Pure intentions and unexpected outcomes

Let’s start with the bollard. When the curators of “Pure Intention,” the 2025 iteration of Singapore Biennale, wanted to place one installation near a massive 600 kg hunk of steel that secures boats to the Tanjong Pagar port, they got bureaucratic pushback. So instead, co-curator Selene Yap tells us, they asked to move the bollard inside Singapore Art Museum—aka SAM—as an entry point to the main gallery. Despite concerns it would collapse the ground floor. But there it sits now, symbolically demarcating the point between land, and that which is far adrift.

It’s an apt symbol for “Pure Intention.” In art, pure intention is a term connected to direct personal expression, a gesture wielded with clarity and purpose. The term nicely connects to Singapore’s carefully sculpted cityscapes and future-planning. In response, by overlaying site installations in unexpected pockets of the city, “Pure Intention” both pays tribute to that 60-year history and initiates fresh dialogues.

Yap describes those dialogues as “intention and afterlife.” “Singapore is built on intention,” she tells us, walking us through SAM’s main gallery. “Life is defined by the gaps in the city.” Like that bollard, now borrowed for art.

From now until March 29, 2026, “Pure Intention,” devised by SAM’s “curatorial network” of Yap, Hsu Fang-Tze, Ong Puay Khim and Duncan Bass, offers reimaginings of Singapore’s history, the city shot through with alternate realities, parallel narratives below the surface; reflective, and often whimsical.

Mind the gaps.

Deploying the surprise

At Tanglin Halt, a public housing estate with its block of hawker stalls, shophouses and snack stops, you settle into a dimly lit, cool-looking space, thinking it’s a café. You set down on plastic stools next to tables set up with plastic pitchers of water and cups; nearby, one table is overturned, a sign of upheaval. And on a big screen loops a reimagined HK soap opera created by Adrian Wong. The installation “With Hate from Hong Kong” recreates the nostalgia and grainy VHS texture of imported TV dramas, but flips the script: the men onscreen are cowering, subservient; the matriarch is an evil plotter. Yap tells us how gratifying it is to see curious passersby come in, thinking it’s a real snack place, settling down and wondering where the staff are, and what the hell is going on.

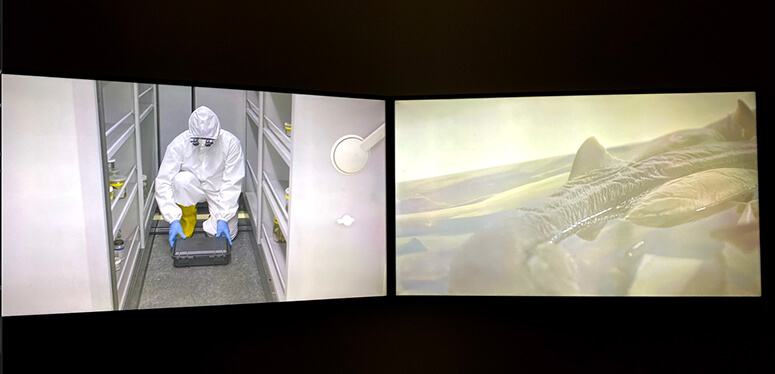

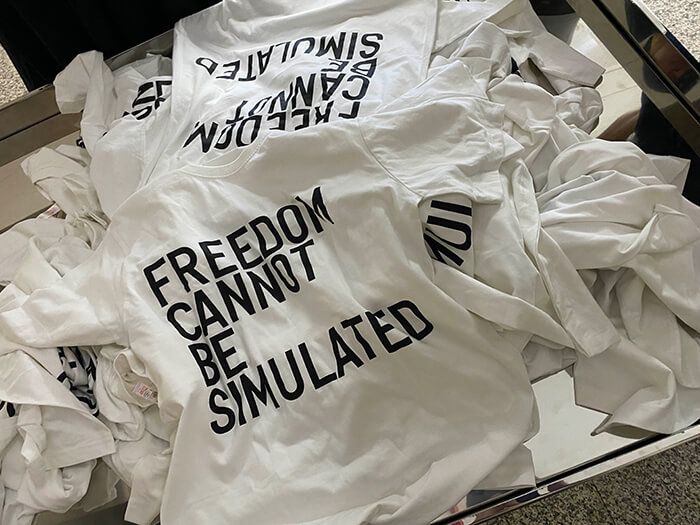

Many artworks play with expected realities. At Rail Corridor, Java artist Rizki Lazuardi’s “Operation Thunder Tooth” deploys elaborate pseudo-historical relics of a discovered megaladon (ancient shark) tooth, interweaving a plot involving the CIA in split-screen video that blends found footage and fiction. It feels like a museum exhibit. A film slide projector in a corner hints at authenticity, material evidence, provenance.

So what do we believe? And is pranking the most effective vehicle for artistic expression in an age where reality itself is in question constantly?

Everywhere, the notion of consumption is inserted at odd angles, like the palette of cardboard boxes on SAM’s loading dock—“Metabolic Container”—created by collective CAMP, mingling real and imaginary Indonesian food products (“SHINY RED BUTTER”) with metaphysical messages (“EQUAL EXPOSURE… LESS OIL”); meanwhile, at SAM’s Sip Café, a scaly dinosaur claw proffers a Milo Dinosaur, part of the collective RRD’s “Gastrogeography: Stories from Mexico to Singapore” installation which traces food habits along trans-global trade routes through Asia. And at several sites, vending machines offer Huang Po-Chih’s (Taiwan) “Momocha,” an actual brewed kombucha drink that’s part of the artist’s ongoing social experiment project: integrating artworld resources into real-world agricultural economies, using cash crops from his home province, in “an entanglement of agriculture, migration and memory.”

Locational context is everything

As co-curators Hsu Fang-Tze and Ong Puay Khim remind us, historical context is key to every site location. Care is taken in deploying these pieces in public spaces. “Our first audience is always our own neighbors,” notes Khim. Besides Rail Corridor, with its association of public housing and forgotten places mingled with surprises (like the painted tiles by artist Jesse Jones paralleling long-gone railroad tracks), there are visits to nearly forgotten malls amidst Singapore’s high-rise, master-planned Orchard Road.

We step inside Lucky Plaza, known as a mecca for Filipino migrant workers, especially on Sundays, their “day-off.” That’s when you’ll see most Filipinos gather there, to pick up Lucky Me, Nova Chips or Skyflakes from vendors, to wire money home, or to simply laugh and find strength among their own. With a city mandate that allows commercial self-direction, Lucky Plaza remains an ethnic enclave that provides domestic abuse help desks, legal aid and other vital community services to Filipino, Burmese, Indonesian and Thai workers. Aesthetically, it reminds you of labyrinthine malls like Shoppesville and Makati Cinema Square from the ‘90s.

And that feeling of nostalgic comfort is the point. Here you’ll find Eisa Jocson’s safe space for Filipino and other women, who wander into a Pinoy sala, complete with flower-pattern curtains, stuffed sofas and monobloc chairs. Microphones on the table invite you to join in on the karaoke jam. This is “The Filipino Superwoman x H.O.M.E. Karaoke Living Room,” part of Jocson’s commentary on OFW kinship and empowerment (a live performance is planned for Singapore Art Week next year). The array of family photos, the Journey ballads and OPM songs mingle with uploaded videos from the community, giving the space a poignant, homegrown resonance.

Elsewhere in Far East Shopping Centre, the usual health clinics and law services are disrupted by nostalgic callbacks: the ‘90s, Fang tells us, was a defining time for Singapore’s vault into hyper real estate status. The boom led to “a certain gray dichotomy or tension,” the old remaining malls offering “a strong time capsule of past-present.” “People don’t come in unless they need a certain thing or service,” Fang remarks. “There’s a reflecting on what exactly is the capitalism machine? How far can this run and what will be the result when a specific modality dies out?”

What could be more disruptive to that upward vision than an ancient net café? The kind with crummy carpeting, plastic tables and PCs showing “YouSurp” videos with titles like “shark attack on cable” and “dead internet theory is real now”? Sri Lanka collective The Packet’s installation “Water Under the Bridge/A Bridge Under Water” reminds Singapore of the ghosts in the machine: “Water has memory, everything has memory and everything is drowning,” reads the web browser. “Dive into the internet’s subconscious, it’s wet, electric, and just a little haunted...”

Speaking of haunted, on Oct. 31 we stopped by Raffles Girl’s School, a now-deserted site that was Singapore’s first institution to accept female students under colonial times—an outrageous idea back then. Since relocated, the site is now known simply as 20 Anderson Road—a campus of empty classrooms, quads and deserted corridors—a perfect place for installations that can feel spooky, even if their intention is to raise awareness on climate disaster or explore the connections between science and spiritualism. Many of the Biennale exhibits here dance with the macabre. An abandoned band practice room is decked out with Ozgür Kar’s skeleton-animated instrument cases (“Death with Clarinet, Flute, and Little Bell”) twiddling out dissonant diabolus in musica trichords. Elsewhere, Riar Rizaldi’s “Mirage: Agape” airs a video exploring the Sufi idea of emanation through a sword-and-sandals TV drama as an animatronic decapitated head eerily shares the stage.

Japanese/Indonesian artist Kei Imazu’s triptych of large-scale paintings reimagines the brown goddess Hainuwele, known for producing objects of wealth, food, fruits, who was chopped up by male leaders due to her ability to manifest abundance. In “Memories of Land/Body,” the artist looks at female autonomy and how it connects with her own process of giving birth, weaving in visions of nature, Indonesian tigers, birth canals, placenta—and, yes, that is Rihanna’s profile inserted into the sprawling main canvas.

And who knew Owner of a Lonely Heart could feel so spooky? Slowed down to half-speed, the ‘80s Yes song is paired with Yuyan Wang’s “Green Grey Black Brown” video exploring the churning global impact of petroleum products on our planet. (Yes, the real scary stuff is what we’re doing to ourselves.)

‘A collectively altered chaos’

As curators, the process of “Pure Intention” was to view Singapore as “a collectively altered chaos.” There were always unexpected results, Khim notes: “Even as artists come, they may respond differently to what we thought they might do, preferably. So it’s this whole process of thinking about topology of spaces and responding to artists as well.”

Duncan adds, “Everyone has an image of what Singapore is. I think the goal was to challenge that image, to complicate it a little bit and to show that there’s a bit more like paradox within that kind of clean, sleek image of Singapore.”

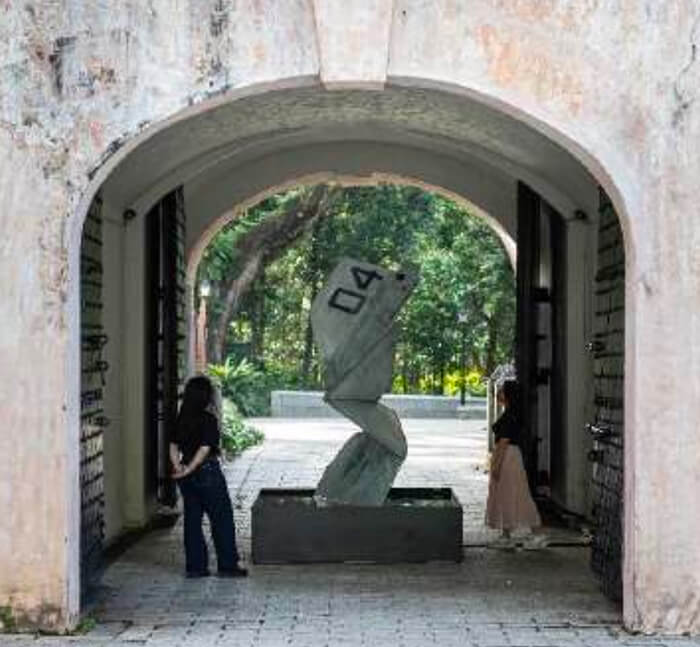

In Fort Canning, with its colonial history, public art literally cries out. Jacqueline Kiyomi Gork’s commissioned “HNZF IV” stands for “High Noise Zen Fountain,” and wanderers in the bucolic park are first entranced by the trickling sounds of a water fountain, atop which sits sculpted military scrap from a WW2 fighter jet; the soothing feeling is soon replaced by a grinding cacophony from the amplified audio feeds placed in the water.

Your phone guides you through another audio journey, Taiwan artist lololol’s “Light Keeper” installation, by scanning a GPS-enabled QR code. Foghorn and wind sounds merge with poetic musings on the century-old Fort Canning lighthouse itself, no longer facing out to open harbor, but rather a dense city built on reclaimed land. The artist’s accompanying video, inside Fort Canning Centre, poetically explores the relation of a lighthouse keeper to technology, to nature, and to a place where “memory continues to multiply at the bottom of boundless seas.”

* * *

Commissioned by the National Arts Council Singapore, supported by the Ministry of Culture, Community and Youth (MCCY), and organized by the Singapore Art Museum as the SG60 Signature Event, Singapore Biennale 2025 spans five key locations—the historic Civic District, lush Wessex Estate, iconic Tanglin Halt, bustling Orchard Road, and SAM at Tanjong Pagar Distripark—and runs until March 29, 2026. For ticketing and other information, including full list of artists, artworks and programs, visit www.singaporebiennale.org.