The man who wrote ‘Citizen Kane’

It certainly helps to have some working knowledge of Old Hollywood lore, Orson Welles or Citizen Kane to thoroughly enjoy Mank, shown on Netflix. But for this effort, you will be richly rewarded: you can groove on David Fincher’s noir California desert compositions (shot by Erik Messerschmidt), the witty interplay between screenwriters like Herman J. Mankiewicz (played with gusto by Gary Oldman), Ben Hecht, George S. Kaufman and Upton Sinclair, or the power plays of MGM head Louis B. Mayer, Irving Thalberg and newspaper mogul William Randolph Hearst (Charles Dance), without having to constantly ask “Who’s that?” or “What’s going on?”

Even if you’ve only ever half-watched Citizen Kane, Welles’ 24-year-old wunderkind directorial debut, you know about “Rosebud” and Xanadu, that huge California mansion stocked with exotic wildlife and priceless treasures; you may even know about Hearst’s mistress, Marion Davies (here played by Amanda Seyfried) and how she plays into the story.

But the cool part of Mank is how it pulls its focus back from the actual nuts and bolts of Mankiewicz’s Oscar-winning script for Citizen Kane (his only win, co-credited to Welles, who wrote virtually none of its sharp, world-weary dialogue), in order to take in so much more: the humanistic impulses of Mank himself, or the contrast between the obscenely rich (here mostly depicted as Hollywood moguls and career Republicans), versus the downtrodden, socialist tendencies of writers like Sinclair, set against the Great Depression.

Mank himself was a classic Hollywood underdog: a script doctor who labored without screen credit to whip scripts like The Wizard of Oz and The Front Page into diamond-like shape. Hearst reportedly let him hang around the mansion because of his lively wit, drunken or otherwise.

The script for Manx was actually penned by Fincher’s late father, Jack, long ago; and it is talky — but such entertaining talk. (A classic scene: Mank drunkenly laying out his plans to adapt Don Quixote for the screen, starring Hearst, Mayer and Davies, in front of increasingly unsettled dinner guests.) Don’t miss Lily Collins (Emily in Paris) as Mank’s sympathetic nurse, Rita; or the fleeting glimpses of Welles (Tom Burke), shot in a Mephistophelean cloud of cigar smoke or noir shadows. Or just sit and enjoy Oldman in full glory, having a great time playing a drunk, a genius, and a damn fine writer who knows perhaps a little too much about Hollywood for his own good.

Because Hollywood is the real story here — just in time for Oscar bait season, such as it is — and this one has all the nasty holiday trimmings.

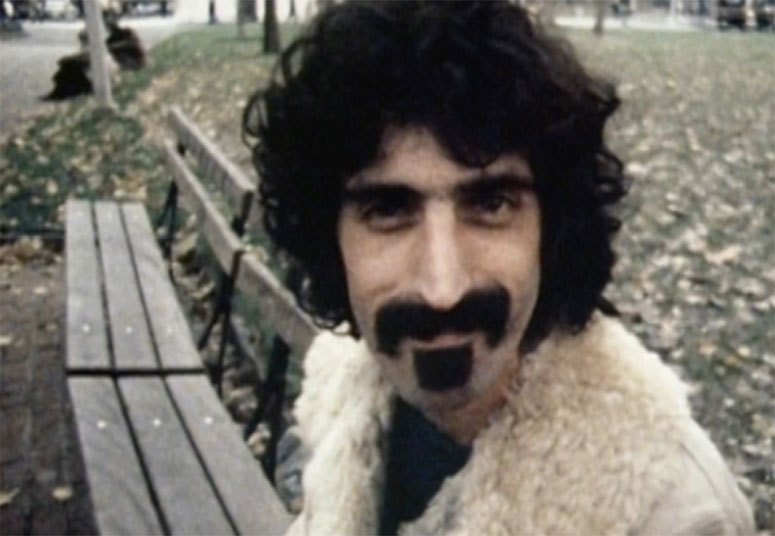

THE EXCENTRIFUGAL FORCE OF FRANK ZAPPA

Zappa is a fan’s movie. Alex Winter (half of Bill & Ted, and director of this documentary) is a fan, and that’s why he got access to a treasure trove of Frank Zappa home footage, concert bits, and later interviews that prove he was more than just the “Don’t Eat the Yellow Snow” guy.

Zappa assumes you know the guy’s catalogue already, but for me, it was a greater revelation to hear that his later, orchestral music now sounds more appealing and enduring, even, than a lot of the earlier eccentric fusion he whipped up with his series of tight touring bands.

We learn about Zappa’s early frenzy of film editing and music composing as a boy, driven by Edgar Varèse to atonal structure; how he formed one of the first racially integrated bands in Cucamonga, California to great acclaim and misunderstanding. The Laurel Canyon freaks and SNL cast members thought he was a druggie like them (he wasn’t, he abstained), while most casual fans preferred his sillier stuff like Bobby Brown or Nanook Rubs It.

Zappa didn’t care. He just kept going, from composition to composition, tour to tour (from The Mothers to Flo & Eddie to the George Duke and Steve Vai years), always attracting more respect than, perhaps, understanding and appreciation. (The live footage sprinkled throughout is worth the price of admission alone.)

Winter’s movie also focuses on unlikely champions — Prague president Vaclav Havel, and anti-censorship advocates during his testimony about “obscenity” in music before the Senate — and it doesn’t shy away from discussing Zappa’s groupie affairs while touring constantly, and the effect it had on his family. (His daughter had to slyly pitch her idea for a new song, Valley Girl, by pinning a note to her dad’s door: “Hi! I’m 13 years old. My name is Moon. Up until now I’ve been trying to stay out of your way while you record…”) Like his own kids, Zappa’s musicians learned to take the good with the bad, and while they generally concede their boss could be a hardcore a-hole at times, they all respected his artistic integrity. Put that on your epitaph and smoke it.