Short, silent (and split up, until together)

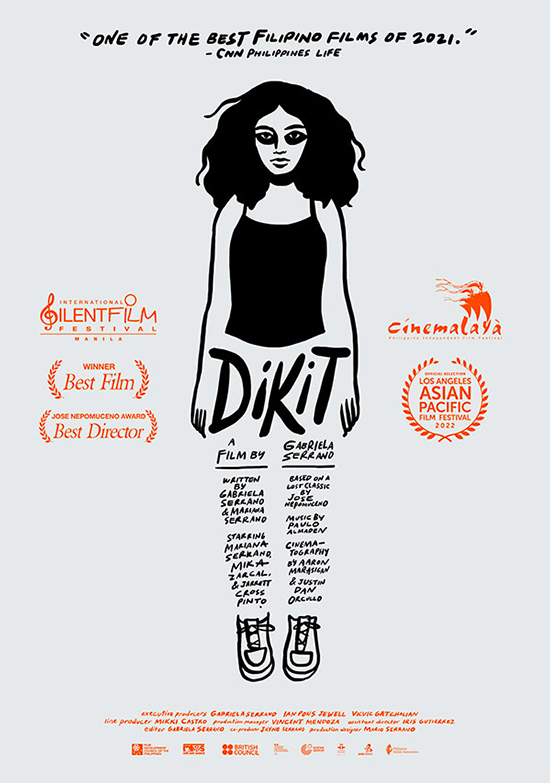

Thanks to virtual niece Mikki Castro, I had the pleasure of engaging in a Zoom interview with young director Gabriela Serrano, whose film Dikit recently won Best Director and the Special Jury Prize in the short film category of the Cinemalaya 2022 film festival — where it was recognized for “pushing the frontiers of feminist cinema and reimagining of Philippine folklore.”

Her directorial debut film also won last year’s Best Film and Best Director awards at the Mit Out Sound International Silent Film Competition, besides being named one of CNN Philippines Life's Best Filipino Films of 2021.

A multi-awarded illustrator and graphic designer for such clients as Young Star, Esquire Philippines, and Ayala Malls for the previous decade, Gabriela Serrano is only 25.

She recounted how a competition for a short film grant led her to submit a proposal for an adaptation of Jose Nepomuceno’s 1927 silent film feature, Ang Manananggal. Although no more print was available, research into Nepomuceno’s work inspired Gaby to conceive of a unique recasting of the mythical horror icon’s prototype.

She set out to meld together a double portrait of two women who wind up fulfilling one another’s needs. And this she does with canny resolve in all of 16-plus minutes, as a silent short film.

A silent film faces a substantial challenge, especially since for nearly a century now, cinematic exposition relies mainly on spoken narrative that is moved along by dialogue. In their stead, a silent film makes do with a chronology of images and purely visual action.

Dikit is a silent film, but it is the loudest I have ever been about my identity, desires and hopes as a woman and as a director.

We’ve gone a long way since Charlie Chaplin’s purely silver-screen era that ended in the late 1920s. I still recall, however, a series of particularly successful films, full features at that, which made do with hardly any spoken words while making us laugh throughout. This was the 1950s-’60s Monsieur Hulot series by the brilliant French auteur Jacque Tati, who as a pantomimist played the central character true to form, as a nearly silent comedian. His six films supposedly used a mixture of languages, but more as sound intrusions. None of the characters said anything important. Eschewing subtitles, he argued that the audience might read them and miss a sight gag. My favorite was Trafic, the last in the series.

Of course, short films would have an easier time without any verbalization. The briefer it is, the more chances it has of allowing imagery alone to present and complete a story.

With Dikit, Gaby Serrano ups the ante by employing the split screen device almost throughout. Viewers would easily acknowledge it as being literally appropriate, even actually called for, since the central character, a manananggal, goes beyond having just a split personality. At night, her wings carry her self-segmented half-body to settle on rooftops, from where she may prey on newborn babies with her elongated tongue, as a viscera sucker.

Gaby posits that her manananggal is a tired old one, herself long suffering from the desire for transformation into a fulfilled woman. The townsfolk who deride her deposit a doll-like figure in half-body in her garden. Discovering this, she is wracked with deep pain.

A young couple becomes her next-door neighbors. The woman is heavy with child, making her a potential victim. But this wife is victimized earlier by domestic abuse, visual evidence of which allows what would have been a horrific predator the opportunity to go against her nature and transform herself into a gender champion.

Split screens show the two women leading initially contrapuntal lives — with the potential antagonist agonizing over her dilemma, while the pregnant woman lies on her own bed, alternately fondling her growing belly and worrying about her spouse’s tendency to pick on her with angry if silent histrionics.

A recurring blood-red frame features the manananggal in her own paroxysms of anguish, contrasting with the adjacent split screen that shows the woman with child sometimes sedated on her own side of the conjugal bed.

Clever and graphically effective are the moments when the adjoining visuals offer parallel patterns of the neighbors’ mundane exercises that involve their respective apartments’ routes of access and egress, the screened doors, and iron-grill windows.

Perceptive reviews written for CNN Life are eminently quotable. John Patrick Manio nails Dikit as the “queering of the manananggal concept,” while Jason Tan Liwag writes: “In the worlds that Serrano creates, female desire, sexuality, and rage are not a source of guilt or shame, but of freedom.” These writers agree on naming Gabriela Serrano as one of “Eight emerging Filipino directors to watch out for.”

Indeed, there is already studied craft in Gaby’s film work. Her Directors’ Notes state: “When the idea to retell the story of a mythological figure presented itself, I felt incredibly drawn to the creature we depict in the film: a girl I felt was hungry for life, but limited by her body, circumstances, and seclusion to exist in the world the way she truly wanted.”

She adds: “Dikit is a silent film, but it is the loudest I have ever been about my identity, desires, and hopes as a woman and as a director. I hope that it quietly but fiercely invites women to find themselves (and each other) through the terrors of life.”

Thus, the manananggal wins out on her determination, with the final frame settling for a single screen that joins the two women together on the same bed of sharing and caring. Dikit na sila, or conjoined, even if their state of togetherness is out of the ordinary.

Apart from the conceptual tweaking and tuning that confidently arrive at this intriguing consummation, the craft certainly shows in the rhythmic cadence of images, split or unified, that adroitly carry the narrative to its desired cinematic end. This admirable pacing may be credited to the director’s additional responsibility as editor. Her co-scenarist Mariana Serrano also shares the acting credits with Mika Zarcal and Jarrett Cross Pinto, while Aaron Marasigan and Justin Orcullo served as directors of photography.

Rounding up the crew were Paulo Almaden as music scorer, Mario Serrano as production designer, Gabriela Serrano, Ian Pons Jewell and Vicvic Gatchalian as executive producers, and Mikki Castro as line producer.

Gaby says that while her team hopes to enter Dikit in foreign competitions and screening festivals, they continue to entertain the option of expanding the film.

Then there are a couple of prospective ideas for future productions, with Gabriela Serrano hoping “to continue telling deeply introspective stories about the feminine identity and youth in the Philippines.” Whether these will also be in silent mode, as short films, there is yet no telling. The undeniable talent made evident in Dikit portends however that there is likely no limit to her and her team’s rising level of contribution to Philippine cinema.

Shown in select partner cinemas nationwide only until August 16, the Cinemalaya 2022 films will have an online run in October via the CCP Vimeo account.