From poetry to treason

As a collector of old books and other objects of interest more ancient than me, I sometimes stumble across manuscripts and documents that turn out to be a bit more private than the usual accounts of travels to Sulu or the history of Negros sugar.

I’ve found ardent and very carefully composed love letters (apparently never sent), poems to the departed, and receipts for unmentionables.

Coming from a past where people wrote with physical ink on physical paper, these inadvertent mementoes of lives lived and loves lost convey emotion and meaning in a way that digital ones and zeroes never will.

Some of these discoveries have been particularly poignant. A few months ago, I wrote about finding a typewritten collection of essays written by Lyd Arguilla in the 1950s, where she stoically recounts her husband Manuel’s execution by the Japanese; tucked into that folder was a love poem she wrote in his memory after the war, in New York.

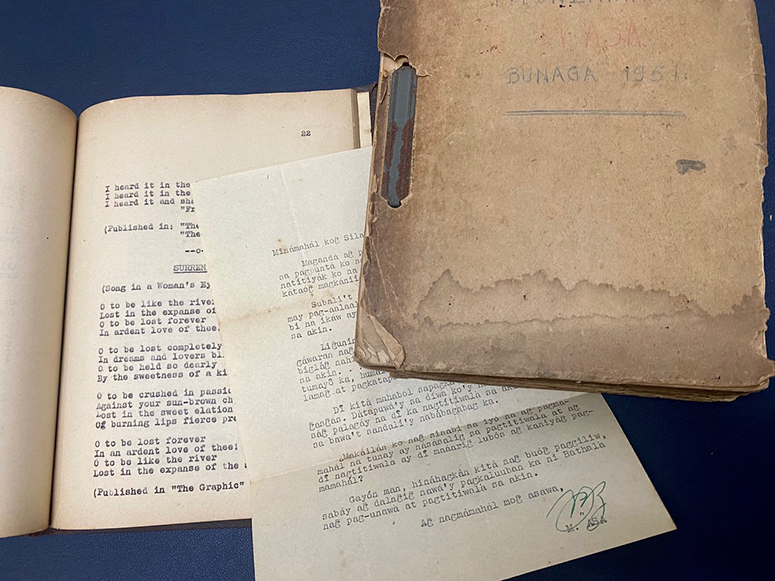

Last month, a bookseller offered me three items that had to do with one subject, from whose personal library they likely came.

One was a scrapbook of sorts by this Filipino author, another a short biography — also typewritten — of the man and samples of his most popular works, and the third a published play written by his illustrious mother.

The writer’s name was vaguely familiar to me: Aurelio S. Alvero, otherwise known by the pseudonym he adopted after the war, “Magtanggol Asa” (he himself spelled it “Magtanggul”), a play on his initials and on his ambition to become a lawyer — as well as being, of course, a self-descriptive epithet as the defender of hope.

He was born in 1913 in Tondo to illustrious parents — Emilio Alvero, an artist and interior decorator, and Rosa Sevilla, writer, suffragette, and educator who founded the Instituto de Mujeres, a pioneering school for women in the Philippines.

Generations of Filipino schoolchildren have known him for his poem “1896,” written before the war, a favorite piece for choruses, because of its hypnotic rhythm and refrain. It begins:

The cry awoke Balintawak

And the echoes answered back…

“Freedom!”

All the four winds listened long

To the shrieking of that song….

“Freedom!”

Just by this piece, no one can be faulted for thinking of Alvero as a patriotic poet — or in the very least a writer of patriotic poetry, and that he was.

Indeed he was lauded by his peers and even later by scholars such as Grant Goodman and Augusto de Viana as a “brilliant” intellectual, one who could write equally well in Tagalog, English, and Spanish. He was a star student at the Ateneo and UST, winning a raft of medals for his scholastic achievements.

But he was also described as a “complex” artist, a rather evasive and much kinder term for what his harshest critics would call him: a traitor to his people, convicted and imprisoned for wartime collaboration with the Japanese.

How could the same man, so gifted and so promising, turn out so badly? Even before the war, Alvero had railed against American imperialism, and — like Gen. Artemio Ricarte, among others — saw Japan as a friend and liberator.

The charges brought up against him by the postwar court were formidable: up to 22 counts of treason, from his active role in such pro-Japanese organizations as the Kalibapi and Makapili to selling war materiel to the enemy and participating in the destruction of Manila.

The most outrageous offenses were damnably detailed: among them, that within one year, his trading firm — capitalized at only P15,000 — earned a whopping P2,000,000 from sales to the Japanese (shades of Pharmally!), and that he personally directed the burning of a part of Pasay toward the end of the war.

For these, and despite his spirited protestations, he was sentenced to life imprisonment in Bilibid, cut short by an amnesty granted by President Quirino in 1952.

How could the same man, so gifted and so promising, turn out so badly? Even before the war, Alvero had railed against American imperialism, and — like Gen. Artemio Ricarte, among others — saw Japan as a friend and liberator.

But unlike more rabid pro-Japanese Filipinos like Benigno Ramos, he opposed the atrocities of the Makapili, although he urged his countrymen to resist the Americans to the end. Complex indeed.

Arguing that neither “patriot” nor “traitor” could fairly describe him, Dr. Goodman calls him “a romantic opportunist” who thought he could achieve his ideals by casting his lot with the devil.

Despite his early release from prison, the ordeal took its toll. While other writers accused of helping the Japanese like Camilo Osias lived on and even prospered, Alvero died of a heart attack in 1958 aged just 44, leaving a stain on his family’s name (his mother, Rosa Alvero, continues to be honored with a street in her name in Katipunan, Quezon City). Hardly any pictures of him can be found today, even on the Internet.

A letter from prison to his second wife, whom he called “Silahis,” reveals an inner torment that was probably the greatest cost of all.

He writes:

“Makailan ko nang sinabi sa iyo na ang pagmamahal na tunay ay nasasalig sa pagtitiwala at ang di nagtitiwala ay di maaring lubos ang kaniyang pagmamahal? Gayon man, hinahagkan kita nang buong paggiliw, sabay ang dalanging nawa’y pagkaluuban ka ni Bathala ng pag-uunawa at pagtitiwala sa akin. Ang nagmamahal mong asawa, M. Asa.”

(How often have I told you that true love depends on trust, and that one who cannot trust cannot love completely? Nonetheless, I kiss you with all my heart, even as I pray that the Lord grant you trust and understanding for me. Your loving husband, M. Asa.)