Fernando Manso: Writing with light

The legendary photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson called photography “a way of comprehending.” And photographs, according to the late writer, critic and public intellectual Susan Sontag, “really are experience captured,” with the camera “the ideal arm of consciousness in its acquisitive mood.”

The work of the Spanish photographer Fernando Manso indeed reflects a considered, even painstaking practice of comprehension, and certainly captures experience in a way few other photographers have attempted, at least not in modern times. For Manso, through his poetic and atmospheric images, is more than a photographer clicking away at an object; focusing mostly on landscape and architecture, he is a crusader for heritage, a conjurer of histories, an artist who communicates through the motion of light through time.

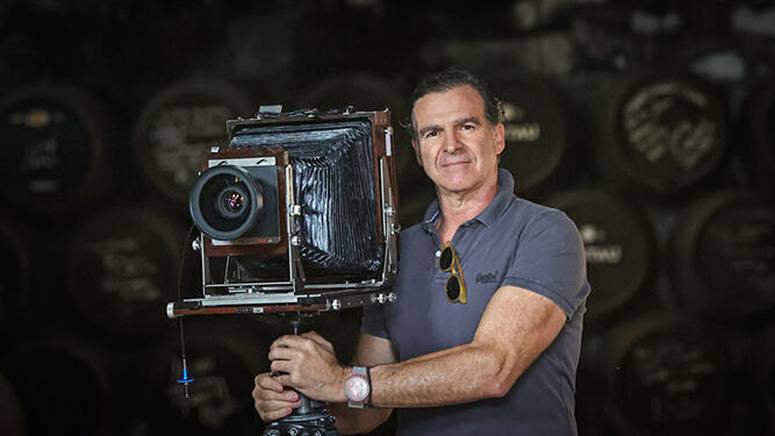

A former adman and son of an architect, Manso defines photography, in fact, as “writing with light,” going back to the word’s Greek roots— photos meaning light, and graphos meaning drawing. And his choice of instrument, a view camera that was first developed in the 1840s, is an anachronism in this age of technological wizardry, easy portability, and instantaneous delivery.

“My camera is a large, grand format camera mounted on a tripod that can go up to four meters,” he explains. “Then I take with me plates of negative color film that measure 20x25cm. All in all, my equipment is too heavy, between 30 to 40 kilos, and I go with all the material.”

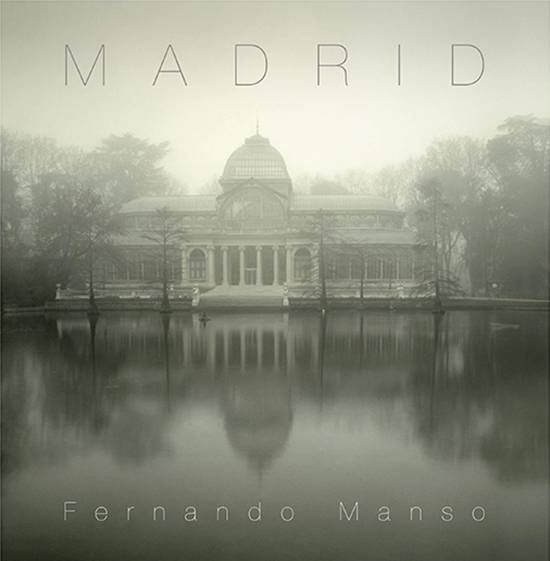

This clearly is not an endeavor for the faint-hearted, nor for the slightly built. At over six feet tall, Manso possesses the athletic physique that gives him the strength to carry his equipment with him as he treks through the remotest corners of his beloved Spain, walking along coastlines, trudging through desert, inching up mountains, setting up inside forgotten churches and abandoned monuments. But more than brawn, he possesses the mental stamina to wait patiently for hours, days and weeks, perched above his tripod, till the light is as it should be, and maybe —just maybe—the image in his mind is translated onto the glass plate, and later, in production, transformed into a large-scale photograph of breathtaking detail: an instant captured, not so much frozen in time but rendered in painterly beauty, resonant with poetry and shimmering with emotion. In its movement and stillness and truth, a story emerges, as his “Alhambra,” “España,” “Light of Spain” and “Madrid” series and accompanying books attest. Currently he is at work on a new series, “Whispers of Stone.”

His is a solitary practice. He works alone, driving cross-country in his Land Cruiser, without a team to carry his equipment. He laughingly recounts how in Colombia once, when speaking to the Spanish ambassador, who wanted him to present his Madrid photos in Bogota, he asked if he could take photos of Bogota to exhibit in Madrid. The ambassador thought it was a great idea, and offered to assign some young students to help Manso. “They were maybe 18, 20, 21 years old. Every day, they had to change the student because they couldn’t continue for 12 to 14 hours with me, without food or water. One day, one guy, he was lying on the floor. I said, ‘What are you doing?’ He said, ‘Because we started at 4 a.m. and it’s now 5 p.m. and we haven’t eaten anything.’ But this is how I work. They were expecting one hour, two hours. They didn’t understand.”

And yet Manso is hardly the cruel taskmaster; in reality, he is exacting in standards, but gentle in nature, much like his old-school approach to photography. What happens when he is at work, observing the minute changes in the way the light falls, the atmosphere compresses, or the weather intensifies, thereby impacting the image that may emerge, is that he gets into alpha mode, on a level of mind control similar to that of meditation in which everything that is extraneous does not matter. When he’s in the “zone,” so much, in effect, is an act of faith as all he has is a single plate for each shot, with an inkling, but no certainty, as to how the photo will turn out as there is no such thing as digital playback in his artisanal approach to his craft. It’s no wonder he has been called “the most patient man in the world.”

“I can’t really explain why I work the way I do,” he confesses, “even when it comes to the size of my photos once printed. It’s just something I feel in my heart.”

Also in his heart is the Philippines, a country he has been visiting regularly for 13 years, thanks to his long-time love, Bea Zobel, Jr. He has sought to capture the beauty of our islands with his view camera, but considering the way he works, he would understandably need more time to watch the movements of the sun and the sky, in order to mark, as he does with his photographs of Spain, “the passage of time.” Batanes is on his wish list.

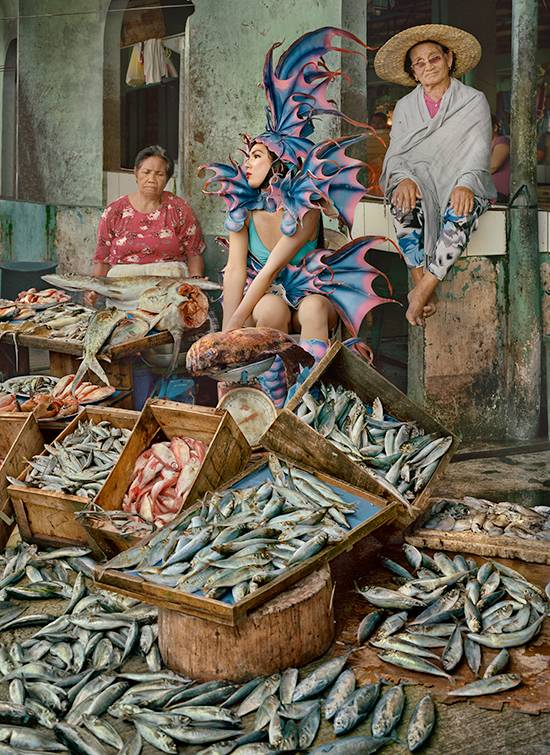

In October 2022, I curated my first museum exhibition, “The Hat of the Matter,” at the Metropolitan Museum of Manila as part of its inaugural offerings at the new location in BGC. Taking liberties with the theme of hats and headgear and their significance in Philippine society, whether as signifiers of status or barometers of style, I was determined to include a photograph of Manso that I had seen a few years back. From the moment I saw it as an Instagram post, I was mesmerized. But nothing prepared me for the sheer power of the real-life oversized print I hand-carried back with me from Madrid in time for the exhibition.

In the wall text that accompanied the exhibition, I wrote:

“On a trip to Cebu in 2016, Fernando Manso set about photographing transgender women in various locales around the city. The idea was to situate them within everyday scenes while emphasizing the aspect of performance and spectacle that was so much a part of their professional personas. Flamboyant hats and headpieces, then, become central to their performance. The fantastical headpiece here, evoking an iridescent sea creature—a mermaid, goddess, or a beautiful manta ray, even—emerging from the depths of the ocean, brings an unexpected frisson of glamour to the fish market, transforming it from the mundane to the theatrical.”

Whether he sets his eye on crumbling monuments and Gothic cathedrals, or grassy fields and silvery lakes, Manso imbues his subjects with deep awe and reverence for their natural beauty, the secrets within their arches and waters, and the histories contained in them. With his photographs of human subjects, he does the same, allowing their humanity to glow from within.