Context collapse in Vien Valencia's 'Bad Land'

Last year, the Bangsamoro autonomous region’s parliament filed the Badjao Development Project Act, a bill that intends to promote the rights and welfare of the seafaring Badjao tribe. Described by MP Adzfar Usman in his explanatory note as “one of the most vulnerable and marginalized indigenous groups in the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao,” the Badjao people, as a result of their nomadic roots and lack of formal integration as Filipino citizens, have faced myriad forms of oppression by social and institutional forces alike: forced displacement, police brutality, poverty, and more.

Scattered across Southeast Asia, the Badjao do not belong to one state nor possess an official nationality. In the Philippines, the Badjao reside in provinces around the Mindanao region including Sulu, Lanao del Sur, and Tawi-Tawi, and Basilan, but increasingly they have found themselves forced to relocate to cities in Metro Manila due to the decades-long armed conflict and state-sponsored violence occurring in Mindanao.

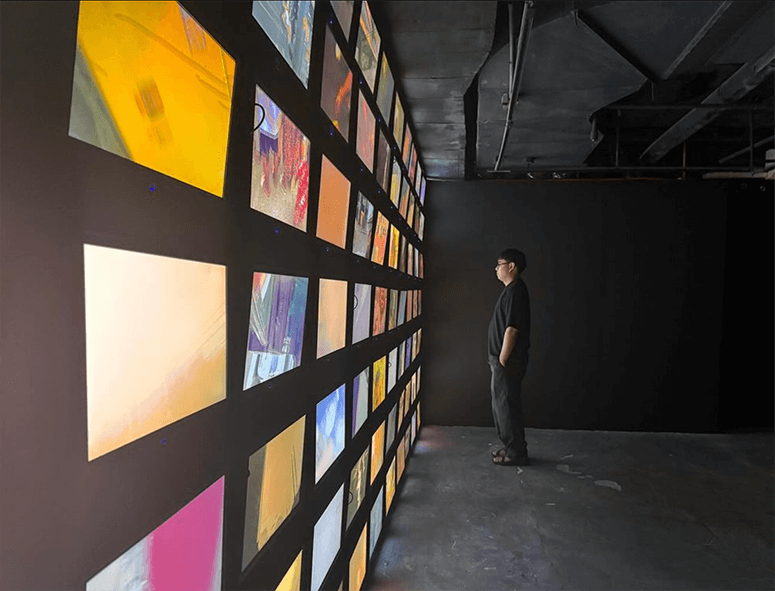

Vien Valencia, whose video and installation works are usually described as “collaborations with local communities,” exhibited “Bad Land” at Underground Gallery in Makati City, a show which takes up as its subject the displaced Badjao community in Metro Manila. “Bad Land” is a composition in two parts: In one room, we encounter a floor of woven mats, brimming with reverberant colors and complex patterns, eerily emptied of any description or annotation. By contrast, entering the neighboring room, which features a video installation screened through a grid of television screens, we are greeted by the sharp sounds of noise crackling through an unlit space.

The most crucial thing to note here is that all these videos playing in Valencia’s network of screens were taken by Badjao children. “Interrogating the multisensory environment and conditions of displacement,” the artist writes in a statement posted in the gallery, in the kind of elevated and detached air characteristic of contemporary artspeak, “the Badjao children were given the freedom to play with video cameras and were invited to film footage of their journey on foot in the urban landscape, enduring terrains of language and assumptions.”

It is a lot to take in, but what, concretely and materially, do we actually see? And how does what we see align with the vision of the artist to examine the Badjaos’ “conditions of displacement”? Mapped out like the control center of a surveillance unit, each screen plays coarse and restless footage captured by the Badjao children across various settings: narrow side streets, packed jeepneys, austerely lit supermarkets, congested roads. The children make their way through an unspecified city, interacting amongst themselves and with passersby. They tease, chase after each other.

In one scene, we see Valencia helping a child adjust his camera. Elsewhere, a pasty white foreigner looks genuinely unsettled as he’s filmed and followed. They approach policemen. As viewers, we catch bits and pieces of these strangers’ emotional responses, albeit fleetingly, from amusement and hesitancy to downright irritation. Absorbing the show’s chaotic structure, it’s very easy to feel overwhelmed, uncertain of where to position yourself amidst the disarray of visuals and audios. Captured with a frenzied velocity, the installation hardly gives space for any kind of thoughtful, intentional seeing. In effect, the overarching disposition of the work seems to capitalize on instability and disorientation over clarity and comprehension.

The installation’s hyperactive approach to representing its subjects calls into question the ethics of documenting the politically and systemically oppressed. What are we to make of all this chaos, orchestrated by Valencia but carried out by the labor of Badjao children? Beyond the messy experience of urban life, on what other terms are we to engage with these children whose lives are grounded on the threats and dangers of abject poverty? To what extent are these children able to give their consent towards this “collaboration”? Who, at the end of the day, benefits from this? There is a single name inscribed on the gallery’s glass doors, the artist’s name, and not one mention of a Badjao child’s name in the entire room.

Valencia chalks all these up to a mode of reasoning that relies on some grandiose, stubbornly theoretical inquiries. He asks: “What if the powerless became the watchers, wielding the gaze of scrutiny over those who once held authority? How would the dynamics of control and transparency shift in a world where the eyes of the marginalized pierce through the veils of privilege and secrecy?” This questioning calls to mind the generative process of resistance—the collective action towards overturning a political structure—but “Bad Land” is too conservative a work, too erratic and too incoherent to distill any kind of political statement.

Just as crucial in this equation, Valencia’s phrasing of “who once held authority” suggests an upsetting of the status quo. However, I’d wager that the show in actuality does the opposite of what it seeks out to do. Experiencing the video installation as a whole, I couldn’t help but notice a parasitic kind of invasiveness as these Badjao children, already burdened by the generational weight of poverty, violence, and social exclusion, are called upon to document the mundane hardships of their life. When Valencia asks what happens when the powerless become the watchers, he fails to acknowledge that, within the constricting frame of “Bad Land,” the watchers are ultimately, inevitably still us. Us: the public gaze consuming the video within the inscribed terms of an art institution, situated still inside its politics.

It is difficult to trace the politics of a work like “Bad Land,” which seems dangerously committed to an aesthetic of mystification. The show’s formal structure, impersonal and disorienting, has a strangely deadening effect: both rooms that encompass “Bad Land” enact their own forms of context collapse. The woven mats, exquisitely detailed as they are, appear without any attribution regarding their history, provenance, or process. Even worse, the video installation, smothered by simultaneity and stripped of any context, lacks any thread tying the footage together. Configured in a grid format, any specificity that can be drawn from each child’s footage is flattened into indistinguishable static. These deprivations of context critically diminish Valencia’s work—as well as any potential it has in building on its inquiries on displacement, surveillance and privilege.

One year has passed since the filing of the Badjao Development Project Act and we have yet to receive any word about the bill’s progress. The proposal is just one of many attempts advanced over the years to protect and preserve the Badjao community but at the moment it remains just that: a mere proposal. Despite the intention to bring about change, following through on the matter, especially when it comes to overturning these long-standing structures of oppression and exclusion, seems to be a whole other story. This unfortunate fact applies to “Bad Land,” whose documentarian impulses clash with its cacophonous, dehumanizing form.

A worthwhile collaboration, I believe, has to begin with acknowledging the topographies of power, agency and oppression, which naturally structure our interactions with one another. In its reticence to properly reckon with these topographies, “Bad Land” materializes as a guardedly disempowering work, in the service of aestheticizing a community’s struggle rather than truly engaging with the urgency of its stories.