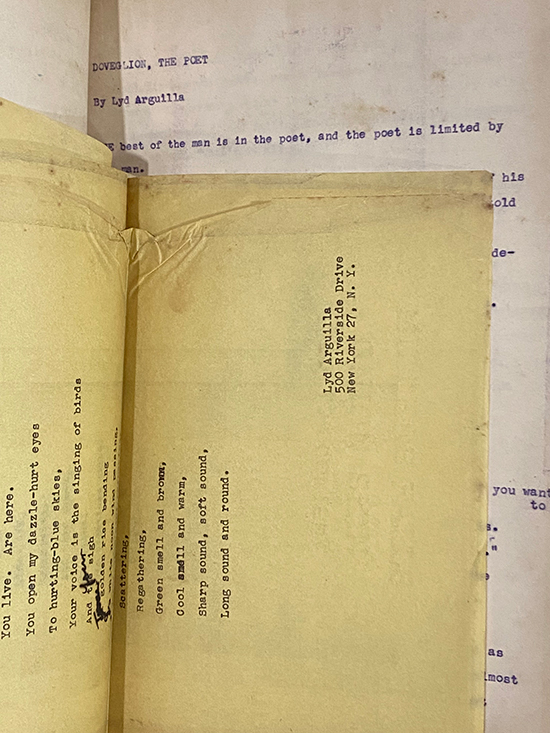

The other document I felt extremely lucky to acquire was a plain black folder, rather worn, with about 60 to 70 pages in it of what was obviously a carbon paper copy. It was also clear, however, that the author of these pages had used this copy to make handwritten revisions on.

Arguilla was accused of being a major in Marking’s guerrillas, of heading an espionage and propaganda unit against the Japanese. Liling (Rafael R.) Roces was charged with publishing Free Philippines and various other acts against the Japanese military.

It was a collection of essays written by — and I’m not sure if they were ever published — during a sojourn to the United States in the early 1950s, when she received a grant for further studies in New York. This was just a few years after the war; in 1944, she had lost her husband Manuel, who was executed by the Japanese for his guerrilla activities.

Lyd had been active in the resistance herself, and was away when Manuel was arrested. We can only imagine the pain she went through on discovering his loss. By the time she writes about the experience, she has composed herself, but she leaves it to Manuel’s fellow prisoner, a Major Moran, to relate what happened:

“On a tip from Pete Mabanta, Manuel E. Arguilla had already escaped with us out of the city. Friends and fellow members of our guerrilla unit had helped: the Lansang brothers, Ramon Estela, S.P. and Mary Lopez, Koko and Lina Trinidad. But Manuel sneaked back into the city to destroy or put in a safer place some records. He was able to protect the lives of his associates, but did not escape with his own.“‘Arguilla was accused of being a major in Marking’s guerrillas, of heading an espionage and propaganda unit against the Japanese. Liling (Rafael R.) Roces was charged with publishing Free Philippines and various other acts against the Japanese military.’

“‘Arguilla had enough material, according to him, for two books. All he asked was to be able to live through to write them.

"'It was on August 29th, early in the morning, about seven o’clock, maybe earlier, that the prisoners in Bilibid were given old clothes to put on (we all wore our underwear), put in handcuffs, and blindfolded. The blindfold was either green or white. The 28 men wore white bands. I thought, being most of them influential men that they would be given better treatment than those of us who were given green bands. I was wrong of course. For I and others were taken to Muntinlupa where we were finally liberated, and the 28, as we learned later, were beheaded at the Chinese cemetery.’

I could imagine Lyd typing those words on a chilly morning in New York and running that awful moment through her imagination. Elsewhere in the folder, she tucked away a love poem she had written for Manuel. Holding those pages, I felt myself in the presence of something close to sacred.