How the kimono survived the modern age

KYOTO, Japan—You will never see more people dressed in the kimono than in this city because it’s the heart of traditional Japan and even tourists are garbed in Japan’s national dress to complete the experience as they visit ancient temples, gardens, and cobbled streets that have remained virtually unchanged for centuries.

But, just like our terno, the kimono has evolved through time and has struggled to remain popular despite its playing a dynamic part in the country’s dress history, embodying its cultural values and reflecting the Japanese sense of beauty. The word literally means “thing to wear,” but it did not always have that name.

Its origins can be traced to the Heian period (794-1185 AD) when Japan stopped sending envoys to the Chinese dynastic courts, preventing the importation of goods, including clothing, thus creating a cultural vacuum that facilitated the development of a Japanese culture independent from foreign influence. Previously, during the Kofun period (300 to 538 AD), tribal chiefs and priestess-queens wore clothing similar to those in the Han Dynasty, and this continued through to the Tang Dynasty as immigration between the two countries progressed.

With the flowering of kokofu or “national culture,” new technology transformed wrap-front robes with the “straight-line cut method” that allows the garment to adjust to any body shape. Later, the layering of robes came into fashion, with motifs, symbols, and color combinations reflecting the wearer’s social status, political class, personality traits, and virtues. Only the upper class, for example, could wear the jūni-hitoe of 12 layers in silk using expensive dyes. The innermost layer, called kosode, served as underwear and was eventually worn on its own, predating the modern era’s fashion of using underwear as outerwear.

It would be worn with red hakama trousers during the rise of the samurai class in the Kamakura period (1185-1333), but by the next era of Muromachi, women abandoned the pants, leading to the invention of the decorated obi sash to keep the kosode together.

By the time of Azuchi-Momoyama (1568-1603), Japanese dress became more refined, as artisans unraveled new skills of weaving and decoration, reaching its height during 1600s Edo, a period of unprecedented peace, political stability, economic growth, and urban expansion. Although exclusive styles would at first only be available to the ruling samurai class, it was the merchant class who created fashionable dress, since they benefited most from the growing market for luxury and thus demanded new clothes to express their newfound confidence and affluence.

This new dress would be connected to the “floating world” of pleasure, entertainment, and drama in the 17th to 19th centuries. At Yoshiwara, the pleasure district, which was the hub of popular culture, there would be a parade of the highest-ranking courtesans wearing the latest fashion. Just like the influencers of today, their style, together with those of geishas and kabuki actors, would be copied by ordinary women.

It was during this period when the national dress was a visibly unifying cultural marker. During the rare occasions when one came into contact with foreigners, a Japanese person had a sense of identity since the visitors did not wear the kosode.

The making of the attire was highly regulated, just like with other art forms like painting, poetry, ceramics, and lacquerware, which adhered to certain aesthetics. The most important principle was using the explicit to denote the implicit: the cherry blossom, for example, symbolized mortal feminine beauty so it was on women’s dress, not men’s. Additionally, women would wear the motif for leisure, not work. With the many intricacies of choice in fabric, color, and pattern that would denote gender, age, and rank, it was essential to consult Hinagata Bon books of design.

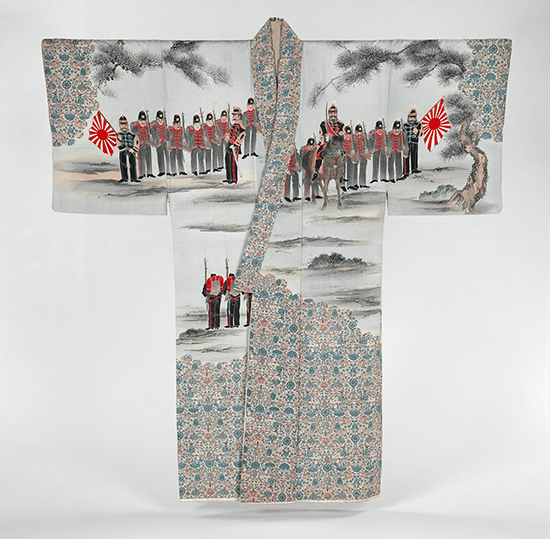

The fashion and arts during Edo would reflect their culture at its purest since the country’s isolationist policy would later give way to the Meiji era’s opening to the West in the mid-19th century, when the word “kimono” first came into use to describe the national dress. With the opening of ports to foreign trade, there was a shift to more Westernized clothing. Trying to move away from the samurai leadership of the past, the government banned kimonos in favor of British styles for the military. Elite women also began to adopt garments from Western societies.

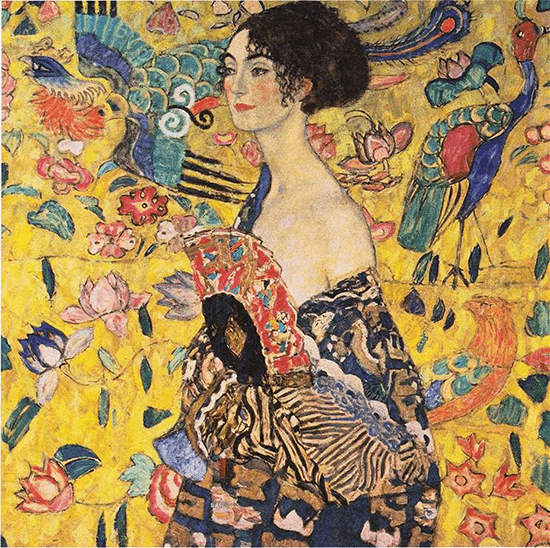

Alternatively, in the early 20th century, the kimono influenced European art and fashion, as Japan started producing “kimonos for foreigners,” which had a sash in lieu of the obi, which was too complicated to tie, and even added extra panels that could be worn as petticoats.

After WWII, as Japanese culture became increasingly Americanized, the government promulgated laws to protect cultural properties like the techniques of weaving and dyeing. Pride in the kimono and its related crafts would usher in a renaissance, with kitsuke schools teaching women how to don kimono the proper way. By the 1970s, kimono retailers developed a monopoly on prices and the perception of kimono knowledge, allowing them to dictate prices and promote expensive purchases of formal kimono, one piece of which, if sold, could support the seller comfortably for three months.

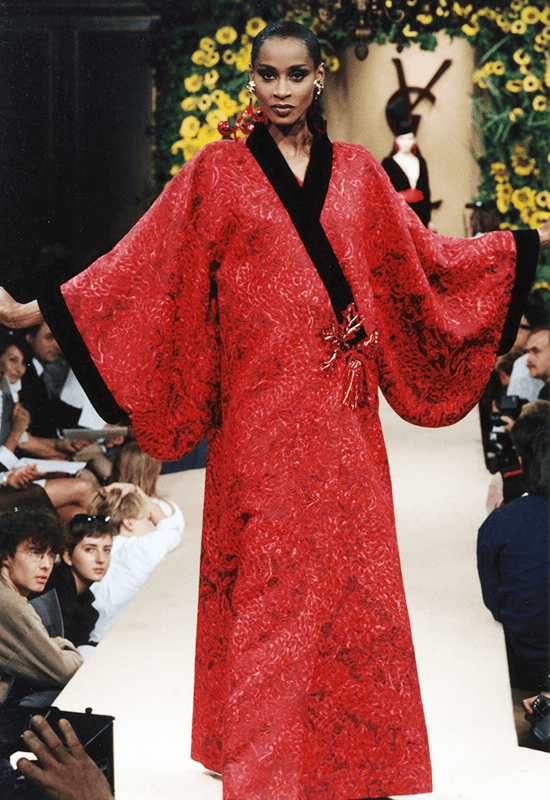

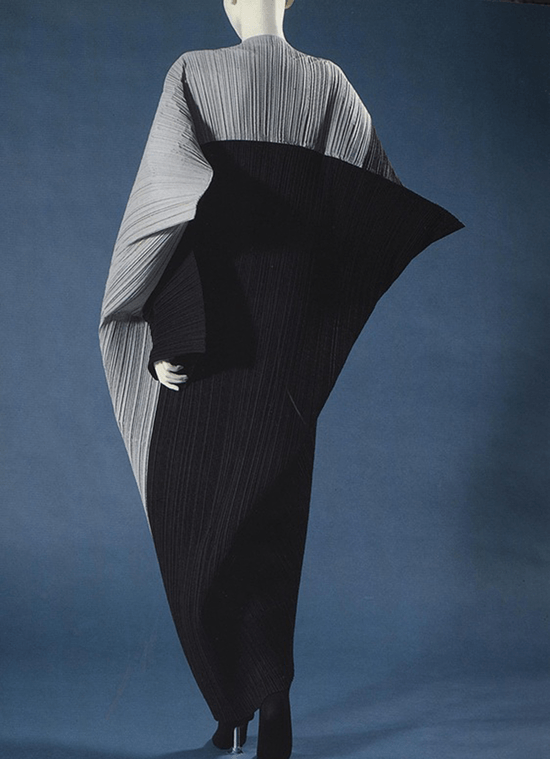

As the economy collapsed in the ’90s, bridal kimono trousseaus were replaced with more affordable western gowns. A renewed interest in Japanese culture, however, occurred worldwide, with designers like Yves Saint Laurent, Alexander McQueen, and John Galliano for Dio, referencing the kimono; and entertainers like Freddie Mercury, Madonna, and Bjork donning Japanese dress. Japanese designers like Rei Kawakubo, Yohji Yamamoto, and Issey Miyake would also take inspiration from their traditional attire.

In Kyoto today, ateliers like SouSou are reinterpreting the kimono for the 21st century. Founder Takeshi Wakabayashi related how he “decided to create a line that comes out of our culture, that people wanted to buy because they look good, are comfortable to wear and priced reasonably. It is not tradition just for the sake of tradition.”