Looking inside Agnes Locsin

At the outset, watching her choreography in the Neo-Ethnic dance genre she conceived, a conservative mind with set ways and considerations could dismiss the choreography as utter disrespect of tradition—perhaps because the mind is ill-informed about the meticulous process Agnes Locsin goes through in transforming a tradition into a modern dance genre based on movements and intricacies that, in fact, respect tradition.

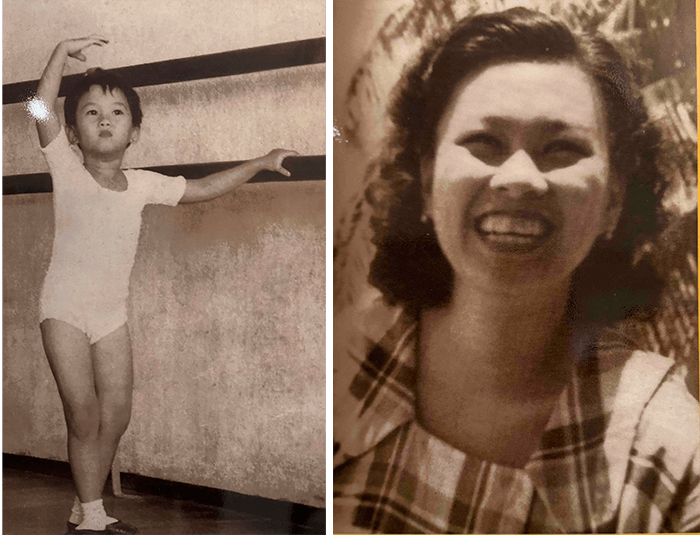

“Dance Is My Life”—an exhibit of Agnes’ creative journey in dance, meticulously documented and curated by Pamela and Virgilio Castrillo at the Davao Museum of History and Ethnography until March 31—considers Agnes’ massive contribution to modern dance, and is an important addition to the museum’s list of exhibits. The walls are papered with photographs of Agnes from the time she was her mother’s ballet student as a child, plus Agnes’ own tributes to her mother, Carmen D. Locsin, a ballet teacher who started what is now the oldest dance studio in the country (at 80 years old this year). Agnes aptly pays tribute to her mother with her blown-up photograph and a mention that “ Mommy Nitang”s dedication to teaching dance at their home preceded Agnes’ birth by a good 10 years.

Exploring the exhibit, Agnes’s mindset and intent become clearer: just how dedicated she is to Filipinizing her body of work, which was triggered by her mother emphasizing the inclusion of a Filipino piece or two in all Agnes’ presentations. In this, Agnes not only complies with her mother’s wishes, but goes beyond that, staging complete show repertoires made up of Filipino-themed dances. Her process, which she outlines in detail in her book, Philippine Neo-Ethnic Choreography: A Creative Process, started when, as a student at Ohio State University, she introduced Igorot and Muslim steps and moves for her Movement Exploration class, astoundeding both her classmates and professors.

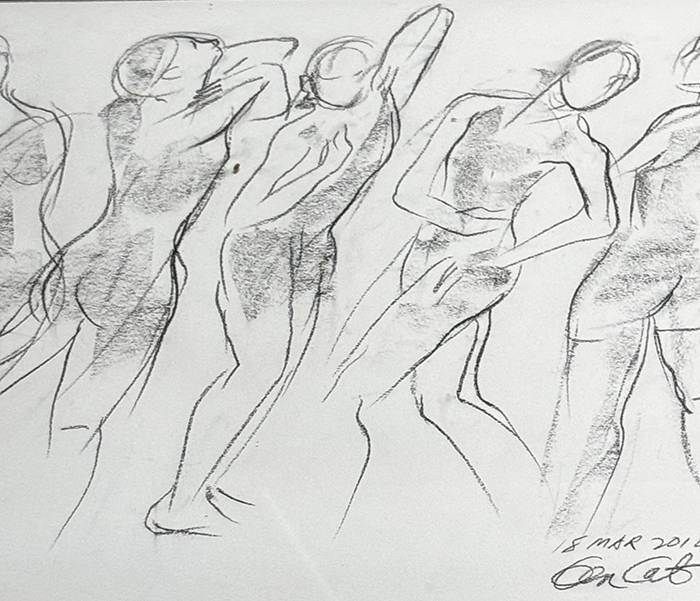

Photos and drawings of Agnes’s dancers by National Artist Ben Cabrera and the late Santi Bose, one of CCP’s early Thirteen Artists and founder of the Baguio Arts Guild (and a pioneer in the use of indigenous materials), help document some of the inspirations and output of her work, underscoring the richness of Filipino dance culture.

Also highlighted are her collaborative works with other artists like Joey Ayala and librettist, Al Santos, whose first team-up, Sa Bundok ng Apo, is represented by a photograph of the first cast.

Agnes is undoubtedly a storyteller, making full-length dances out of local history and rituals rife with rich research as in her big dance hit, Encantada, set in the Spanish colonial era where non-conversions to Christianity produced a divide between local rituals and Christian practices. In short pieces like Moriones, which focuses on a group of Roman centurions in search of their fellow centurion who pierced the side of Christ on the cross and was said to have become a follower of the risen Christ, “Locsin-ish” movements, i.e., athletic dancing and sharp, angled movements, succeed in telling the story (The original mask worn by principal dancer, Alden Lugnasin, is on exhibit). But even in pieces that put across simple concepts, the message comes through, as it does in Taong Talangka, conveying “greed and envy that reaps the fruit of destruction.” Going through her past repertoire at the exhibit, one realizes how much more of her work is left to witness.

In her “happy place” in Davao, Agnes is unquestionably attached to her surroundings and dedicated to her chosen art of dance. She has built at least three dance studios where she holds classes, all airy and spacious. Her performance places can accommodate a sizable audience for her annual recitals and inevitably feature the signature wood of her choice, bamboo, harvested from her family’s farm, a tree-laden landscape where she can practically name each of the tree species, and because she asks each guest to plant a tree, she recalls each tree and its planter.

And since she is an advocate of environment preservation, trees occupy a special shade in her heart, as she identifies herself as a “tree hugger.” Works like Puno, Ugat, and a work described as an ode to leaves are among those that justify her tree-hugger title.

As she prepares for the upcoming recital, her own house is presently a costume workshop with roll upon roll of fabric in an assortment of colors and weaves. On one table is spread several child-sized lace tops with floral appliques which she herself has sewn on. Every nook and cranny is filled with items and objects, organized properly, ready for costume production. More sketches by National Artist Ben Cabrera and artist friend, the late Santi Bose are displayed on the wall. But perhaps the most impressive are the charcoal sketches of Agnes herself which are portraits of the dancers she loves. One portrait of a female dancer has her on a background of large and small florals which are found in the Locsin farm. Another is of a male dancer lifting a female dancer. From afar, the line drawings at the back of the male dancer look like wings, but on closer viewing, they are falling human figures emerging from the dancer’s back.

The deep attachment she has nurtured with her dancers whom she has closely mentored and is still mentoring go beyond the dance spaces where she literally molds them like clay. More recently, she has started developing what she calls “ ethnic tap,” a hybrid genre of tap dancing and ethnic body, arm and finger placements danced to ethnic tribal music which she has taught to a few of her dancers. Presently, the closeness she has with four of her lead dancers have made them a part of her persona: Biag Gaongen and Alden Lugnasin, both former lead dancers she refers to as her third leg and her third eye, respectively; and two young female dancers, Sam Martin as her left hand and Nikki Uy as her right hand.

Not only is Agnes Locsin setting up her legacy of dance for which she has been cited as National Artist; rather it goes deeper than that, for beneath the strict, demanding, exacting dance diva she is reputed to be lies a congenial storyteller, a soft-hearted giving individual whose reach goes well beyond her art.