Heritage, memory, and modernist art: At home with Jose Mari Treñas

The ship of history can run shallow or run deep, follow not just maps outlined by ancient documents but also sail down the rivers of recollection, docking here and there in the places of distant memory.

For Jose Mari Treñas, the act of collecting is just as slow and deliberate. It’s a meandering journey to connect to fragments of the past, a languid tale that both discovers and retraces roots of identity and family.

It combines the thrill of the chase, as well as a steady accumulation. In his universe, there are legacy objects that have been handed down in the tight Ilonggo community but also finds pursued across the country (and other collections).

There are fabulous pieces from the famous stewards of Philippine culture but also precious objects trawled from other families’ personal histories. Thus, there are reliquaries and church pews—but also magnificent porcelains encircled with dragons from the Arturo de Santos collection or silver treasures from Ramon Villegas, both legendary stewards of Filipino culture.

A pair of slender, fluted columns from an ancient “visita” in Oton stands in one corner of Joe Mari’s home. Oton was one of the major ship-building centers in the country—pre-dating the Cavite shipyards in Luzon. “Visitas” are smaller Catholic missions intended “to extend the Church’s reach to native populations at a more modest cost” without the pomp of a proper church and convent and with fewer friars. Nevertheless, the stately elegance of the pale columns with Corinthian capitals hint at more prosperous origins.

Oton was a bustling Malay settlement in Iloilo even before the arrival of the Spanish. (The gold death mask named after its town of origin is the highlight of an important permanent exhibition at the National Museum in Iloilo. Joe Mari’s mother, on her own personal journey, would wear carnelian necklaces excavated in Oton.) This place, after all, would be not just where the first galleons would be built, but also the primeval balanghays, sitting as it does astride a strategic strait in Panay.

The Treñas family is one of the most well-known in Iloilo, but not many people know that Joe Mari is also a Barcelo from Bugayong in Antique, which at one point was the capital of the province in the 18th century. His ancestor Simon was an enterprising young man who was a self-taught entrepreneur, first schooled at the Ateneo Municipal, but who would become—according to colonial records—the biggest landowner of Antique by age 20. The Queen of Spain, possibly in recognition of his fealty (and numerous tributes), would send him an exquisite ivory Sto Niño, that would be dressed in a suit of silver embossed armor. Barcelo would, in turn, donate it to the parish church—but alas, it would disappear sometime in the 2000s never to be found again.

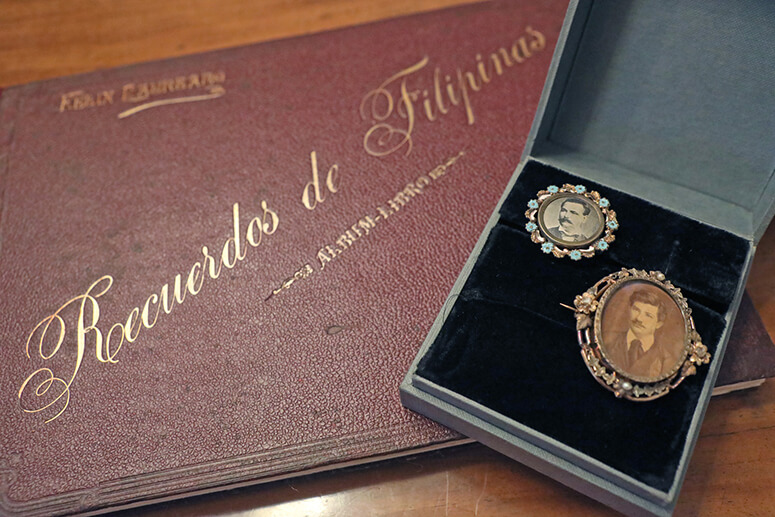

One of Joe Mari’s most prized possessions, therefore, is a pair of miniature portraits framed in rough-cut jewels. One of them is of Don Simon; the other of Don Jose Maria Perez of Barotac Nuevo, both of them his great-grandfathers on either side. (His mother, Soledad [Nena] Perez Treñas would inherit not just the fine aristocratic looks of the Barcelos and Perezes but also their love of art and music.)

Treñas describes himself, first of all, as a scholar whose interest in the finer things in life was sparked as a young college student at the Ateneo de Manila. Its art gallery was the staging area of the fabulous Fernando Zobel collection of Philippine modern art. He remembers sitting in front of the magnificent abstract work titled “Church Silver” by Jose Joya, as he caught up on his homework. (It would later inform his selection of another slate-gray magnificence by Joya called “Rites.”)

Serendipitously, he would also find inspiration at another university museum, the Fogg at Harvard, where an astounding Philippine ivory crucifix would pique his interest in Filipino religious art.

He would have the good fortune to meet and interrogate the mid-century moderns still alive, Hernando R. Ocampo and Victorio Edades, but also Manansala, Malang, and Dalena, and began collecting them and their contemporaries. Thanks to these connections—Joe Mari was able to steadily put together a growing collection of precious paintings including a seminal “Mask” by H.R., a Nena Saguil surreal masterwork titled “Bride,” and a Fernando Zóbel it took him decades to find and acquire. Most of his hoard has been frequently featured in Philippine and international museum exhibitions.

His collecting accelerated as a Filipino ex-pat living in Manila working for a multinational and he was thus able to feed his increasingly well-developed tastes.

Eventually, he would find himself in the circle of influential collectors that would include Ramon Villegas, one of the most pre-eminent scholars of Filipino culture.

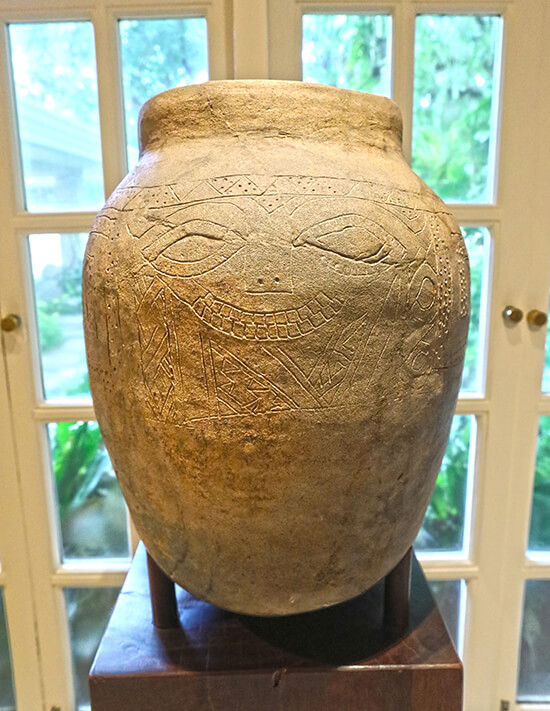

His interests would grow exponentially to include porcelain, tribal art and the maitum. (Joe Mari owns the first anthropomorphic piece to be discovered in Southeast Asia.) He also collects pre-colonial gold as well as Spanish-era furniture and ivory.

Joe Mari’s fascination for pre-colonial gold would begin with a chance visit to a semi-permanent exhibition at the Cultural Center of the Philippines—he would visit its galleries during intermissions at classical concerts. Here, he would behold the spectacular holdings of hacendero Arturo de Santos, renowned collector and aesthete.

The day we visit his collection, a spectacular ivory piece of a Cristo Expirante (Christ about to draw his last breath) has just arrived. It is covered with a gold loincloth from the 18th century decorated with tassels of mine-cut diamonds. The masterpiece is arranged in front of an exquisite Justiniano Asuncion of the Virgin of the Holy Rosary and an assortment of precious Philippine silver.

His furniture collection does double-duty as working pieces: A tall Ah Tay cabinet, covered with fine carvings of peonies overflowing from a Chinese vase, discreetly contains layers of jewelry; a refectory table with boar’s-head feet sits in his dining area; an Augustinian double-headed eagle cabinet, decorated with pineapple finials, stores his books. There is a baul mundo that used to travel the world on the Manila galleon as a footboard to his bed.

For Joe Mari, the art of collection is not mere acquisitiveness but a kind of gentlemanly pursuit, much like breeding race horses or studying rare botanical specimens, with as much as science and precision as these pursuits entail. (Even his garden, designed by Shirley Sanders, is a stunning tableau of fern trees and orchids dotted with Soong and Tang vases, and Ming martabana jars.)

More importantly, Joe Mari consciously seeks objects that speak to his heritage—and the greater Filipino cultural space. It’s not an easy task, requiring mindful curation and as Ramon Villegas once described Joe Mari’s habits, “brutal editing.”

“I can’t stand clutter,” he declares. The walls of his home are painted a plain white and there are no carpets to distract the eye. For his tribal art collection, he commissioned the premier proponent of minimalist architecture, Ed Calma, to design the room to contain it. It’s the perfect setting, geometric and spare, with a Manuel Ocampo painting of a skull sitting on the floor in a kamagong frame. An Abueva bench is in the center of the room to encourage contemplation.

“There is resistance to combining the old and the new these days,” says Joe Mari wryly, “but I believe that we can do that if the objects and the art are of the same and equal quality.”

The key lies no doubt in the continuous distillation—almost relentless parsing—of his collection. It’s a nightly ritual, says Joe Mari, as he circles his house like a sleepless hawk each evening, traveling through time and space, family and history in the tireless pursuit of perfection.