Your life in calendars

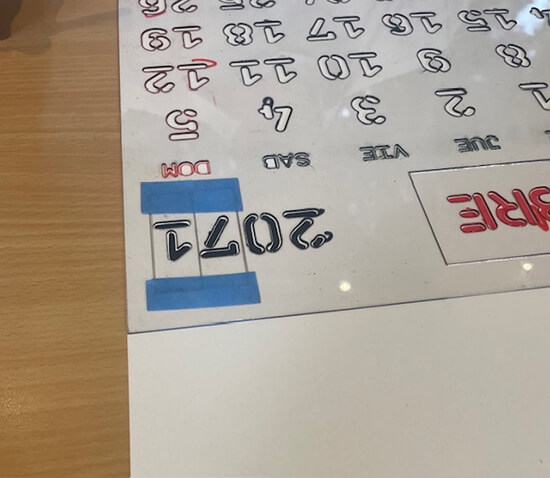

If you casually strolled past the Greenbelt Gardens this past week, you may have noticed a slightly unusual sight: a young Spanish man seated at a desk, earnestly stenciling the letters and numbers of a calendar. If you had looked a little more closely, you may have been surprised to see that the calendar he is working on is for the year 2071!

The artist is Ampparito, well known back in Spain for thought-provoking, humorous, and entertaining projects that are a cross between installation and performance. It is art outside the box, where everyday objects and experiences take on new meaning, unfold in all directions, and shake you out of your complacency for the ordinary. Never again will you take the mundane for granted.

Take, for example, Ampparito’s orange tree on a sidewalk. If you were to plant such a tree in a public space, what is to stop people from picking all the oranges? The artist then constructed a metal cage for the tree, measuring plenty of hands and oranges so that if a child were to put their hand through the bars and grasp an orange, he or she would not be able to pull it out!

In another instance, Ampparito and his team repainted the rusty gate of a factory that had been closed for 33 years. Back then, a thousand workers would pass through those gates every day. Ampparito was able to track down nine of these people and asked them to recall the original shade of green of the gate. Since almost all chose different shades, the team mixed all the shades together and repainted the gate with the result. It was about working with different memories, blending them into new shades of green, to come out with something similar to the truth.

Another thought-provoking project was his take on the practice of putting signs on cars saying “no hay nada de valor” (there is nothing of value). Beyond installing alarms and other deterrents to theft, this makes an appeal to the would-be thief not to waste his time, and also to spare the car owner from having to replace the glass. Ampparito made giant versions of the sign, putting them on street walls, billboards, and even horses in fields. Some locations almost got them into trouble, as you may imagine (“Why are you putting that outside my house?? I’m going to call the police! I’m going to come back with three people and beat you up!”). The artist then ponders that perhaps there really was something of value in that house.

We should not be surprised, then, that the performance of stenciling calendars up to the year 2099 while seated outside the Ayala Museum would lead to something similarly provocative at Art Fair Philippines. When the fair opens privately on Feb. 5 and then to the public on Feb. 6, you may expect that Ampparito’s 75 years’ worth of calendars will be hard to miss. The artist is playing around with many ideas of how they can be displayed—in lines? Wrapped around the stairs? Covering an entire wall or just in groups at eye level, so the dates and years can be clearly seen?

What started this “Esperanza de Vida (Life Expectancy)” project, a combination of performance (drawing all the calendars of one’s life within a week) and installation, was the recent death of an uncle, which forced the artist to start thinking of life and mortality. But this is not necessarily a macabre exercise. There are many ways to look at being in a space where one of the calendars (inevitably) contains the day of your death. You could view it as all the years pertaining to life, and what you would do with those days. Where will we travel this year? Perhaps by this decade, your children will be married? What will technology bring 20 years from now? All the questions of your life.