Jim Thompson: A legacy of silk and a house of art

Who would think that a man dressed in silk fineries and sequins would define a new image of sartorial elegance and help launch the Thai silk industry in the world market? Of course, you have to be as hot as Yul Brynner playing the dashing monarch in The King and I, a 1956 film based on the novel Anna and the King of Siam.

The silk also had to be Jim Thompson, the powerhouse named after the man who revitalized a national craft and gave it international appeal. Thompson, in fact, also reached a level of fame not unlike the Hollywood star, so that when he mysteriously disappeared on a holiday in the forest highlands of Malaysia in 1967, more than 500 people were involved in the search party which, aside from the army and the police, included Orang Asli trekkers, Gurkhas, reward hunters, scouts, mystics, missionaries, residents and even tourists and other adventure seekers.

Thompson grew up in Greenville, Delaware, where he was born in 1906 to a textile manufacturer father and a mother with a military lineage. In 1931 he worked as an architect in New York, designing houses for the East Coast elite until 1941, when he joined the National Guard and later the OSS, the forerunner of the CIA. The job landed him in Thailand, where he organized the Bangkok office.

By 1946, he headed back to the US to seek his discharge from the army so that he could return to Thailand as a businessman, joining a group of investors to buy the Oriental Hotel. While working on its restoration, he could not agree with his associates, prompting him to sell his shares. The loss of the Oriental, however, would be the gain of the silk industry, since his love of Thai art and heritage would take him around the country’s villages, where he discovered splendid, hand-woven silk, a product utilizing skills that were vanishing in the aftermath of war and the influx of machine-made versions.

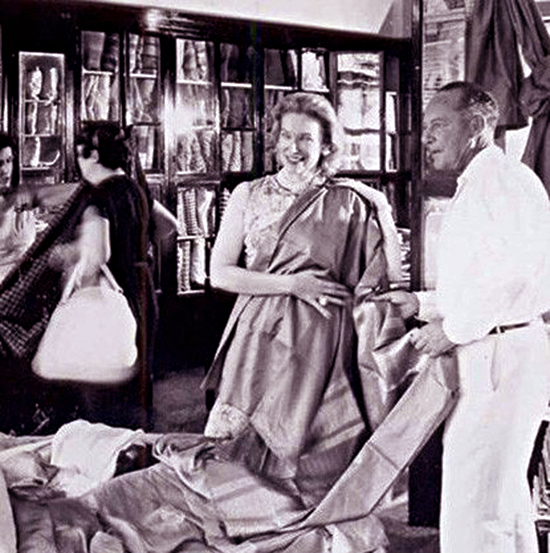

After studying silk in the National Museum, he commissioned pieces from weavers and co-founded the Thai Silk Company in 1948. Creating intricate patterns and vibrant colors, he came up with a luxurious product that would find a market in America through his contact with Vogue editor Edna Woolman Chase. It wasn’t long after the magazine feature that his fabrics would be chosen by Irene Sharaff to dress Brynner’s King Mongkut, his 80 children and their governess in the landmark film. It was the turning point that would bring Thompson wealth and fame, bringing buyers from all over the world to his shop and attracting celebrities like Truman Capote, Barbara Hutton, Doris Duke, Edward Luce, Cecil Beaton and the Kennedys. Queen Sirikit would make the silk even more popular when she asked Pierre Balmain to use it to make her couture wardrobe.

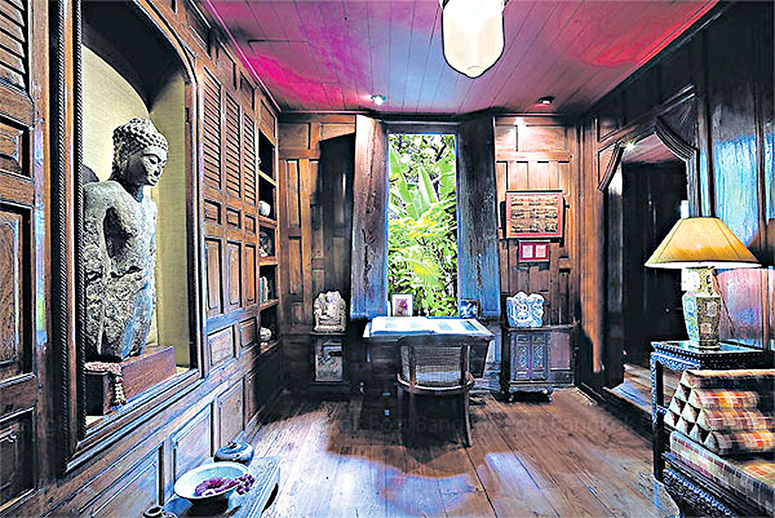

His success would allow him to indulge his passion for art to the fullest, acquiring an immense collection of rare, fine pieces of Buddhist sculptures, paintings, porcelain and objets d’art from Thailand and Southeast Asia. By 1959, it would also enable him to build his dream house, which would become a national treasure and his enduring legacy.

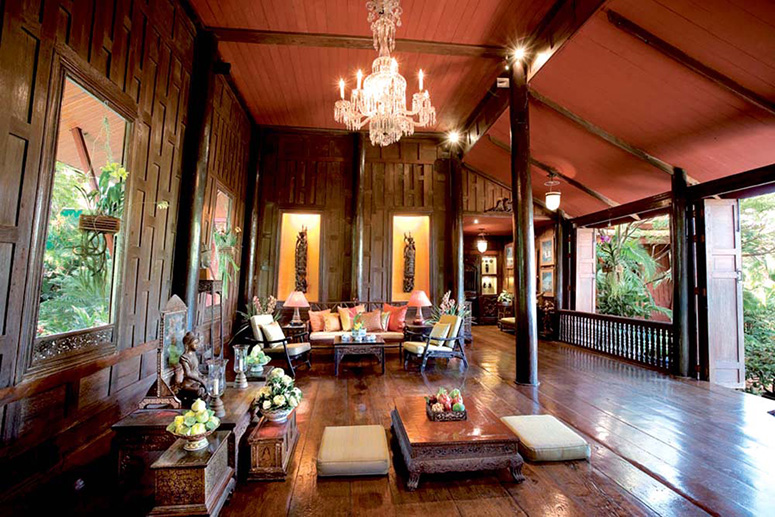

Actually, it was made from six traditional Thai houses in teak, which he sourced from Ayutthaya and Banh Krua, many over a century old and one dating to 1800. He saw the beauty in them when most people would rather live in new, Western-style dwellings. Ideal for the tropics, these houses are on stilts to protect from flooding, have open verandas and high, steeply sloping roofs for ventilation. Assembled without nails, the house has walls fitted and hung on wooden pillars to make them easy to knock down and reassemble in case the family has to move. Doors have high thresholds to hold the walls together and keep babies from falling off the house.

Interconnecting these houses with walkways, Thompson created a unique complex on a half-acre plot situated along the Maha Nak canal in Old Bangkok, easily accessible to the weavers and various traders with whom he built his silk empire. He combined Western and Eastern aesthetics to create his mansion with two wings, with all the rooms built on the same level. On the lower part of one house, he created an entrance foyer with black and white Italian marble flooring in check pattern and a staircase leading to the rooms upstairs.

The largest single structure became the living room with a chandelier from a former palace hanging above. Windows with their ornate frames originally facing outward were ingeniously turned in to be part of the interiors and to act as niches displaying prized objects. Another old house was used for the master bedroom and the dining room.

Thompson’s parties became legendary, with classical dancers, a Thai orchestra and a menagerie of animals like Cocky his cockatoo and other pets that would act as the cast on a theater stage opening to a garden filled with palm trees and the fragrance of frangipani and jasmine. But even for a quiet dinner one could be overwhelmed by just appreciating the beautiful interiors, furniture upholstered in the finest silk and every detail contributing to the overall enchantment of the house — the perfect setting for conversation and for contemplating his exquisite art pieces. The British playwright and novelist Somerset Maugham once told Thompson: “You have not only beautiful things but what is rare is that you have arranged them with faultless taste.”

But not just celebrities were welcome since he would invite students and teachers from the University of Fine Arts to view his collection. After he got lost in Malaysia, never to be found again and with no solid evidence as to the cause of his disappearance to this day, a foundation was created in his name in 1976, with the property and his collection officially registered as a museum. It was no doubt how he would have wanted it: Sharing his passion for silk and art in his architectural masterpiece of a home.