The passionate nationalist Adi Baen Santos

It is easy to love amidst the flowers, the sweets, and all the shine. But the brunt of what love is can often be hidden from sight; it is the part that needs to endure when the ugliness eventually surfaces.

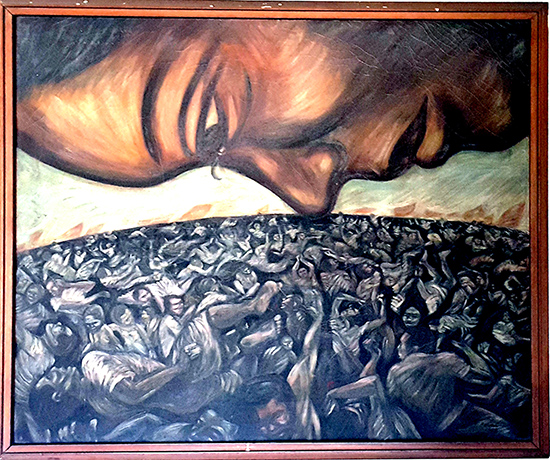

The Filipino nation that Pablo “Adi” Baen Santos reveals in his paintings is such: disheveled and in agony. One of his most known paintings is titled “Malumbay si Ina” created in 1983 during the last few years of Marcos dictatorship, and it shows a tearful mother looking over a mass of people whose bodies are contorted in pain. The work of Baen Santos (his real middle name was Baens, but he later dropped the ‘‘s’’) depicts the struggle of the working class: evocative scenes of everyday life rendered in bold brush strokes in high-contrast colors.

Adi‘s affection for the Filipino masses grew when he worked for The Manila Times during martial law. He developed bonds with journalists who participated in the underground revolutionary press that voiced out the struggles of workers, the urban poor, farmers, and marginalized groups and wrote about guerrilla ambushes and exposed evidence of corruption. This proximity with activist writers clearly manifested in his art. However, to choose to paint social realities at that time put him at grave risk since the then-current art market’s obsession was with “the true, the good, the beautiful,” which were mostly idyllic country scenes and quiet abstracts.

Adi‘s objective was to create art that would speak of the reality of the Filipino experience.

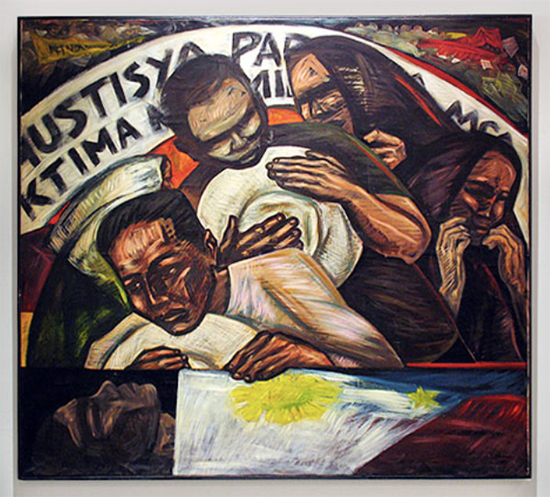

Despite the threat of cold reception, Adi and other artists knew that the working class needed to be seen. The artists found strength in assembling together in groups such as Artista ng Bayan, Concerned Artists of the Philippines, and Kaisahan that sought to collectively reveal what was under the sanitized facade of the “New Society.”

Adi was one of the founding members of Kaisahan and stood also as an elder brother to the younger artists of the group. Visual artist Renato Habulan recalls, “Adi helped me navigate this balance of survival and the call of our time — that is, to stand up against the tyranny of facism.”

He was also the one who drove the artists around for exposure trips and demonstrations and stayed with them even when times were grave: “Adi was a very kind person, he didn’t abandon us even when, after that noise barrage, my wife needed emergency attention and we brought her to the hospital despite the curfew,” added Habulan.

While writing the manifesto for Kaisahan, Habulan recounted that some scholars suggested taking cues from the cultural revolution happening in China, but Adi insisted on searching for the Filipino identity and the genuine aspirations of the people. Adi‘s objective was to create art that would speak of the reality of the Filipino experience. He said this in a panel discussion at Ateneo Art Gallery in 2017.

According to fellow artist Manny Garibay, what sets Adi‘s work apart from other social realists’ work is that it does not preach and instead focuses on the emotions of human struggle. His painting “Bagong Kristo,” exhibited in the National Gallery of Singapore, depicts an anguished Filipino bound to a dollar sign in lieu of a cross as though sacrificed in the name of capitalism.

After the EDSA revolution, political climates changed and the Filipino society shifted their attention to a range of urgent issues. In Adi‘s case he became preoccupied with philosophical questions and soon became an active member of a born-again Christian group. In a way, this shift to Christian practice continues carrying out the responsibility of social realism, which is to see the poor, sick and suffering and regard them with concern and kindness.

Adi passed away late last year, but his artworks remain relevant to the realities we face at present. By revealing the true conditions of a people, his work allowed for a more grounded affection for the nation. It demonstrates that love is inseparable from truth, and that truth is oftentimes inconvenient.

The works of Adi Baen Santos, along with other social realists such as Habulan, Al Manrique, Edgar Talusan Fernandez and Antipas Delotavo, are currently on exhibit again in the show “Ligalig: Art in a Time of Turmoil“ at the Ateneo Art Gallery until May 29. Physical visits are currently by-appointment only.