The liberation of H.R. Ocampo

Words failed Hernando R. Ocampo when he needed them most.

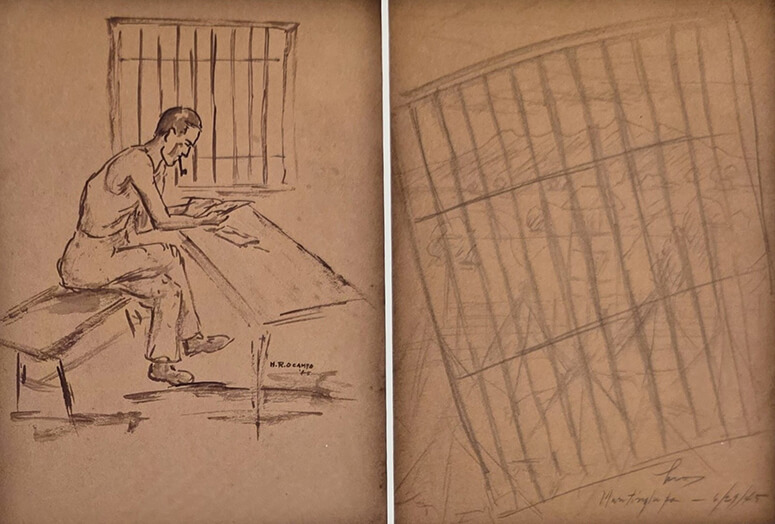

It still unsettles me to think of a man known for color once trusting only words. It is chilling to imagine a future National Artist entering the New Bilibid Prison in 1945 and discovering that the language he loved had abandoned him at the exact moment he needed it. He had been accused of collaboration for working as a scriptwriter and censor under the Japanese. He insisted it was cover for intelligence work with legendary American guerrilla leader Colonel Hugh Straughn, but the Americans were not convinced. Silence filled the cell, as did the imperative to make something out of nothing.

I thought of that stillness at the preview dinner at León Gallery. It was a collaboration with the premium Iberian roasting house Txoko Asador that turned the showroom into a kind of private supper club where the light fell just right on the walls and made every painting look like it might move if you blinked. The turbot arrived soft and bright with capers. The steak from Galicia was perfectly medium rare, a shade of pink that could have claimed my full attention. Yet I kept rising from the table, drifting toward the walls, my Tempranillo moving with me like a shadow.

The paintings took over.

The gallery had become a room suspended between centuries. Juan Luna’s “La Infancia de la Naturaleza” loomed with a dark 19th-century gravity while Jigger Cruz threw the present into the air with a restless insistence that made you feel alive. A nearby display held a rare first edition of Rizal’s Noli Me Tangere paired with its sequel El Filibusterismo, and a tiny poetry book for Leonor Rivera, a whisper of longing beside revolution.

A highlight of the auction is the Nikki Coseteng collection. Its centerpiece is Ocampo’s “Kalaanan” from 1968, a treasure she inherited from her mother Alice Marquez-Lim Coseteng. It glowed with a color so insistent you paused mid-chew.

There was enough in the Coseteng trove to keep the appetite busy, yet I kept circling back to some of the smallest works in the room. These were five panels on wood that refused to bow to the spectacle around them.

These were Ocampo’s Bilibid works, painted in 1945 when the words left him and freedom was a distant thought. Stark. Haunting. Brutal. Intimate. They feel like pages from a private diary that you are not meant to read, the grain of the wood pressing back at you with the memory of a man who refused to vanish.

These five paintings are being offered as a single, unprecedented lot at “The Kingly Treasures Auction 2025” on Dec. 6, opening at P4 million. Every brushstroke carries the weight of scarcity, survival, and stubborn, defiant humanity. “The Plower and Pounding Rice at Twilight” honor labor without pleading for sympathy. “Madonna of the Slums,” and “Forced Labor” capture the grit of a fractured nation. The last, “Grief,” needs no explanation.

History gives us a name for why these works survived, Arnold Margulis, a young Jewish American soldier from St. Louis. He was 18 when he enlisted and found himself in the Philippines, where he somehow crossed paths with Ocampo inside Bilibid. We do not know if he was healing in the infirmary, managing inmates as a military staff member, or merely passing through a prison where a man kept painting to stay human. All we know is he recognized something worth saving. He acquired 18 works on stripped army cots and wooden panels, carried them home to San Diego, and kept them until his death in 2001.

Standing before these five paintings, I felt the shape of Ocampo shift beneath my gaze. I had always known him through the blaze of his later works, the abstractions, the geometry that seemed fully formed, the painterly confidence. I had never paused to imagine the man who lost one language and reached for another. The same fierce intelligence that penned the social protest of Rice and Bullets and the tender promise of his poetry collection Don’t Cry, Don’t Fret was now held captive in color. Knowing he was a writer first peeled back a layer I did not know I was missing and made these works feel even more urgent, almost covetable in the way desire lingers on the edge of propriety.

A few steps away, “Kalaanan” shimmered with the freedom Ocampo eventually won. It is the opposite of the Bilibid works in every way, yet it cannot exist without them. The Margulis collection reminds us that transformation rarely begins in brilliance. It begins in confinement, in fear, in suppression, in the stubborn act of making something human when the world refuses to allow it.

Ocampo walked out of Bilibid a free man. His collaboration was proven to be resistance. The charges dissolved. The painter stepped forward. The writer remained behind, locked in that cell, unfinished, leaving the brush to take the place of words.

More than mere objects for sale, these five panels are proof of survival. They are the evidence of a life that had to be remade. They are the reason Arnold Margulis carried them across oceans and decades.

And now, for one lot, opening at P4 million, they return home, waiting for a collector to see not only the paint, but the man behind it, the isolation he endured, and the voice he forged when the world refused to listen.

* * *

The Kingly Treasures Auction will be held on Saturday, Dec. 6, at 2 p.m., at León Gallery, Eurovilla 1, Rufino corner Legazpi Streets, Legazpi Village, Makati City. Preview runs daily (9 a.m. to 7 p.m.) until Dec. 5.

For inquiries and catalog browsing, visit www.leon-gallery.com or contact info@leon-gallery.com or +632 8856-2781.