‘Quezon’ and the birth of our broken democracy

From the embers of Heneral Luna and Goyo, TBA Studios’ Quezon rises not as a sequel, but as an autopsy—of power, ambition, and the roots of our political disease. It’s an unflinching look at how the foundations of our democracy were laid not only with ideals, but with cunning compromises and egos as vast as empires.

Under the visionary production of Daphne Chiu-Soon and the masterful direction of Jerrold Tarog, who co-wrote the razor-sharp script with Rody Vera, Quezon is easily the most accomplished entry in the “Bayaniverse.” It’s the most technically assured, brilliantly written, and emotionally intelligent of the trilogy—a film that doesn’t just dramatize history, but dissects it.

The surprise is how entertaining it all is. Tarog transforms what could have been a drab reverent biopic into a political thriller—witty, cynical, and disturbingly current. Here, 1930s Commonwealth-era President Manuel L. Quezon is no saint in sepia, but a shrewd, flawed, and charismatic tactician.

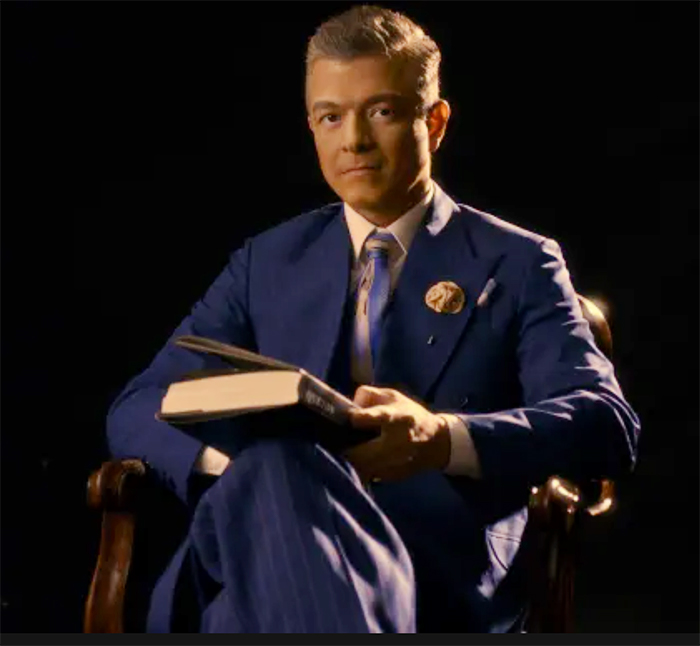

Jericho Rosales delivers a career-defining performance: his Quezon is equal parts charm and calculation, brilliance and moral flexibility. He is the first true “trapo”—traditional politician in the cinematic sense: a man who understands that ideals win applause, but deals win power.

The film’s strength lies in how it dares to humanize heroes. It shows Quezon as both visionary and manipulator, patriot and opportunist—a political pioneer who understood that to rule Filipinos, one must both inspire and seduce them. By exploring Quezon’s Machiavellian maneuvers, the film holds a mirror to our century-old malaise: the entanglement of democracy and deceit, of populism and patronage.

Quezon suggests that the Philippines’ political tragedy did not begin with 1972 martial law or modern dynasties—it began in the 1930s, when Quezon and his peers adapted textbook American democracy into something uniquely our own: a system of elections with lesser and lesser accountability, leadership without genuine humility, and institutions now sadly, constantly hostage to personality and power.

Our imported Anglo-Saxon electoral democracy was meant to empower the people. But in our islands, it mutated into an oligarchy in democratic clothing—a grand illusion of choice where a suffocating number of dynasties rotate like actors in a never-ending telenovela. Elections often became auctions; government, an inherited family business. And a century later, our leaders still follow Quezon’s playbook: eloquent in public, expedient in private, brilliant in speech, but often bankrupt in reform.

Tarog structures the film around Quezon’s rivalries against Osmeña, Aguinaldo, and the shadowy American colonial overseers. Every conversation crackles with energy. Power here is a duel of words and whispers, not swords. Mon Confiado, portraying Aguinaldo for the third time, adds gravitas and tragic weariness to the revolutionary-turned-elder statesman. Romnick Sarmenta, as Osmeña, offers quiet dignity and restraint, the foil to Quezon’s flamboyant ambition. The beautiful Karylle’s portrayal of Aurora Quezon is luminous—she anchors the film with grace and understated strength, the conscience behind the politician’s mask.

The production design is meticulous; the period details are immersive yet not overly nostalgic. Tarog’s direction and Vera’s script merge historical realism with philosophical reflection, using the fictional journalist Joven Hernando as our conscience—a reminder that every republic needs witnesses brave enough to tell uncomfortable truths.

Where the film Heneral Luna roared with patriotic fury and Goyo meditated on youthful duty, Quezon operates on a more sophisticated, unsettling register. It shows that nation-building is not merely a tale of martyrs and soldiers, but of deal-makers and orators—men whose flashes of greatness are inseparable from their moral compromises.

This film forces us to confront a painful question: have we ever truly outgrown Quezon and his brand of politics? Or have we simply perfected his methods with shinier slogans, louder rallies, bigger sordid corrupt deals, and more expensive campaigns? Watching Quezon feels like staring at a mirror with a century’s worth of dust. The faces change, the accents shift, but the political DNA remains the same.

If Quezon was the architect of our political republic, then he was also the father of its enduring flaws—the culture of patronage, the dynastic instincts, the obsession with personality over principle. He sought to build a modern democracy, but what emerged was a feudal democracy—a system run more on family ties, money, and myth.

The well-crafted film Quezon is thus not only history—it is a diagnosis. It reminds us that corruption did not simply appear; it was inherited and brazenly worsened. Our democracy did not collapse—it was compromised from the very start.

As the credits roll, one cannot help but feel both admiration and unease. Admiration for the artistry of Tarog and his cast, unease for how little we’ve learned from the lessons of history. Until we reject Quezon’s seductive brand of politics—eloquent, cunning, and fatally self-serving—we in the Philippines will continue electing not the leaders we need, but the politicians we deserve.