Haegue Yang in Manila

Found objects and fickle weather

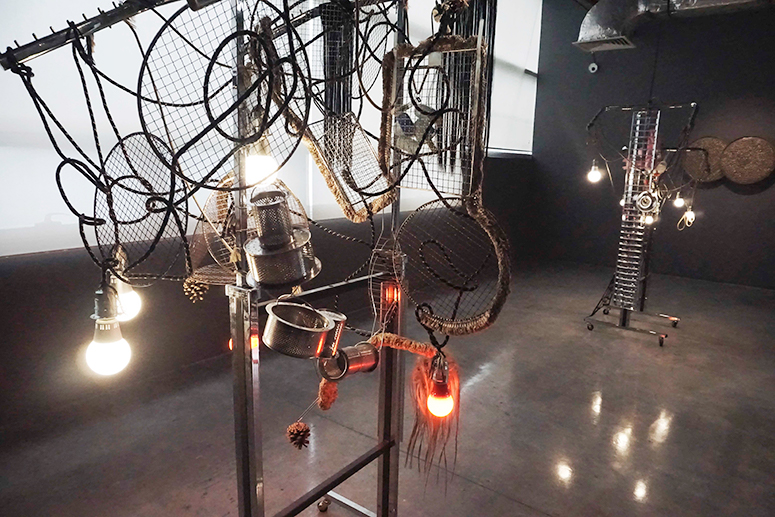

Haegue Yang’s assembly of found objects seems to follow the fate of this itinerant artist. At the Museum of Contemporary Art and Design (MCAD), our invigilator Bibi Belgica tells us about the large complex crates that carried Yang’s “Totem Robots” (2010) across countries.

Reassembled and made to stand upright, clothing racks on casters are once again bedecked with household items: cables are strung through grills, hairpieces hang beside plastic funnels. The arrangements are at once controlled and thrillingly unhinged.

It’s tricky to work with found objects. They seem to entail the never-ending tasks of extracting items from places, cleaning, shipping, reinstalling, and somehow putting them in dialogue with the current site.

The Cone of Concern, which is the artist’s first solo exhibition here in Manila, is an assortment of concepts and materials, much like a Haegue Yang reader.

“The Cone of Concern,” which is the artist’s first solo exhibition here in Manila, is an assortment of concepts and materials, much like a Haegue Yang reader. With an accompanying presentation of earlier works, it prompts us to trace where Yang’s interest in everyday objects and forms took root.

What greets us upstairs at the mezzanine are framed photographs of what Yang calls “sitting tables” in Korea. They are placed outside shops and residential buildings, in what she describes as “old-fashioned neighborhoods with narrow streets and little traffic.”

The artist catalogues them with earnest curiosity. One frame contains notes where Yang describes the social contexts in which the tables are embedded — possibly the same notes that, in a 2010 review, led the writer Ashley Rawlings to observe “the urban anthropologist in the artist.”

Yet, the bulkier stacks of field notes don’t seem to have much room in this exhibition. Here, the protagonist is material, and the instinctive playfulness by which Yang handles it, scatters it, or slices it, as in the case of “Cutting Board Print – Yellow Ginger #1” (2012).

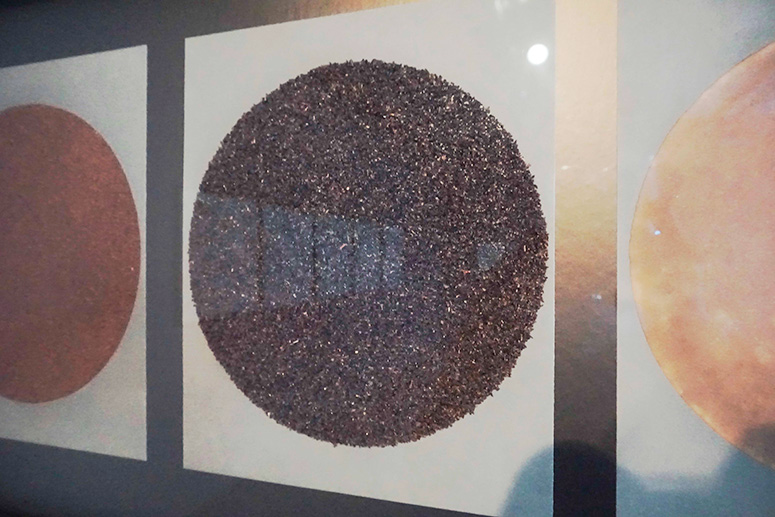

There is a nod to the space of homemaking. Consider the use of coffee, tea, and cacao grounds in the texturally arresting “Triptych Moon” (2013).

Somehow, these early works are intimate with place. The quadrilaterals in “Carsick Drawings” (2006) speak to a time during Yang’s residency in Japan when she responded to the inscrutability of newspapers by tracing the layout.

The drawings are straightforward, as if to show that lines, systems and grids aren’t always in the territory of minimalism; the wish to abstract is an everyday compulsion.

Throughout, I kept wanting to go back to this presentation upstairs. The earlier pieces suggest the roots of newer works, but they can also provide an interesting counterpoint. Texture upstairs invites close, unhurried inspection, and offers a bit more intimacy with marks patiently worked through.

Larger in scale, the new multimedia installations make us move around MCAD’s equally enormous space. A lenticular print sets off a mirage of images, one of the ways Yang tries to unsettle the impression of fine optical illusion.

Partitioning the space are wood structures resembling the binakol weaving pattern. The booklet text that accompanies the show briefly contextualizes this motif from the Ilocos region. Its pattern, drawn from wind, waves and whirlpools, is seen in contrast to the largely Western tradition of Op Art.

Once again, pattern is central in the “Randing Intermediates” (2020). The anthropomorphic sculptures are made of rattan and constructed through the titular technique of weaving a long piece of rod alternately over and under the stakes. Upright and on wheels, the “Inception Quartet” seems to have come from Yang’s line of “Totem Robots.”

There is no denying craftsmanship in its current guise (after all, Yang’s designs are executed by the artisans of S.C. Vizcarra). Though upon viewing these standing rattan totems, it’s easy to miss the refreshing laxness of the “Robots.”

The earlier pieces are less sculpture, more bricolage, more evocative of chance, defiance, and the everyday act of making do.

Textile, patterns and craft may perhaps be indicative of material heritage, but they also circulate within wide market economies, just as art does.

I’m led to wonder how the show could come to terms with culture’s contradictions. Or perhaps, how collaboration could somehow resist the template of artist-as-designer and artisan-as-worker.

Art-and-design and arts-and-culture may often come in pairs, but the affair between the two can sometimes be unwieldy. If found objects arise from a particular culture, with all its vibrant contradictions, its life force, how can one field not only join but complicate the other?

The artist is understandably at a remove from site and context, but the theme of the show does try to bridge the gap. The trope of weather, invoked in its title, runs through the exhibition. It shows up best as ambient energy: air blowing on cloth, AI murmuring from speakers, or the collective racket of bells sounding like short-lived morning drizzle.

Yet at various points when weather is translated more as faraway violence than vitality, such as when Yang puts together found images of cyclones and mushroom clouds, the effect seems out of touch. References to macro-events are dense but don’t seem to deepen.

For all the unruliness of weather, why must phenomena seem tamed?

Banner and thumbnail caption: The Randing Intermediate -Underbelly Alienage Duo (2020).

(The Cone of Concern runs until March 31, 2021. For appointments to visit the museum, go to https://www.mcadmanila.org.ph/visit/.)