Olé to flamenco fashion

Mention Spain and flamenco no doubt comes to mind—the rousing rhythms from the guitars, the cajón, clapping hands and the singer’s cry accompanying the sinuous, sensual movements of a flamenquera; and her dress, of course, dramatically hugging her figure before erupting into a cascade of ruffles below, creating their own flourish that is part and parcel of the dance itself.

Flamenco comes from “fire” or “flame,” conveying the fervor and fury at the heart of the dance.

Integral to flamenco is duende, a heightened state of emotion, expression and authenticity first articulated by Andalusian poet Federico Garcia Lorca as “irrationality, earthiness, a heightened awareness of death, and a dash of the diabolical.” Duende seizes not only the performer but also the audience, creating conditions where art can be understood spontaneously with little, if any, unconscious effort.

Based on various folkloric music traditions of the south and developed within the gitano subculture of Andalusia, the dance is closely associated with the gitanos or gypsies of the Romani ethnicity who have contributed significantly to its origination and professionalization, which is why the traje de flamenca is also known as the traje de gitana, or gypsy outfit.

Aside from performances, the dress is traditionally worn at Andalusian ferias or festivals as a day dress, which is close to the body till mid-thigh before flouncing into multiple layers of ruffles to the ankle. Starched underskirts give volume just as crinolines would. The dancer’s version flares out from higher on the hip to allow freedom of movement. Both are trimmed with layers of ruffles both on the skirt and the sleeves and are typically boldly colored in red or black and sometimes patterned in the favorite polka dot-printed traje de lunares.

The outfit is accessorized with a manton de Manila worn over the shoulders. Made of silk and embroidered with floral motifs, this colonial-era shawl was popular in the Philippines, Latin America and Spain. It was derived from the panuelo of our traje de mestiza, the precursor of the terno.

Originally embroidered in piña and other fabrics, they later came in silk from Canton and became luxury exports to Europe and the Americas through the Manila-based Galleon Trade. A lace mantilla is draped over the hair, which is usually done in a low bun adorned with a large comb or small combs made of tortoiseshell or mother of pearl, with natural or artificial flowers.

The origin of the dress is quite humble, as peasants and gypsy women wore a robe with ruffles to do their chores in the 19th century, although the oldest record of flamenco music dates back to 1774 in the book of Las Cartas Marruecas by José Cadalso. The frilly coats, sewn at home, were worn by the women when accompanying their husbands to the April Fair in Seville in 1847.

What started as a cattle fair evolved into a fiesta and these ruffled dresses became more elaborate with colors and embroidery. They would be romanticized by writers who dedicated themselves to the idea that “In Andalusia, misery has always been dressed fancy.”

Bourgeois ladies were attracted to the ensemble and began to do their versions with more exclusive and delicate elements. Slowly, the dress became the garment of choice to go to the fair and from 1929, at the Iberico-American exhibition, its use became “official,” thanks also to the professionalization of flamenco, which took this outfit as its own.

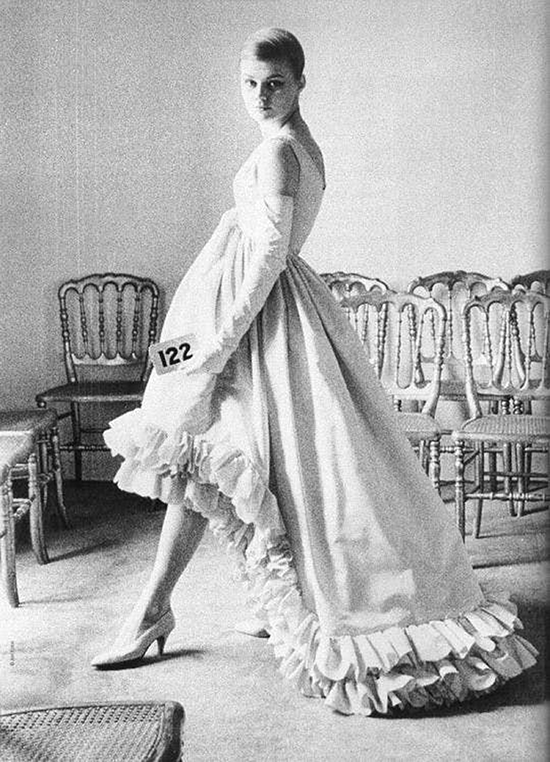

It would undergo changes through the years: In the 1950s, it was adorned with ribbons and large satin bows, bulky sleeves, and a shawl draped across the chest. In high fashion, however, they were distilled to their essence, like the way Cristobal Balenciaga referenced flamenco through his sculptural couture pieces that were all the rage in Paris.

Hubert de Givenchy, who looked up to the Spanish couturier, was also captivated by the costume and created the 1952 “Bettina Blouse,” named after top Italian model Bettina Graziani. With tiers of ruffles down the sleeves of the cotton top adding drama and a whiff of Spain and its fabled dance, the Bettina is a key piece in the French designer’s first collection of separates—couture with a modern approach that presaged prêt-à-porter. Citing his mentor in an interview, Givenchy explained, “A ruffle must be intelligent.”

The 1980s overloaded the costume with many more ornaments and patterned fabrics while narrowing it to a more seductive shape with emphasis on the neckline and the hips.

In the ’90s, minimalism would set in again, leaving aside ornamentation as a new concept of the dress was created—more ethereal and sensual.

In the 21st century, flamenco continues to be a rich source for designers, from American greats like Ralph Lauren and Oscar de la Renta to Italian darlings Dolce & Gabbana and Alberta Ferretti, as well as classic French houses like Balmain and Dior.

For Dior’s Resort 2023 collection, the show was set in Seville, on a stage held by two black-clad gypsy flamenco stars, 40 dancers and 110 models parading against the backdrop of the Plaza España.

Immersing herself in the traditions, crafts, histories and female heroes of Andalusia, creative director Maria Grazia Chiuri singled out Carmen Amaya, known as “La Capitana” in the 1950s—the first female flamenco dancer to wear men’s clothes. The inspiration resulted in the perfect device to channel the designer’s vision of androgynous, feminist dressing, which was seen in romantic but restrained references to the off-the shoulder, flounced flamenco dresses in taffeta, and subtle layers of darkly sexy lace, black leather and arabesque prints.

Working with ateliers in Southern Spain, she has brought the traditional flamenco dress to the current century by updating the design as well as the artisanal skills related to it.