Safeguarding sex on stage and screen

Sex or nudity onstage or onscreen has always been tricky. Years ago, when I acted in a local production of David Hare’s play The Blue Room—a play popularized by Nicole Kidman’s baring all on a Broadway stage—I became familiar with that reality.

I was in my 20s at the time so I didn’t think going nude was a big deal. I was in a leap-before-you-look mode—willing to do anything for my craft. For me, there was also no question that nudity had an integral place in art. Anyone who has stared at a Botticelli knows that. I was also the kind of kid who had watched Volker Schlöndorff’s The Tin Drum by age 11. When the offer came to be in a piece that required that kind of risk, I grabbed hold of that chance to grow from the experience; and I did, in many ways, back then.

Emilia Clarke confessed she would “cry about (intimate scenes) in the bathroom” after shooting them. A producer yelled at Jason Momoa to take off his intimacy pouch “for your art!”

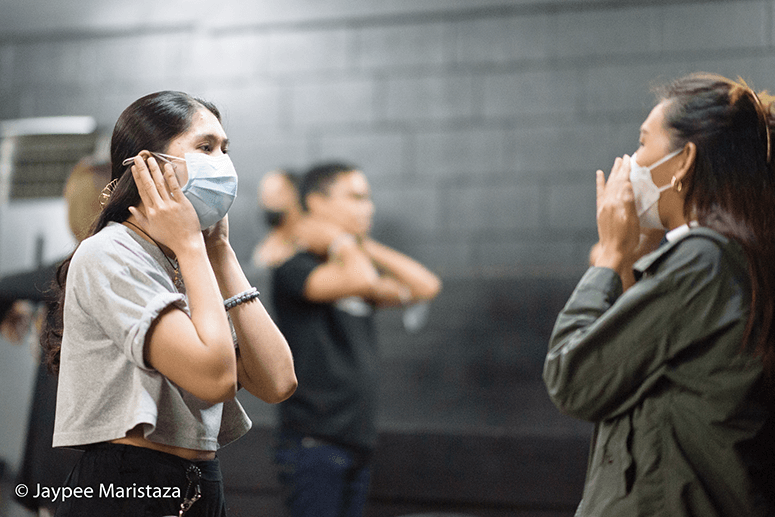

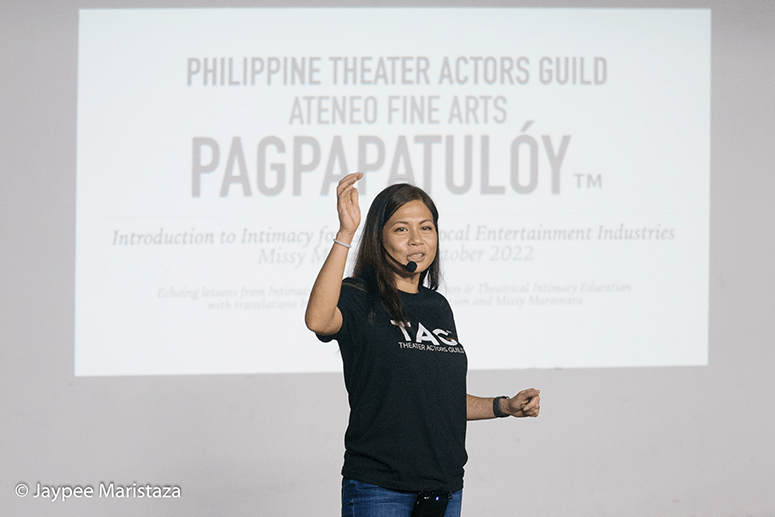

Fast forward 20 years: I find myself in an Intimacy Seminar and Workshop at the Philippine Theater Actors Guild (TAG PH). It’s being conducted by actress, educator (and now intimacy coordinator) Missy Maramara. Before the session, all I knew about “intimacy coordinators” was from a recent Deadline article about House of the Dragons. Apparently, even in a big-budget HBO show, the role is quite new. But more and more, the industry is finding it necessary to have one to safeguard both actors and the production.

Intimacy Coordination (IC) for television and film, or Intimacy Direction (ID) for theater, is an initiative to establish a culture of consent in the performing arts. Dragon’s precursor, Game of Thrones, did not have IC; it is no surprise that cast members have since come out about how intimate scenes were mishandled on set. Emilia Clarke confessed she would “cry about (intimate scenes) in the bathroom” after shooting them. A producer yelled at Jason Momoa to take off his intimacy pouch (the protective covering for his genitals) “for your art!”

These kinds of incidents are not alien to us here in the Philippines. As TAG PH officers, Missy and I have heard, firsthand, the horror stories: unchoreographed sex scenes, actors left to their own devices or told “alam niyo na ‘yan,” uncontrolled number of people on set seeing an actor’s genitalia, actors being unable to get out of a risqué scene that wasn’t fully explained to them, productions that blur the line between fiction and reality.

I recall the first time during The Blue Room rehearsals when I had to doff my clothing. I was proud to have been able to steel myself on my own. Did I need ID back then? According to Missy, definitely. Not that things were mishandled, not at all, but with an intimacy director, I wouldn’t have had to go through my body shame issues alone. Or I could have processed performing in the buff with my dad and ninong sitting in the third row of the theater! At the time, proving my mettle became my focus, going nude my “gimmick.” Thus, there were missed opportunities in my performance. An intimacy director could have set a standard to safeguard the artist in me that just wanted to tell a story properly.

Ultimately, that’s the result of intimacy work—to encourage more creative options in storytelling. Missy says IC and ID decrease “the precarity of performance spaces by equalizing the power dynamics within artistic collaborations.”

Intimacy coordination practice transforms that mindset. It is an agreement between the actor and the powers-that-be that the actor is allowed to be in a position of choice — about where to be touched, who’s to touch them, how and when they will be touched.

Her focus on power dynamics is particularly relevant since we, as a country, are so mired in it. Intimate scenes are made even more complex by the hierarchy of the industry, whether on or off the set. As a Filipino actor, you’re likely to feel more beholden to the producer who writes your paycheck than to yourself. Intimacy coordination practice transforms that mindset. It is an agreement between the actor and the powers-that-be that the actor is allowed to be in a position of choice—about where to be touched, who’s to touch them, how and when they will be touched. Intimacy coordination practice sets a standard language that everyone in the production uses to ensure no one’s boundaries are violated. It also makes the actor an active collaborator in creating the scene way before it is staged or shot. Thus, according to SAG-AFTRA, the American entertainment labor union, having an IC or and ID can even “reduce financial, insurance or market-related risks, as well as avoid unnecessary production delays.”

The practice of IC and ID is a de-sexualized process rooted in continuous, retractable consent. For actors of Generation X or older, retractable consent is definitely something we’re not used to. We grew up with a grin-and-bear-it attitude, not just in portraying sex or nudity, but also issues like incest, abuse, suicide and other kinds of trauma. For a young actor like me in the early aughts, I always had something to prove and never wanted to rock the boat. Throw something at me, and I would “just deal.” Some actors cling to that kind of grit because it might make for a better artist, but we’re seeing that IC and ID open up the creative space for even braver choices, precisely because everyone is assured that their boundaries will be respected at all times.

While Missy is on her way to certification at Intimacy Directors and Coordinators and taking additional training with Theatrical Intimacy Education in New York, she is also working with fellow Ateneo teachers Ron Capinding and Ariel Diccion to adapt the concepts and translate them into Filipino language to create a system that is more culturally appropriate. They have named it Pagpapatulóy, after the Filipino word for “intimacy.”

TAG PH now wants to amplify Pagpapatulóy’s place in the local performing arts scene. Missy launched the new direction with a workshop last Oct. 3, 2022, attended by members and guests, as well as Atenean and non-Atenean students alike. We will continue this work even as we recruit new members in December, and even as new officers take our places. We see Pagpapatulóy as a step in the right direction for the entire industry. It’s not just about being woke. It’s about giving—and getting—the respect we all deserve.