The language of hair

PARIS—Hair would initially appear to be a mundane subject, but next to our faces—and even before what we’re wearing—our hair is actually the most important part of our bodies when presenting ourselves to the world.

Just like clothing and accessories, hair and body hair have been active participants in the social construction of our appearances for centuries, a premise that the Museé des Arts Decoratifs posits in the exhibition “Des Cheveux et des Poils (Hair and Hairs),” a continuation of its exploration of the relationship between the body and fashion.

As an essential aspect of our identity, hair has often been used as a means of expressing our adherence to trends, to a set of values or how we challenge or reject values in place, while invoking much deeper meanings such as femininity, virility, and negligence, to name a few.

Unruly locks or excessive body hair have often been associated with a wild animality, leading to a culture of taming it to distinguish the woman or man from the beast. Styling one’s hair was both a social indicator and a marker of identity. In medieval Europe and into the early modern period, most women covered their heads with a veil, hood, or headdress when outside the home, conforming to norms established in the Bible by Saint Paul’s first letter to the Corinthians.

You couldn’t keep all that good hair down, however, so by the end of the 15th century, as seen in portraits, veils and high headdresses were progressively replaced by simple velvet hairpieces and hair was increasingly seen uncovered. Even when it was covered, hairstyles already took unexpected directions, like in a 1468 portrait of Marguerite d’York, where her hair is pulled up and covered with a conical hairpiece over which a veil was draped.

By the 16th and 17th centuries, hairdressers went wild as feminine hairstyles became a function of fashion, ruled by precise conventions. It is from this time that extravagant coiffures developed, presenting a living tableau of 400 years of some of the most inventive things one could do with our crowning glory. These styles also had a language of their own.

All the rage in England in the early 17th century was the love lock, strands of the significant other’s hair worn as an earring, preferably worn on the left side where the heart is, as seen in the portrait of Elizabeth Stuart, Queen of Bohemia.

Madame de Sevigné set a trend with her “little cabbage head” hairstyle, which she mentioned in a 1671 letter. Describing it as hurluberlu (brusquely, lacking in consideration), the term would be associated with the style that replaced the demure curls that until then had framed the face.

Named after the mistress of Louis XIV, the fontange, which started with the Marquise tying her hair up with a ribbon, developed into a tall, elaborate style where the front of the hair was curled and piled high above the forehead in front of the towering lace frelange headpiece requiring a wire framework for its skyscraper architecture.

Abandoning the headpiece while keeping the height, the tape, or high roll with a crinoline cushion, was adopted, growing higher and higher and more complex, reaching its apogee in the 1770s.

A revolutionary, cropped style called the “Titus” would emerge from between 1795 and 1810, sported by a few audacious women like Madame Fouler, who looks as modern as a woman of today in an 1810 portrait. The origin of the coif seems to be the “Victims Balls” reserved for people with relatives whose lives were cut short by the guillotine. A witness recounted that some of the balls required that attendees “cut their hair short around the neck, just as the executioner cuts the hair of victims of the revolutionary tribunal.”

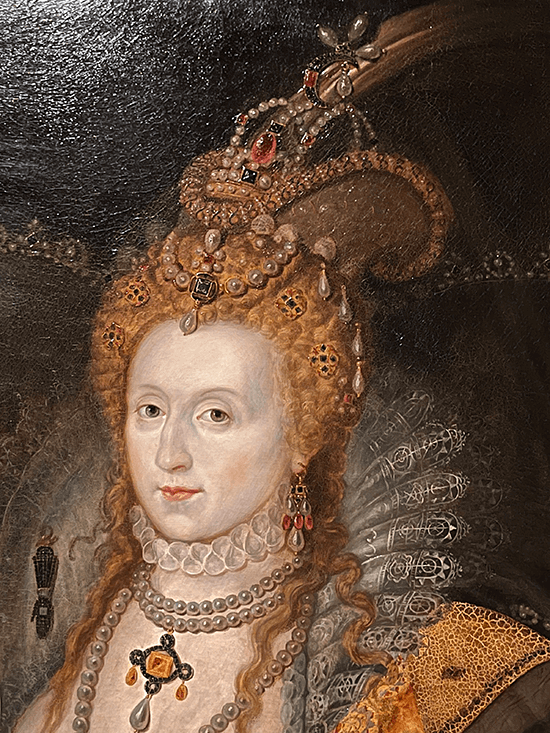

We cannot talk about hair without the ornaments that decorated it, a whole universe of customs, beliefs and symbolisms. Elizabeth I’s portrait eloquently portrays the allegorical and metaphorical role these embellishments play: while the pearls signify the queen’s virginity, the crescent moon displays her political and maritime power—identified with Cynthia, Greek goddess of the moon and empress of the oceans, an allusion to the monarch’s prowess on the high seas in battles against the Spanish Armada that attempted to invade England in 1588.

Tiaras, combs and hairpins were considered essential to tame a woman’s hair which, in its natural state was considered both inconvenient and a sign of animality, even lustfulness. A rare portrait of Empress Elizabeth with her hair falling loose over her chest was commissioned by her husband, Emperor of Austria Franz Joseph, but for his eyes only, viewed in his private quarters.

The empress Sissi was famous for her hair that touched the ground, requiring the whole morning for “The Great Wash.” Witnesses recounted that hair that fell out while being styled was presented to her on a silver platter by her hairdresser, who prostrated herself at Sissi’s feet.

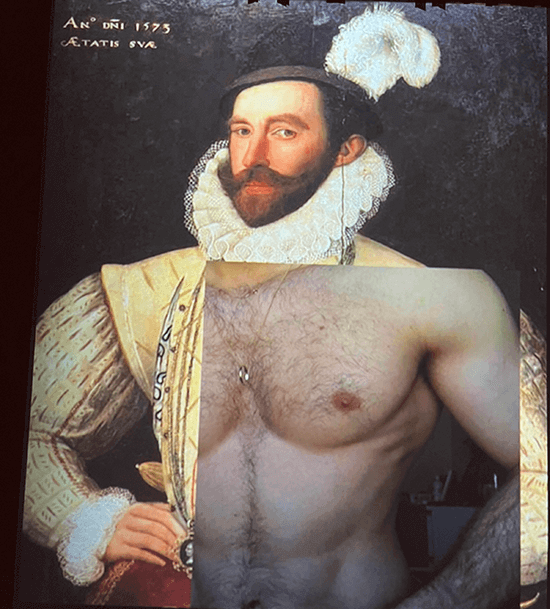

Men’s hair is another story altogether. In the Middle Ages, hairless faces were seen, but by the 16th century beards appeared with Francis I, Henry VIII and Charles V wearing them, associating the style with the warrior spirit and virility.

From the 1630s until the end of the 18th century, the hairless face and the wig were hallmarks of courtiers. Facial hair only reappeared in the early 19th century with the mustache, sideburns and beard requiring a multitude of objects used to maintain them.

The cleanshaven look of Hollywood stars like Gary Cooper in the 1930s would promote a clean, shaved look, while the ’70s hippie and gay culture would promote facial hair again. The beard would also be revived by hipsters in the 1990s. in 2007, the moustache returned as “an affirmation of virility in the face of the supposed feminization of men,” according to the magazine Monsieur.

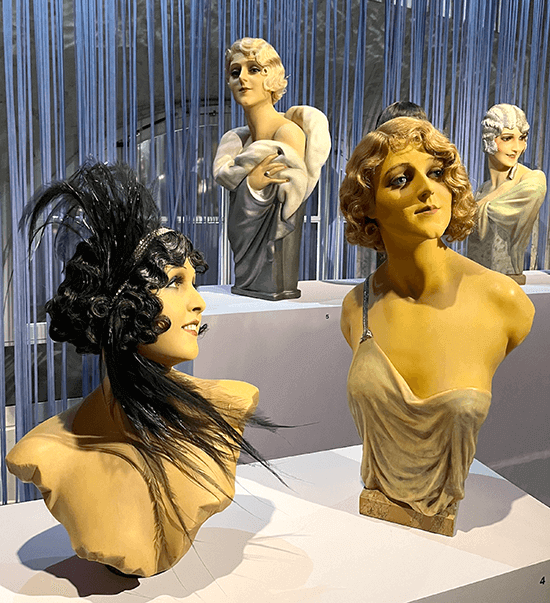

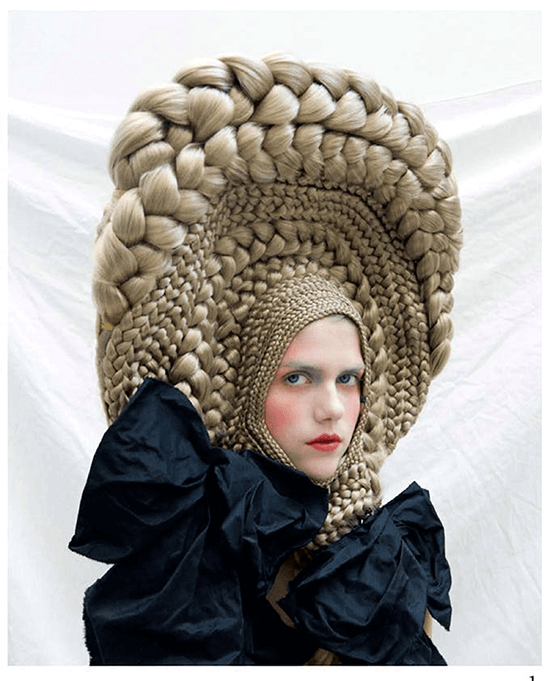

An evolution of hairstyles from the 1900s chignon, the 1920s garçonne, the 1930s permed and notched cut to the 1960s pixie and sauerkraut, the 1970s long hair, the 1980s voluminous Dynasty poufs and the 1990s gradation and blond streaks show how historical events have influenced styles and how hair has gone a long way from Biblical times, even transforming into garments and fashion objects, as seen in the creations of contemporary designers like Martin Margiela and Josephus Thimister.

Then, as now, identity and personal expression remains at the heart of whatever it is we do with hair.