On 30th anniversary of Nirvana’s ‘Nevermind’: An album forged by contradictions

Released 30 years ago this week, “Nevermind” was a generation-defining milestone that sold 30 million copies and made a tragic icon of Kurt Cobain.

Ranked the most influential band of all time by US magazine Spin last year, Nirvana’s ethos continues to reverberate in artists as varied as Billie Eilish, Lana Del Rey and Frank Turner.

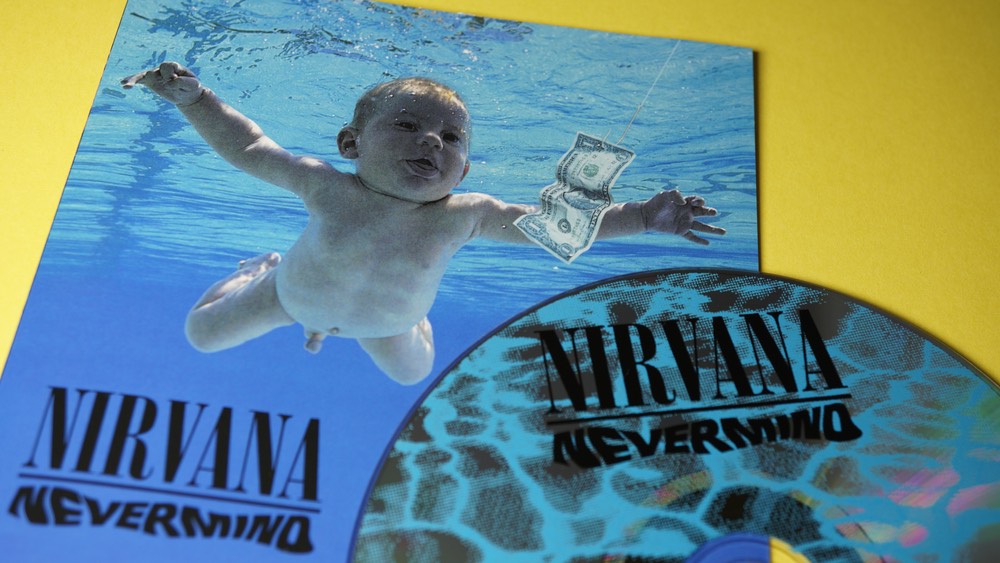

“Nevermind” was back in the news when the man who was photographed when he was a baby for the cover sued the band for sexual exploitation.

He was pictured naked, swimming after a dollar bill on a fish hook, in an image that became another iconic aspect of an album whose lead track Smells Like Teen Spirit was ubiquitous across MTV and radio stations around the world.

At the heart of the album’s success were the strange contradictions of Cobain, who was torn between apathy and rebellion, sweetness and rage.

Mainstream punk

“Nevermind” united musical tribes that had been largely separate —punk, indie, metal—and added a pop element that made them accessible to everyone else.

“It’s been building up through the years... Nirvana came along and delivered the goods,” said Thurston Moore, of fellow grunge outfit Sonic Youth, at the time. It was very pop but very honest and very authentic of the whole American punk rock ethic.”

In doing so, Nirvana made all the permed-hair, spandex-wearing posturing of 1980s rock look ridiculous. “It was the album that made hard rock obsolete -- the rock that was popular at the time: superficial, misogynistic, less intense,” Charlotte Blum, author of a recent book about the grunge movement, told AFP.

Reluctant ambition

Cobain was ambitious, his diaries filled with intricate plans, ruthlessly firing drummers until they found the perfect fit in Dave Grohl (now of the Foo Fighters). But the quadruple-platinum success of “Nevermind” was a nightmare for his punk-rock ethics.

He was traumatized at the idea that “yuppie scum in BMWs” were listening to “Nevermind,” and disowned its glossy production. “I haven’t listened to it since we put it out. I can’t stand that kind of production,” he told biographer Michael Azerrad.

Producer Butch Vig pointed out that Cobain had no problems with it in the studio: “If it had only sold 50,000 copies, he probably wouldn’t have had any comments on whether it was too slick.”

It ended in tragedy. Cobain’s suicide note was a long screed about the torment of “selling out.” But it was Cobain’s monomaniacal dedication to the punk cause that gave “Nevermind” such a ring of authenticity.

Ferocious nursery rhymes

From the immediately catchy riffs of Come As You Are and Lithium to the quieter anthems of Polly and Something in the Way, the sound was often furious, but the melodies simple—“like nursery rhymes,” Cobain said.

It was down to the fact that Cobain loved not just underground hardcore bands but also The Beatles, Abba and Queen. This combined with the raw power of Cobain’s voice which somehow encapsulated both joyous abandon and tortured adolescence.

Jay-Z said “Nevermind” was so successful at this that it stalled the rise of hip-hop. “‘Hair bands’ dominated the airwaves and rock became more about looks than actual substance and what it stood for: the rebellious spirit of youth,” he told Pharrell Williams in his autobiography.

“That’s why Teen Spirit rang so loud because it was right on point with how everyone felt. “Hip-hop was becoming this force, then grunge music stopped it for one second... when Kurt Cobain came with that statement it was like, ‘We got to wait awhile.’”

Apathetic activist

Crucial to the cult around Cobain was his anti-macho politics. “If you’re sexist, racist, a homophobe, or basically an asshole, don’t buy this CD. I don’t care if you like me, I hate you,” he said.

But while Cobain expressed disgust at the apathy of his generation, he also seemed to encapsulate an era marked by the end of the Cold War when political ideologies were dead and it was hard to know where to direct your youthful ennui.

In the end, he chose not activism, but a retreat from stardom, descent into drugs and ultimately suicide. As the song says—perhaps in mockery, perhaps in exhausted dejection—“Oh well, whatever, nevermind.” (AFP)