Madame Grès: The sphinx who sculpted fashion

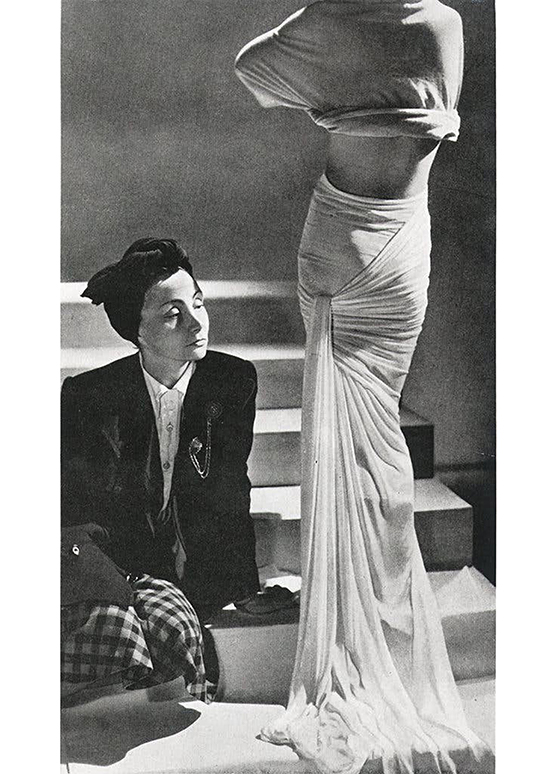

Madame Grès is probably the most mysterious of the great designers of the 20th century, extremely secretive about her personal life, rarely granting interviews as she gained the reputation of being “a workaholic with a furious attention to detail.”

She preferred to let her work speak for itself. And it indeed spoke volumes: divinely sculpted gowns of masterfully draped and finely pleated silk belying subtly hidden couture techniques requiring insane quantities of fabric and handiwork that elevated craft to the level of art.

Displayed at exhibits, they stand like otherworldly Greek statuary of goddesses that had always fascinated her.

Born Germaine Émilie Krebs to a French-Jewish family in 1903, she was raised in Paris where she studied painting and sculpture and in fact dreamed of being a sculptress but objections from her parents shifted her path to fashion instead, training in haute couture dressmaking at Maison Premet.

In 1932, she changed her name to Alix and opened La Maison Alix, her own couture house. She joined Juliette Barton of La Maison Barton as assistant designer in 1934 and gained recognition for her designs prompting the renaming of the house to La Maison Alix Barton.

The New York Times at one time called her couture house 'the most intellectual place in Europe to buy clothes.'

In 1937, she married a Russian painter named Serge Czerefkov and changed her name again to Grès, an anagram of “Serge” and a name that she would keep and be known for.

World War II and the invasion of France in 1939 found her pregnant but Serge abandoned her before the birth of their daughter whom the designer named Anne. Anne is raised with the assistance of Muni who became a godmother and lived with Grès for more than 40 years causing speculation about their intimate relationship.

In 1941, Grès sold her stake at Alix Barton and opened La Maison Grès where her lasting legacy would be forged. She was forced to close in 1941 after refusing to make clothes for Nazi wives but reopened after a few months, although she had to temporarily abandon her preferred style that required a lot of fabric and shift to the utilitarian short dresses.

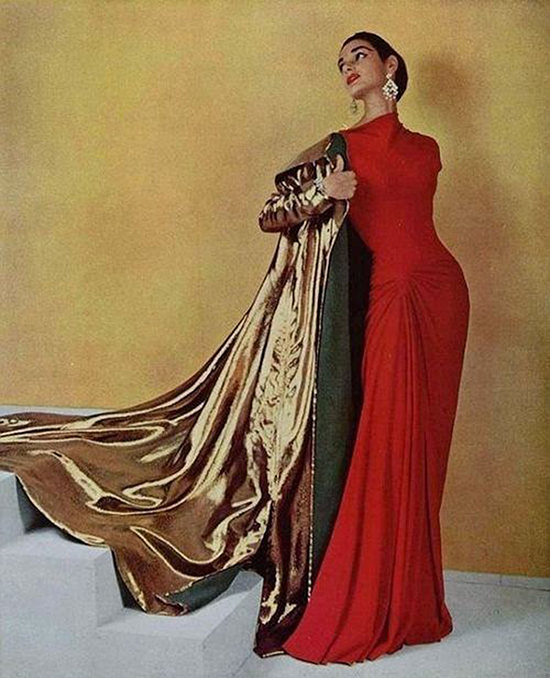

Refusing to admit Germans to her shows, her final wartime collection was a patriotic red, white and blue as an affront to the occupying powers.

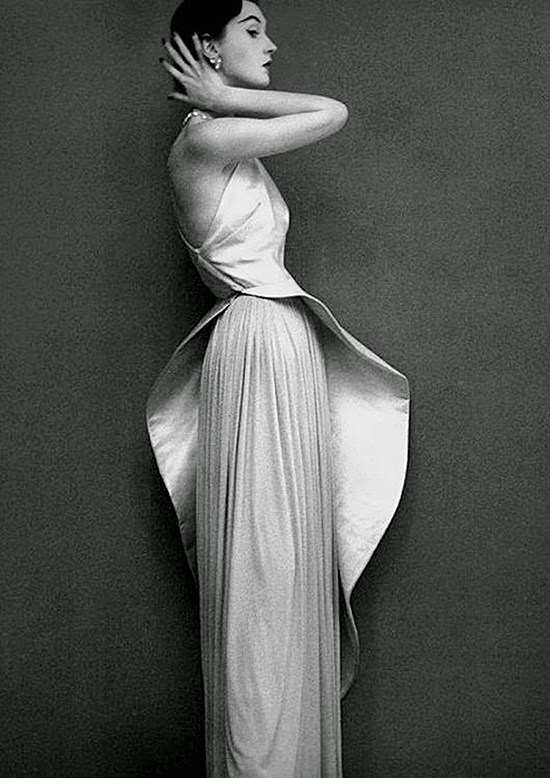

After the war, with more fabric at her disposal, Grès was able to experiment further and perfect her signature draping, this time with tighter pleating done with uncut lengths of double-width silk jersey cut to enhance the female body without restricting movement. It was actually the body that would shape the dress instead of the other way around.

Aside from the fitted bodices, she would have relaxed versions with himation-like draped swags, done with no less technical virtuosity as seen in a 1965 evening dress that has continuous and unbroken panels of fabric incorporating the right fronts and backs.

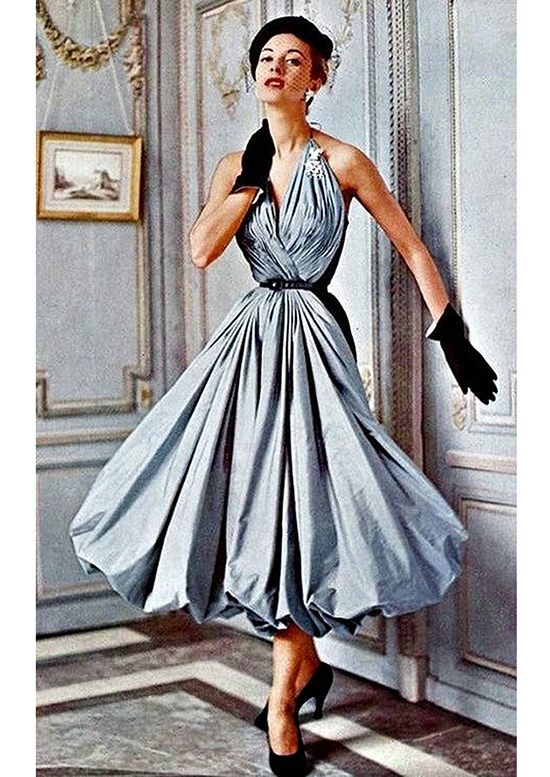

Her genius also lies in her excellent ability to manipulate fabric based on its innate characteristics like when she uses silk taffeta in a 1969 evening dress to create dramatic, voluminous sleeves that contrast with the columnar body.

Her preference for unbroken lengths of fabric, rooted in antiquity when fabric was stitched but not cut into shape, has a more streamlined take in a 1979 red gown utilizing a continuous loop of taffeta that gathers into a one-shouldered pouf, which provides ornament through ingenious cut and draping instead of the commonly done appliqué.

By the ’80s, she had one of the longest-running careers in fashion, having dressed the likes of Greta Garbo, Marlene Dietrich, Grace Kelly, the Duchess of Windsor and Paloma Picasso.

In other works, she would reveal parts of the body with cutouts. She would also experiment with layering geometrically cut pattern pieces to create a free-flowing design like in a FW1972 evening dress. It was works like these that made the New York Times call her couture house “the most intellectual place in Europe to buy clothes.”

Regional costumes from exotic countries like India also fascinated Grès who mixed geometric shapes with traditional forms, creating bifurcated gathered skirts like a man’s dhoti or wrapped just like a sari, but made it asymmetric, a unique trademark, just like in a FW 1980 dinner ensemble in bright purple.

By the ’80s, she had one of the longest-running careers in fashion, having dressed the likes of Greta Garbo, Marlene Dietrich, Grace Kelly, the Duchess of Windsor and Paloma Picasso.

She also received the Legion of Honour aside from so many other awards. Unfortunately, wrong business decisions forced her house to declare bankruptcy, losing the fortune that took her six decades to build, leaving her living in poverty.

Thanks to her friends, Hubert de Givenchy, Yves Saint Laurent and Pierre Cardin, she was able to rent an apartment in Paris and continued sewing garments for her friends.

Later, she moved to the south of France and was placed in a low-income retirement residence by her daughter, Anne. In keeping with her reputation, her death was a mystery. It was held secret from the public by Anne who for 13 months impersonated her mother by phone and by mail.

No one knows what her intentions were but the news was greeted with shock and sadness in the fashion world. She was revered, after all, and inspired so many designers from Balenciaga and Jean-Paul Gaultier to Halston and Issey Miyake.

It was Azzedine Alaïa, however, who is probably Grès’ most lasting legacy since he admired her so much and also did sculptured silhouettes albeit with his own style and techniques.

“She is a woman who counts for so much in the history of fashion,” Alaïa said in reverence for this “Designer of Designers” who remained “The Sphinx of Fashion” till the end.