Blood, sugar, breath and cosmos magik

Rock history is awash in tales of wild music producers, adding to the manic energy of studio sessions. Accounts have it that Phil Spector would show up at Ramones or Leonard Cohen recording sessions, gun in hand, waving it around like a menacing baton. Brian Wilson would instruct a whole room of Wrecking Crew musicians and string players to wear fireman hats while recording the manic Mrs. O’Leary’s Cow for Smile. Sly Stone, producing one of his own albums, had a nitrous oxide tank installed in his recording booth for… inspiration.

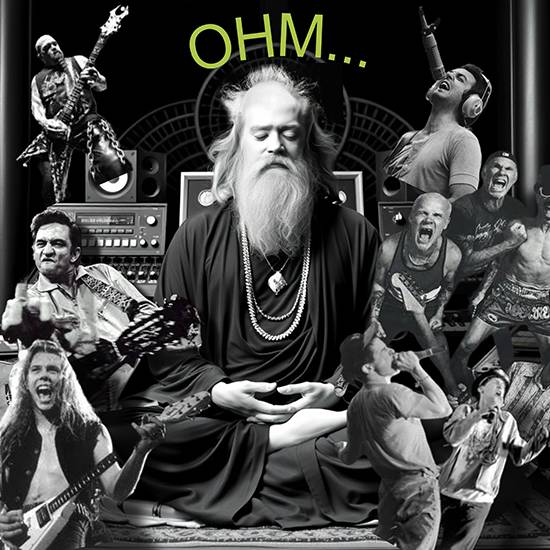

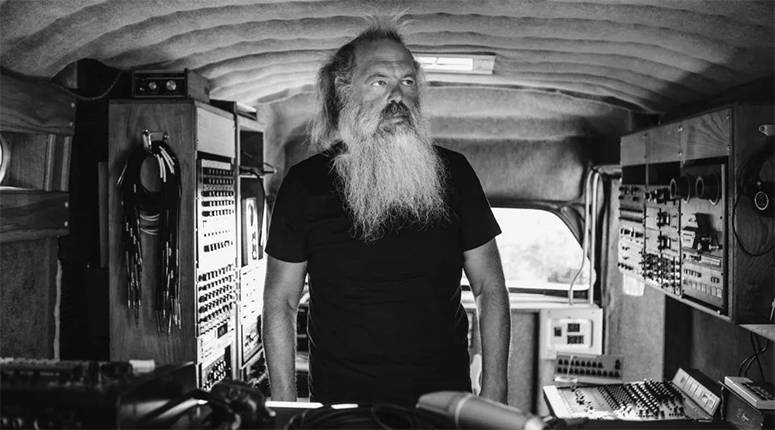

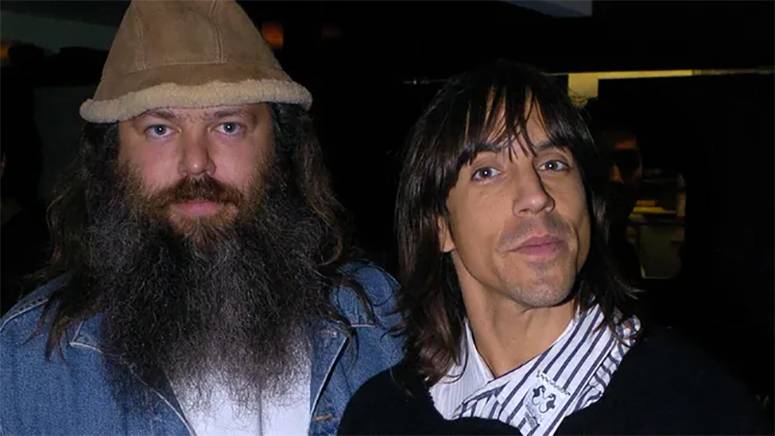

Then there’s Rick Rubin. The Def Jam founder is known for producing wild albums, fueled with rage or dripping with emotional angst—from the Beastie Boys to Red Hot Chili Peppers to Slayer—yet he comes on like a Buddha. All meditation and chill questions when inviting Paul McCartney to explore his own writing secrets in the TV series 3,2,1.

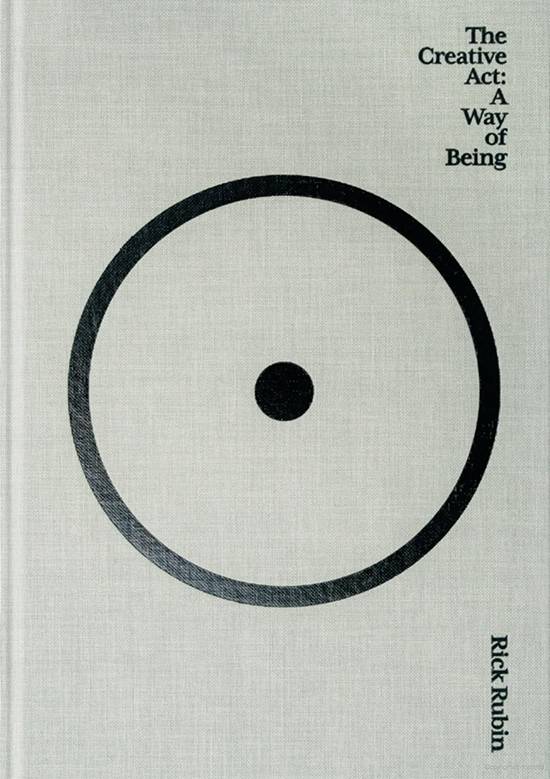

I landed on Rubin’s sand-colored, Zen-covered A Creative Act: A Way of Being and thought at first it was going to be a paper version of the “Calm” meditation app. It’s not. Rubin invites us—all of us—to look at ourselves as infinitely open creators. We all have similar tools available to us—senses, memories, experiences—but the artist finds a way to make creativity a practice. Whether commercially successful or not, there’s a yen for putting those practices into action, and bringing things to life.

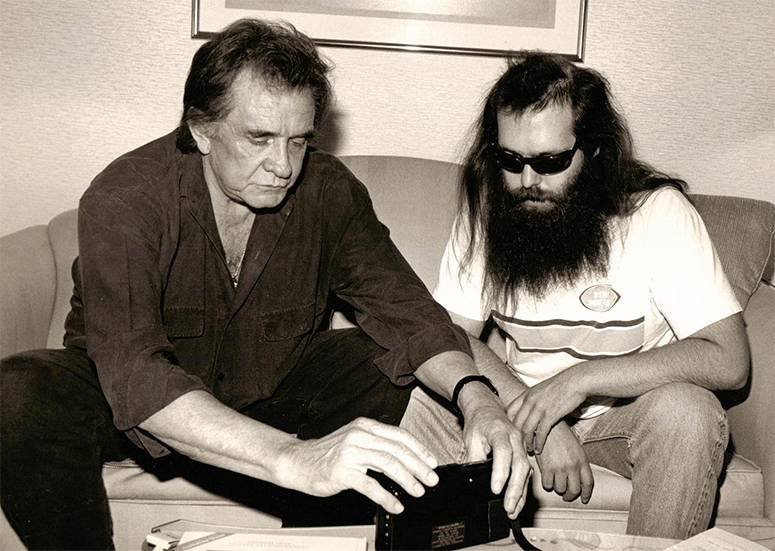

Rubin is a guru of sorts, and it’s helpful to leave all your preconceptions behind while absorbing the short, punchy chapters here. Yes, he resurrected artists like Johnny Cash, stripped them to the essence and hooked them up with songs by Nine Inch Nails. The results—on tracks like Hurt—were eerie, like light painting revealing the skeleton behind. Rubin’s recording practices are elusive and seemingly contradictory. Whether he’s stripping away sound, or building it up to clipped-and-compressed in-your-face levels, there’s a willingness to be the calm sensory switchboard in the middle, merely guiding the emanations forward, sending out pithy or inscrutable instructions to musicians (like telling Geezer Butler while recording Black Sabbath‘s 13 to “cast your mind back to when there was no such thing as heavy metal, and pretend this is the follow-up album to your debut”).

Like Brian Eno, Rubin favors coming at music or art from odd, unexpected angles. He doesn’t use “oblique strategies” or handcrafted card tricks, but Rubin will pass along suggestions to musicians to help them access their emotions, such as “beat on a pillow for five minutes. It’s more difficult than you might think to go the full duration. Time yourself and go hard. Then immediately fill five pages with whatever comes out.”

One presumes this worked on Anthony Kiedis while recording Blood Sugar Sex Magick up in Harry Houdini’s mansion. There’s a slight occultish tinge to Rubin’s guidance, which may have been misread or misunderstood over the years by musicians who tend to dabble in such things. Rubin might say it’s more about the yin and yang of nature: that for every light, there must be a shade of darkness. He believes in meditative, trancelike states as access points for “infinite data” from the universe. He shares this deep belief in meditation with filmmaker David Lynch, whose output is often unfairly interpreted as demonic or evil. Light and darkness, my friends…

Rubin has practical advice in A Creative Act: A Way of Being, methods to change the channel or find another radio frequency when approaching any creative task. Instead of looking at your current project as some kind of masterpiece-in-progress (no matter how excited you may be about it), lower the stakes: consider “moving forward with the more accurate point of view that it’s a small work, a beginning.” This must be invaluable advice for musicians facing the “sophomore slump.”

Dial it down. Come at it from a place of modesty, or mere fun. “If you start from the position that there is no right and wrong, no good or bad, and creativity is just free play with no rules, it’s easier to submerge yourself joyfully in the process of making things. We’re not playing to win, we’re playing to play.”

Another level he looks at is how creativity never needs to be a solitary effort. Collaboration occurs between us and nature, or between human collaborators. Ideas come from anywhere. We change every day as well, so our relationship with the work in progress changes. Sometimes we hate it, dismiss it, want to trash it. He calls this the “inspired-artist aspect” versus our need to be a good “craftsperson aspect.” What we are trying to do is close the gap between the exciting part of the creating, and our inner desire to shape the final output to something close to perfection.

I like that his advice can apply to any creative effort. You can take his ideas and apply them to writing a song, penning an essay, drawing or painting something out of the blue. His whole philosophy is built around becoming one with nature, which is a true and infinite conduit of information, and learning to channel it, carve it, shape it through our own impulses and personal filters.

All this stuff, when reading Rubin’s book, can seem obvious, or too “woo-woo” for some. But taken in small bite-size doses, the book is useful at uncovering truths we didn’t know we knew—or have forgotten we know—about creating things, perhaps emanating from some long-ago, faraway, infinite radio tower in the cosmos. Whatever works, it’s better than having a gun waved around in your face.