Bridging two cultures: How these Gen Z Chinoys are carrying tradition forward

Growing up, Chinoys experience two worlds within the confines of their homes. At breakfast, some eat dimsum, but come dinnertime, it's a plate of adobo at the table. They offer incense to their Chinese ancestors, and have taught themselves to say "po" and "opo" to their Filipino elders. During Lunar New Year celebrations, the whole family gathers together, just like how Filipino families share media noche on New Year's Eve.

Being constantly exposed to two distinctive cultures, doesn't it get confusing, though?

PhilSTAR L!fe spoke to three Gen Z Chinoys to learn how they see themselves in the midst of this cultural synthesis, and how they're keeping their heritage alive in these modern times.

The blended Chinoy experience

For Clark Angelo Siao, 23, growing up in a Chinese-Filipino household in Binondo was a lesson in intercultural cooperation.

A fourth-generation immigrant, whose Chinese grandfather fought with Filipino troops in World War II, Siao and his six siblings were raised by a full-Chinese dad and a half-Chinese and half-Filipino mom. It is normal for him and his siblings to visit a Buddhist temple to pray then go home and enjoy Bicol express or sinigang.

"I think if I'm asked [whether I'm more Chinese or Filipino], I usually tell them that I'm Chinese but I do have Filipino blood because I do also have a Filipino passport. So I do recognize that I'm also a Filipino," Siao told PhilSTAR L!fe.

Raised with an iron fist—he once got a 30-minute scolding for forgetting to greet his uncle when he got home from school—Siao admitted he initially resented the strict upbringing. Today, though, thriving in De La Salle University, Siao can "see the fruits of my parents' discipline."

Although he went to Chinese schools until high school, where Filipino students were a minority, he deeply understands Filipino culture, too—a fact that many Pinoys don't get about Chinoys. Siao, who is editor-in-chief of The La Sallian, uses Filipinos' misconceptions about Chinese-Filipinos to have fun sometimes.

"Some people assume that Chinoys keep to themselves or don't eat Filipino food. I remember I was already in college [when] I joked to my blockmates that I hadn't tried Jollibee and they believed me," Siao told L!fe.

"I think they don't understand that the Chinoy experience is often blended and not isolated from the rest of the Filipino community," he added.

It would be a shame if Chinoys did keep to themselves, especially during Lunar New Year celebrations. According to Siao, the Spring Festival in Binondo attracts mostly Filipino TikTokers eager to go on a food trip in the world's oldest Chinatown.

Rather than stand shoulder-to-shoulder with revelers in Ongpin St., Siao and his family go with their traditions. They visit the temple and receive ang paos—"It's sometimes the reason why we go to the temple, because people hand out ang pao in the temple," said Siao. He and his family also stay home to share a big meal and eat tikoy, since they receive numerous boxes of the delicacy this season.

"But not all of us like tikoy," admitted Siao.

A marriage of traditions and superstitions

Growing up with a mainlander father and Chinoy mother, Jennylyn Wu, 22, could draw a clear line between the two sets of traditions and superstitions her parents subscribed to and raised their two kids on.

Their house in Binondo has numerous statues of Buddha, to whom incense is regularly offered. Instead of the usual ringing alarm clock, Wu and her sibling are awoken every morning by a CD player of Chinese songs; then it's dim sum for breakfast with their dad as their mom leaves for work.

For dinner, it's Mom's turn. It's sinigang, maybe adobo, for dinner. On Sundays, she goes to mass at Binondo church. She also forbids her daughters to sit on the floor or cut their nails at night "because your family members are gonna die," Wu told L!fe, recalling her mother's ironclad rule.

Despite being exposed to both Chinese and Filipino practices and myths from a young age, Wu had a tough time connecting with the Pinoy kids who would play on the street fronting her family's business.

"Kasi nga singkit, tapos maputi, tapos chubby; I was bullied throughout my childhood," said Wu, who, like Siao, went to Chinese schools growing up.

To try to become "more Filipino," she practiced speaking Filipino, and a bit of Bisaya, with her Pinoy nanny. Wu also hung out with her yaya while the latter was watching It's Showtime, where Wu learned to enjoy Pinoy humor, courtesy of Vice Ganda and Vhong Navarro.

"Just so... when I [went] outside, I'd know how to communicate...[The Pinoy kids might] think that, 'Oh, you're not very Chinese. You're just like us'," Wu told L!fe.

Her acclimation strategies expanded when she became an adult. As a professional chef, she is now surrounded by a healthy mix of Chinoys (her bosses) and Filipinos. Wu joins them in drinking games, joins in on jokes, and attends Simbang Gabi even if she doesn't celebrate Christmas ("just to feel the Filipino Christmasy vibe").

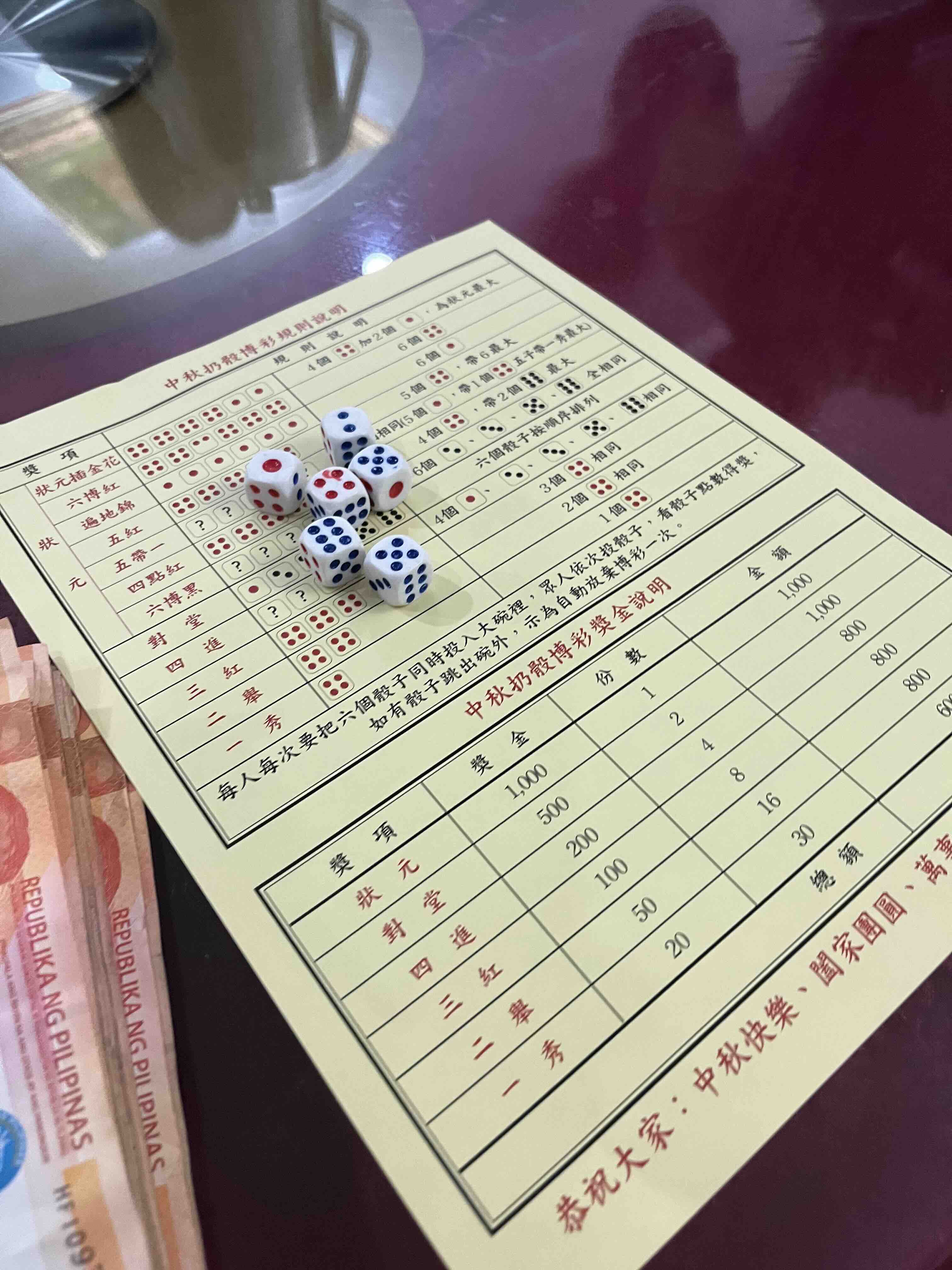

Still, Wu stays true to her Chinese heritage, especially during Chinese New Year, which, for her family, is a one-to-two-week celebration involving lots of cooking, eating, having only round fruits on the table, offering incense, receiving ang pao, and playing dice games.

"I think now I do feel that I'm not full Chinese, I'm not full Filipino. I'm already Filipino-Chinese in the heart," Wu said.

The best of both worlds

Born and raised in Cebu, Shaila Sy, 26, has a mother who is full Chinese, born in Iloilo, and a father who is a mix of Chinese, Filipino, and Spanish, born in Cebu. Their household, bursting with four daughters, was rich in Chinese traditions.

"We were introduced to Chinese food very early on. We were also taught to call each other by the respective Chinese names," Sy told L!fe. As the second oldest sister, Sy calls the eldest "achi"; the two youngest call Sy "ditse"; and everyone calls the youngest "siobe."

"We were also very encouraged to be hardworking and frugal with money. I think that is a very typical Chinese trait, being simple and humble, even if you can afford luxury," Sy said.

Respect for all elders and honoring deceased ancestors were also ingrained in the Sy sisters.

Because they went to a Fiipino-Chinese school, which celebrated both cultures equally, Sy never felt out-of-place with her pure Filipino friends. At school, they observed Buwan ng Wika every August, and celebrated Chinese New Year every February. The students had both English and Mandarin classes.

"I grew up with a lot of people who were just like me... I was very thankful that a lot of my classmates, batchmates, had a similar upbringing," Sy told L!fe.

At home, she and her family spoke mostly in English, sometimes in Bisaya, while her parents talked to each other in Hokkien, the common language among the Filipino-Chinese community, said Sy.

Although she is now based in Manila, working in fintech, Sy has brought along her childhood Chinese traditions, particularly the ones during special occasions. For birth or death anniversaries, for example, they would burn incense sticks, offer food at the home altars dedicated to deceased ancestors, and make sure to wear black or white. For gifts, there is the ubiquitous ang pao, even for the adults.

Lunar New Year celebrations, as expected, involve a lot of food.

"At home, we would always cook tikoy, and my parents would give it out to their friends and clients. We'd also have big family gatherings," said Sy, who continues these traditions by traveling home in time for Lunar New Year.

For Gen Z Chinoys, identity is not about choosing one culture over the other, but embracing both. By blending traditions, languages, and heritage, they are redefining what it means to belong to a layered, complicated Filipino society.