REVIEW: ‘Anino sa Likod ng Buwan’ expertly teases out recurring function of violence in the countryside

Award-winning Filipino director Jun Robles Lana's Anino sa Likod ng Buwan is being revived by IdeaFirst Live!, the theater arm of the production outfit founded by Lana alongside producer Perci Intalan. Lana penned the one-act play psychodrama for Bulwagang Gantimpala’s 1993 playwriting competition, where it copped the top prize. In the same year, Bulwagang Gantimpala and Artistang Artlets of the University of Santo Tomas adapted the material on stage.

By 2015, Lana would pump new life into the text by turning it into a one-take, two-hour motion picture, whose visuals are deeply monochromatic, grainy, and tensely confined by its 4:3 aspect ratio and whose narrative is propelled by the terrific trio of LJ Reyes (in a turn that won her an Urian), Adrian Alandy, and Anthony Falcon. It might as well be Lana’s best and most decimating work to date.

The latest stage iteration, set to run at the PETA Theater Center from March 1 to 23, summons the spirit of the previous adaptations in that it maintains the material’s enduring commentary even as it abandons the visual paraphernalia contributing to the appeal of the screen version due of course to differences in form.

This time, motoring the vision are theater mainstays Elora Españo and Ross Pesigan—who both worked on Pumpon ng mga Gunita, a devised play on Jose Rizal directed by Josefina Estrella and performed in Germany last year—alongside Martin del Rosario, in his stage acting debut.

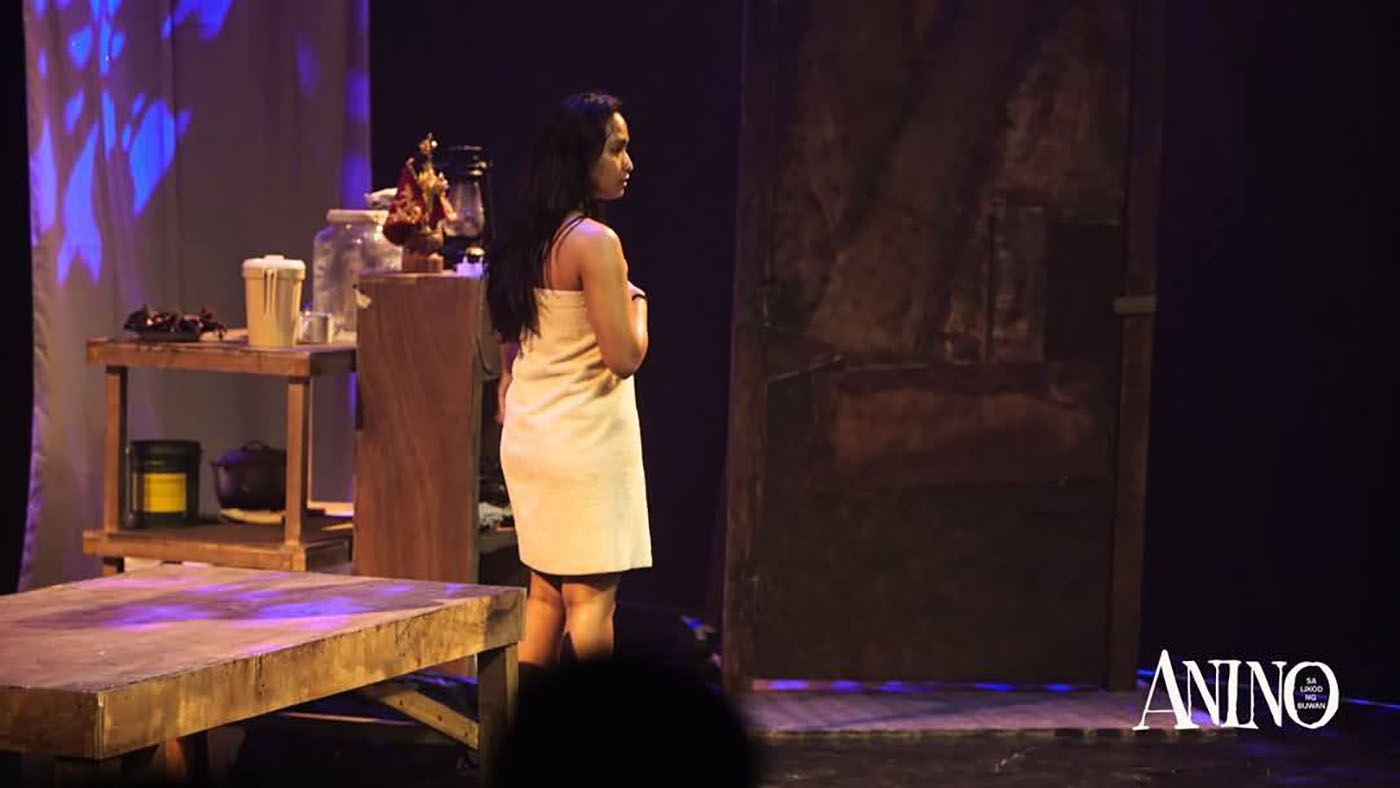

The story tracks the anxious relationship between two refugees and a soldier against the backdrop of the armed struggle between the state military and the communist resistance around Marag Valley, a northern Philippine hinterland, in the early 1990s. The bare-bones set—wooden bed, chairs, and tables; a Santo Niño figurine atop a makeshift altar; and foliage projected on large strips of white fabric—parallels the show’s deconstruction of what constitutes the violence that’s still rustling in the countryside.

Around a shack where the characters await a telling lunar eclipse, hence the title, the female protagonist, Emma (Españo), quietly bathes herself, consuming the water supposedly stored for cooking dinner, then later joins the conversation between her partner Nardo (Pesigan) and the visiting Joel (del Rosario), a sexually tempting soldier who has helped the couple settle into the village a year ago and occasionally secrets food and medicine for them.

Like the card games and heedless chatter they entertain themselves with, the characters thread a dangerous line—some sort of political ménage à trois that soon buckles under its own weight—stealing glances and acting magnanimous in one moment, then exposing us to their primal desires in the next.

Lana and director Tuxqs Rutaquio sexily ratchet up tension through dialogue (often migrating between conversational and literary) as well as the carefully measured blocking, showing us the casual display of bravado among the two male characters and the sexual poison that might alter the course of the revolutionary cause at its center. “Pinupukaw mo ang hayop na nakatago sa kaibuturan ko,” says Emma at one point.

A rather long juncture of deceptive decadence between Emma and Joel does provide layers to the material. The show is at its peak when they refuse to drop the act, sustaining this inquiry into the phenomenon of desire as no longer a function of the self but perhaps a function of a larger cause, whether revolutionary or otherwise, and how violence bleeds into it just as these lives cannot move past the constant reminder of gunfire in their environment or fresh news of soldiers being killed in the forest.

Though the artistic recalibrations from the screen to the stage don’t exactly create a spectacle given the nature of the material, what really propels the staging forward are the performances to which it affixes its articulations.

For a theater first-timer, del Rosario neatly snuffs out any doubts the viewer might have had about his portrayal; he revels in his character’s cunning ways as though it’s second skin; his sex appeal, almost feral. He remains an irresistible presence even as his Joel turns too nasty, too cruel to watch. On the opposite end, Pesigan likes to retreat to a seemingly tentative performance, which perhaps suits a character who at times tries to act dense and impulsive—playing as someone who simply knows the rules of the game.

In many ways, though, it is Españo that shrewdly engines the staging. She exudes such a complex response to Emma’s grief as her father, a rebel leader, suffers in the enemy’s hands, drawing out all fiber of emotion from every line, every movement, every horny, shameless attempt at cornering the one that holds her captive. It is through her that the violent calm of Lana’s vision combusts.

In its most granular, Anino sa Likod ng Buwan functions as an unflinching gaze into a nation that’s so often willing to eclipse its past, sans any real sense of reckoning. Its design is minimal, but the result is nothing short of immense.