Brooching it in 2026

Brooches are big in 2026, as predicted on the runways and on Pinterest. The latter, used by over 500 million people worldwide, has an accuracy rate of 88 percent for the last six years. But you don’t need Pinterest to tell you that, since style setters in showbiz and even business are already seen wearing them: box-office kings Alden Richards and Joshua Garcia at network parties, and SM Supermalls president Steven Tan and eventologist Tim Yap at charity balls, among others.

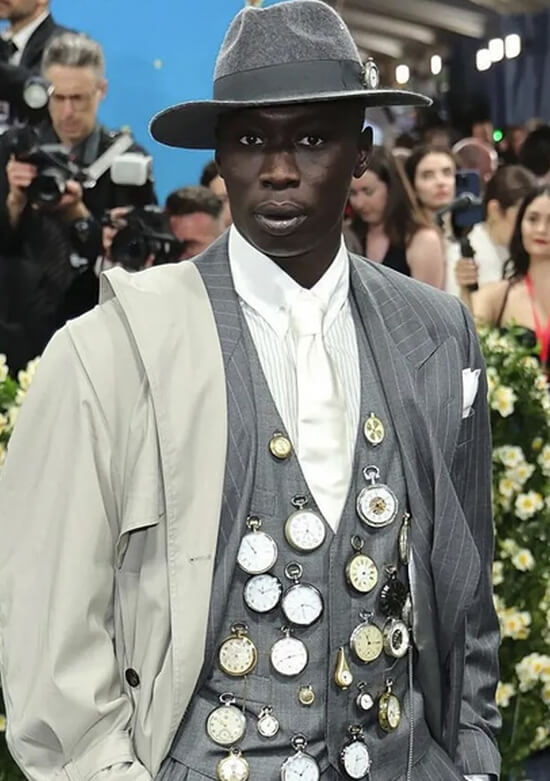

It’s funny that men are in the spotlight now for wearing them, since these jewels have been mostly associated with women in recent fashion history. Men had boutonnieres or lapel pins, which were not as flamboyant, distinguishing them from brooches. But the very fact that men could now actually take pieces to wear from their girlfriend’s or grandma’s jewelry box says a lot about how fashion has become less about gender and more about an expression of individuality.

They were genderless to begin with when they originated in the Bronze Age, called fibulae in continental European contexts as clothes fasteners for men and women, developing into highly decorative variations that were important markers of social status, like the Celtic specimens in enamel and coral inlay from 400 BC and later the elaborate ones in pearls and gemstones during the Byzantine era. Medieval noblemen wore intricate, jeweled pieces as a clear display of wealth and power, and by the Renaissance and Victorian eras, they became virtual works of art used by stylish gentlemen and ladies to signify status and refinement.

Pre-colonial Filipinos had gold and bronze clasps and beaded adornments to fasten the baro, the patadyong, and other traditional garments. Visayan women in the 14th–15th centuries were recorded wearing badu blouses fastened with gansing brooches or cords, alongside other gold jewelry. With Spanish and American colonization, brooches became popular fashion accessories to embellish the traje de mestiza and later the terno, with Baroque, Art Nouveau, and Art Deco styles featuring gemstones, enamel, and other materials alongside precious metals.

Another form of the brooch was the military medal, blending military recognition with jewelry, just like the Philippines’ Jolo Campaign Medal, a historical bronze decoration for Spanish military personnel involved in the 1876 campaign against the Moros and later for WWII involvement in Jolo, recognizing service in the battles for liberation from Japan. In the same spirit, flag pins can be worn by any citizen as a symbol of patriotism, and various pins can signify affiliation with an organization, club, or advocacy.

Brooches also honor the dead, like the Remembrance Poppy worn in British Commonwealth countries and the US to commemorate military personnel lost in war. When Queen Victoria’s husband, Prince Albert, died in 1861, jewelry fashion reflected the monarch’s mourning, turning heavier and more somber in black enamel, jet and black onyx, including mourning brooches with a lock of hair and a portrait of the deceased, worn until the end of the Victorian period. This brooch later developed into keepsakes of loved ones who were living, their hair encased in the brooch or braided and woven into a band to which clasps were affixed.

Before her widowhood, Queen Victoria actually started a tradition of some of the most extravagant brooches that found continuity all the way to Elizabeth II, who had a notable collection of different styles, many with hidden meanings, such as the flower basket brooch that her parents gifted her on the birth of her son, King Charles III, in 1948.

Madeleine Albright, the first woman to serve as US Secretary of State, was also famous for her brooches—so much so that she was the inspiration for Tory Burch’s oversized floral pins in her FW 2025-2026 collection, channeling how her brooches were a form of “diplomatic communication,” using jewelry to convey her stance on various issues. In her memoir, Read My Pins: Stories from a Diplomat’s Jewel Box, Albright coined the term “statement brooch,” which delivers messages—wearing flowers, butterflies and balloons on good days, and opting for beetles or carnivorous animals for difficult negotiations. She deliberately wore a snake brooch to a meeting with Saddam Hussein after she had previously been called a snake in the Iraqi press.

A brooch that was inadvertently perceived as intentional was the Blackamoor one worn by Princess Michael of Kent at a Buckingham Palace Christmas banquet, where Meghan Markle, then fiancée of Prince Harry, was also in attendance. The press and social media labeled her as racist for alluding to Markle’s African-American heritage by wearing the particular piece, which was interpreted as an affront to the prince’s choice of bride.

Although the princess apologized for causing unintended offense, the incident still sparked a lot of controversy, labeling the piece as an exoticization of Africans and one born of slave heritage, even if the moretto jewel, according to jewelers like Codognato and Gioielleria Nardi, is actually a tribute to Middle Eastern traders in Venetian history and is in fact depicted as princely, like Balthazar of the Three Kings (justifying her wearing it for Christmas). Whatever her real intentions were, what is clear is that a brooch isn’t just a brooch, and jewels aren’t just stones and metal, since they carry so much history and convey so much meaning.