Pierre Cardin: Visionary or cautionary case study?

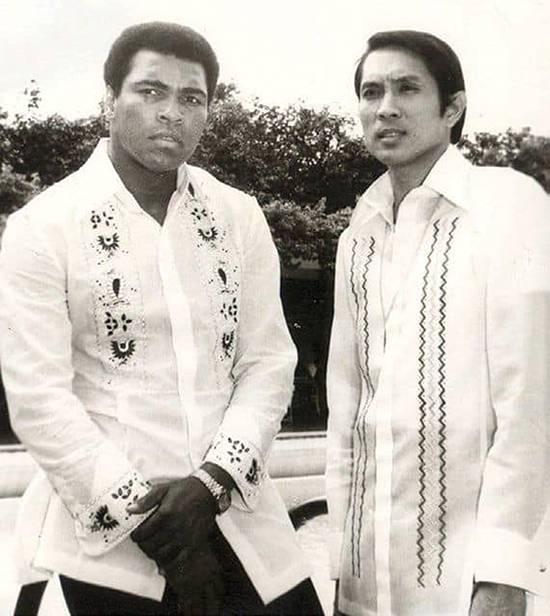

A barong was actually named after Pierre Cardin in the early 1970s, the most copied style after it was created by his atelier in Manila. Yes, the Paris-based house had a branch here, which was quite a big deal since the Italian-born French designer was at the height of his fame and even sent the young Jean Paul Gaultier, who would become one of the world’s foremost designers. Gaultier worked in the Manila shop together with Giovanni Sanna, an Italian who later made the Philippines his home before returning to Italy in 2008 to become a monk.

The presence and influence of Cardin all over the world made him one of the most recognizable names in fashion, coming way before the frenzy for globalization in the 1990s that triggered unprecedented connectivity after the post-Cold War era.

The Pierre Cardin barong innovated on the traditional design by opening the front to button down all the way, tapering the body, removing the cuffs that required cufflinks, flaring the sleeves and minimizing the embroidery. The modernity reflected the style that he developed as he traversed the world and facilitated a cross-pollination—rom his lectures in Japan and visits to China to his shows in Paris and Moscow. He always picked up on the cultures of places he visited but gave a futuristic spin to his creations. “The dresses I prefer,” he said then, “are those I invent for a life that does not yet exist, the world of tomorrow.”

He naturally became the poster boy for the Space Age movement in the 1960s, although he had always been a forward-thinking designer. Born in 1922 in San Andrea de Barbara near Venice, Cardin and his family moved to France in 1926. His wine merchant parents wanted him to become an architect but his aptitude for fashion already showed at age eight when he started designing dresses for neighbors’ dolls and by age 13, he apprenticed for a tailor in Vichy.

In 1944, he joined the Red Cross to go to Paris, where he was able to get a job with Paquin and Schiaparelli. During this time, he also became a costume maker for the 1946 film Beauty and the Beast by Jean Cocteau. That same year, he became the master tailor of Christian Dior, where he worked on the groundbreaking New Look collection.

Cardin decided to set up his own label in 1950, launching his career when he designed costumes for the 1951 masquerade ball of Carlos de Beistegui in Venice. He remained a protége of Dior, who asked him to design his lion costume for the ball and always sent overflow clients his way. Cardin, in fact was a strong contender to replace Dior after his death, with the senior designer saying then that “Designers like Pierre Cardin are the future of haute couture.”

After moving to an 18th-century mansion on Rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré, he presented his first couture collection in 1953, opened his first women’s boutique called Eve in 1954, and the men’s version, Adam, in 1957. This decade established him as an enfant terrible, attracting the likes of Rita Hayworth, Eva Peron and The Beatles as clients.

He gained further notoriety in 1959 as the first haute couture designer to launch a ready-to-wear line, resulting in his expulsion from the Chambre Syndicale. He explained his move, which was both philosophical and pragmatic: “It was my desire to make my creations accessible to a greater number of people by bringing high fashion to the street. For me, fashion should not be a privilege. And if you are going to be copied, might as well do it yourself.”

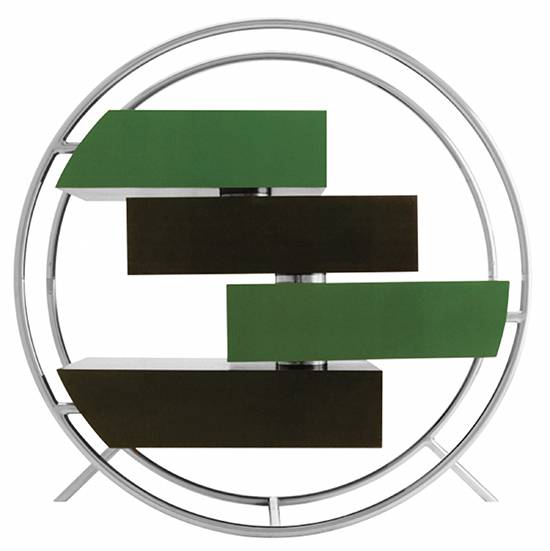

Realizing that a fashion brand’s glamour had endless marketing potential, he made an even more audacious move in the 1960s by licensing his name and initials, emblazoning them on a wide range of products, from clothing to interior design to cars and airplanes. He had an acute grasp of the zeitgeist, seeing how fashion was not only becoming more democratic but pluralistic and individualized as well, stating that “It would be insane to lengthen skirts just to follow an up and down cycle. It is ridiculous to change the silhouette every six months.”

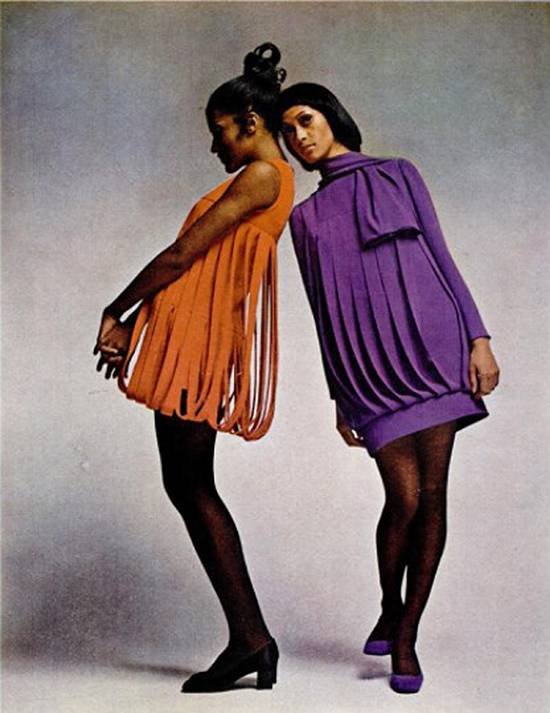

What he proposed instead were alternative visions of fashion made from new fabrics and reimagined silhouettes, exemplified by his 1964 Cosmocorps collection, a precursor to today’s gender-fluid fashion, often worn by Japanese model Hiroko Matsumoto, who embodied the “purity” that he wanted to achieve in design. Collarless or roll-neck tops, jumpsuits and unitards worn as basics underneath skirts, elongated vests, codpieces, outsize jewelry and plexiglass visors heralded the Space Age look, which became all the rage as it resonated with visions of an inclusive future, as seen in science fiction films and TV series like the 1966 Star Trek that featured similar costumes and in the space race between the US and USSR. Cardin even visited NASA in 1970 and was asked to design spacesuits.

Licensing the Cardin name, which reached a peak of 850 licenses in over 110 international boutiques, made Cardin “probably Europe’s wealthiest designer,” according to a 1986 WWD article. It afforded him the creative freedom to develop his couture and have his shows without following the prescribed fashion week calendar. He also pursued other interests beyond fashion: theater, furniture and industrial design, cuisine, architecture and humanitarian efforts.

The downside was that the brand became diluted, plastered on everything from pickle jars to key chains, losing a lot of its luster. He tried to supervise every license granted but it just went out of hand, especially in countries where copyright laws were not enforced.

His work ethic and curiosity about what was next and what was in our future continued till 2020, the year he died on December 29—going to the office each morning and designing, even at age 98. Three months before he died, after a bout of COVID, he told a reporter, “After my death? I don’t think about it. I didn’t organize anything. Nothing.”

He stood steadfast till the end, hands-on, independent, with absolute control. His great nephew, Rodrigo Basilicati-Cardin, took over the house but without a signed will, the family is fighting over ownership and what to do with the company. Unlike during Cardin’s lifetime when he was confident about the future, in death, nothing seems certain at all.