Fashion diplomacy in Bangkok

The pause before the applause was telling.

It marked intention, not overstatement.

In Bangkok, Lahi 2026 unfolded with clarity, positioning Rajo Laurel not just as a designer but as a fashion diplomat for Filipino creativity.

The choice of setting sharpened the message. Presented outdoors at Dusit Thani Bangkok, with Lumpini Park as backdrop and the Bangkok skyline settling into dusk, Lahi unfolded in a space that felt deliberately open—heritage allowed to breathe within a contemporary cityscape. Nature, city and fashion shared the same frame, reinforcing the idea that lineage does not belong behind glass but in the present.

Bangkok Design Week is not a traditional fashion platform. It is a design-led environment where creativity is treated as both cultural expression and economic language. To present Lahi within this framework was a resolute move. It placed Philippine fashion within a regional conversation about value, authorship, and relevance rather than novelty.

That positioning was reinforced by clear and decisively paced government support through the Department of Trade and Industry’s Malikhaing Pinoy program, reflecting the Marcos administration’s commitment to advancing the Filipino creative industry as both cultural capital and economic strategy. Presented with the quiet imprimatur of Cristina Roque, Secretary of Trade and Industry, the support was neither ornamental nor incidental. By anchoring Lahi within Bangkok Design Week, the administration signaled an understanding of where Filipino design belongs—within regional conversations on trade and contemporary relevance.

Malikhaing Pinoy is the appropriate considered approach rather than symbolism. The DTI has positioned Filipino fashion as soft power.

The collection itself reflected that confidence. Lahi, a word that speaks to lineage and inheritance, unfolded through a tightly edited yet robust 33-piece couture collection that felt mindful and wearable. Filipino elements and fabrics were brought together with care, resulting in garments that felt cohesive rather than referential. Nothing slipped into costume. These were clothes designed to move, to be worn, to exist beyond the runway—heritage integrated into form rather than placed on display.

What stood out was the restraint. Against that open Bangkok sky and a city settling into evening, restraint read as authority. The garments did not rely on the obvious or explanatory gestures. Filipino identity was present as an undercurrent—felt rather than announced—embedded in material choices, proportion and continuity.

At one point, a Thai creative seated nearby leaned over and remarked—almost casually—that what struck them most was how the collection moved past the usual shorthand of “Filipino” fashion. There were no terno butterfly sleeves to explain, no barong to translate, they said—yet the identity was unmistakable. It was a small observation, offered quietly; and precisely because of that, it lingered.

Laurel treated the collection as a single argument rooted in material and finish. Fabrics were chosen for how they behaved on the body—how they held, folded and moved—allowing Filipino references to emerge through texture and construction rather than symbol. The result was work that did not depend on familiar silhouettes to be legible, proving that identity, when fully internalized, needs no translation.

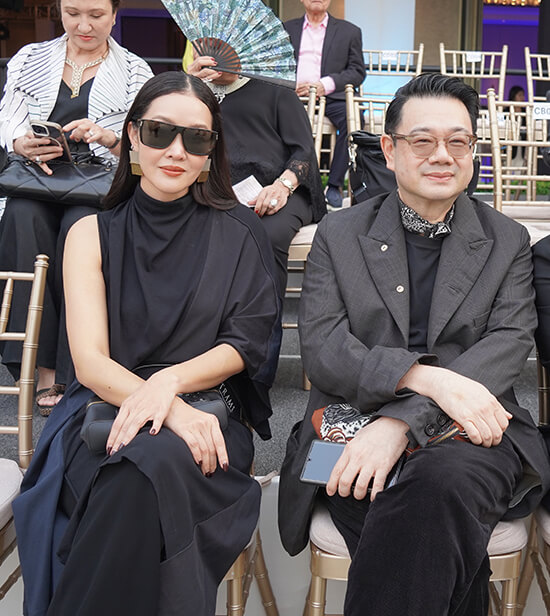

Malou Gamboa, Sen. Grace Poe, Nix Alanon, Ana Martha Moreno, and Mond Gutierrez

The response from the audience mirrored this sensibility. There was clear through-line, not frenzy; engagement, not applause on cue. Lahi did not overwhelm; it held attention. In a city attuned to design rigor, Laurel’s work felt legible and assured. It suggested that Philippine couture, when approached with clarity, belongs naturally in regional and global conversations—not as novelty but as practice.

What makes Laurel particularly effective in this role is not only his design sensibility but his understanding of the Filipino—how we move, how we dress, how we carry ourselves. He is articulate without being didactic, rooted without being nostalgic. Just as importantly, he understands the business of fashion: how collections travel, how markets read design, and how work must be positioned to resonate beyond home. That combination—cultural fluency, clarity of expression and commercial intelligence—is what makes his representation credible on a regional stage.

This moment carries added resonance when viewed through Laurel’s own lineage. Coming from a family of statesmen and public servants, his instinct for representation feels earned rather than assumed. The idea of carrying the country—of standing for something larger than oneself—has long been part of his inheritance.

Seen in this light, Lahi reads as a contemporary expression of service, rendered not through policy or speech but through design.

In this sense, what unfolds through Lahi is a quiet exercise in soft power. Laurel does not speak on behalf of the Philippines through statements or slogans. He represents through coherence, wearability, and restraint. This is what a fashion diplomat looks like today.

Lahi makes a simple, confident case: Filipino fashion does not need to announce itself to be taken seriously.