Designers look up to the clouds

Cloudy images are on the fashion radar this season with pouffed dresses and bubble silhouettes aplenty at the Spring/Summer 2025 runways.

Fashion darling JW Anderson opened his show for Loewe with a billowing white dress with gray florals paired with upside-down aviator glasses while at Comme des Garćons, cumulus clouds were piled on in tiers. At the recent Ternocon, Ezra Santos’s Muslim princesses came out in rose gold metallic clouds and draping that turned into bubble hems, with flocks of birds adorning his pieces that evoked the heavens. Ezra’s mentee, finalist Lexter Badana of Roxas City, was inspired by the Mediterranean blue glass sculptures of Ramon Orlina to fashion resin-infused organza into wispy clouds of butterfly sleeves, panuelos and head gear.

Designers and artists have always been fascinated with the sky. It’s almost like a canvas with the clouds as brush strokes—spreading, curling, swirling, overlapping, changing in color from luminous white against soft blues to menacing grays of impending rain and radiant crimson and purples as the sunsets. Clouds are at once out of reach, impermanent, and overpowering, with a language of their own that is constantly changing, allowing for so many possibilities to which one can project infinite moods, meaning,s and thoughts. It’s no wonder that they have intrigued for centuries and continue to do so today, with #clouds having over 130 million posts.

It wasn’t until the early 19th century that a system of naming clouds was invented by British chemist and meteorologist Luke Howard, inspiring Goethe who was so overwhelmed with the findings and their implications on the worlds of science and art that he wrote a series of poems dedicated to him. Howard’s theories also spurred Romantic painter John Constable to embark on his evocative studies of clouds, depicting their transient nature as metaphors for the impermanence of inner states.

“Clouds for Constable were a source of feeling and perception, an organ of sentiment (heart or lungs) as much as meteorological phenomena,” wrote author Maty Jacobus. “If painting is another name for feeling, and the sky an organ of sentiment, then his cloud sketches are less a notation of weather effects than a series of Romantic lyrics: exhalations and exclamations, meditations and reflections, attached to a specific location and moment in time.”

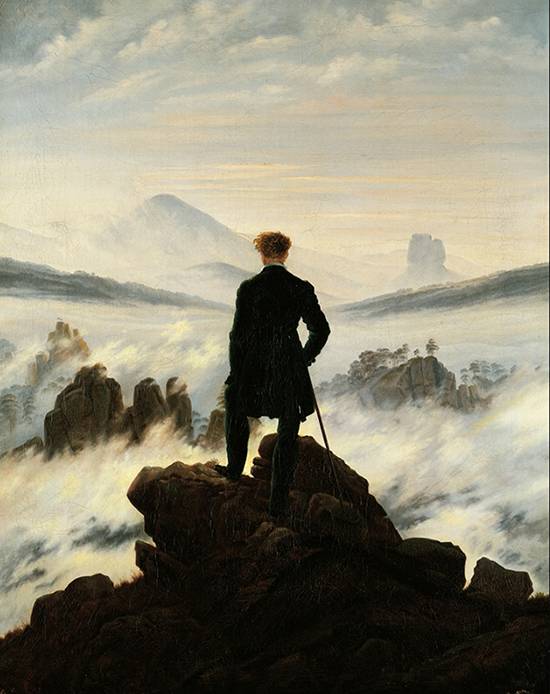

German landscape painter Caspar David Friedrich, however, was one of the artists not drawn to the idea of organizing natural phenomena into categories, finding it a limiting factor in the expressive potential of clouds in art. He nevertheless created the 1818 painting “Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog” which is one of the works that epitomizes Romanticism.

Our own Felix Resurrección Hidalgo, one of the greatest Filipino painters of the late 19th century, painted clouds magnificently in his seascapes that evoke the violence and unpredictability of the ocean. Although considered an Impressionist, some critics have found that some of his works, like “Chateau d’If,” have an affinity to Romantic painter JW Turner.

Hidalgo’s skies are his own, however, exhibiting both luminism and impressionism, the former characterized by attention to detail and the hiding of brushstrokes, whereas the latter lacks detail and emphasizes the brushstrokes. He was first and foremost a classicist—just like Fernando Amorsolo whose brilliant morning skies as well as fiery sunsets were evocative of the beauty of the Philippine countryside—and has stood the test of time.

With intimations of the divine, it is no surprise that there are 125 references to clouds in Scripture, based on the study of author Fleur Dorrell who discovered how “clouds reveal the presence and glory of God.”

Unlike ancient Jewish communities and the early Church, we now have the meteorological expertise to know how clouds are formed, their purpose and how to predict weather quite accurately, “something the ancient civilizations were constantly preoccupied with because they saw the consequences of bad weather every day, so much so that they cultivated a series of deities to appease and worship in the hope of good weather, fertile land and a rich harvest on which their life was so dependent.”

Gazing heavenward, designers, no doubt, have gathered divine inspiration as well. Iris Van Herpen looked towards 17th-century celestial cartography, rich in mythological and astrological symbolism, to create a haute couture collection comprised of undulating, laser-cut silk layers overlapping like contour lines on maps with the fabrics shaped by the human figure to create kinetic sculptures. Some pieces have black outlines that look like stylized clouds from which dark eyes gaze mysteriously. A collab with artist Kim Keever features his watery cloud motifs printed on sheer organza layers overlaid in nebulous multidimensional shapes.

For one of her shows, Sarah Burton got her ideas on the rooftop of the Alexander McQueen studio where the views stretch from St. Paul’s Cathedral to the London Eye, watching the formation and coloration of clouds from daybreak to nightfall to produce silhouettes that fused the structured with puffs of tulle and net and employing prints in a palette of cumulus thunderclouds melting into golden hues and finishing off with a night sky. Going all-out with the theme through a clear dome of bubble forms for the venue, she likened the McQueen woman as a “storm-chaser” who values freedom and a bit of unruliness.

“To relinquish control and be directly in touch with the unpredictable is to be part of nature,” Burton said, “to see and feel it at its most intense, to be at one with a world bigger and more powerful than ourselves.”