Luisa Casati: A living work of art

If Luisa Casati did not exist, designers and artists would have to invent her, but would probably still fall short of what she strived to create of herself as “a work of art,” living her life as a rebellion against the mundane.

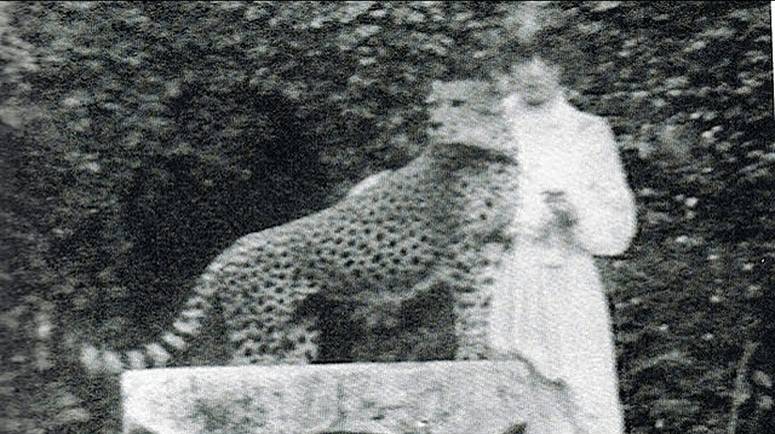

Whereas celebrities today garb themselves in leopard-skin prints, the Italian heiress and art patroness pranced around naked but for a fur cloak, with pet cheetahs on diamond leashes, live snakes round her neck, and a torch-bearing blackamoor lighting her way.

To make an entrance at a party, she wore a couture dress of light bulbs that electrocuted her into a backward somersault. She was, no doubt, the most scandalous woman of her day, astounding the most jaded members of the international aristocracy.

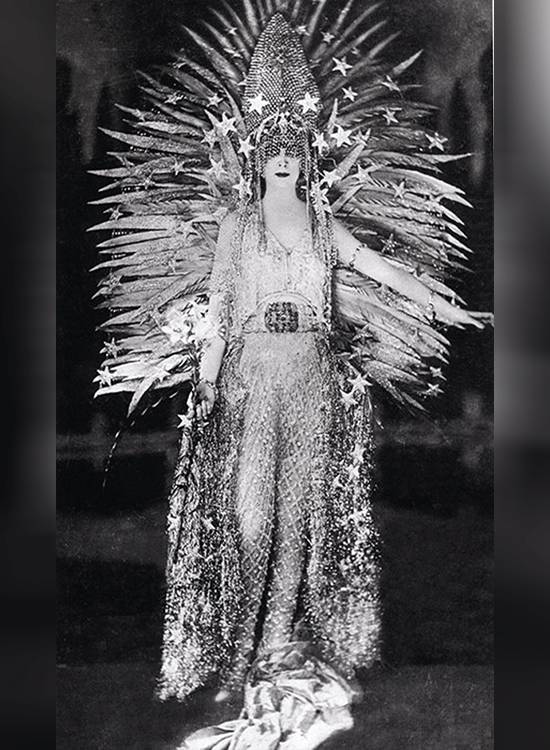

Even Pablo Picasso, the disruptor himself, could not erase his memory of the Marchesa after attending a dinner party that she hosted in Rome in 1917. He could still recall the footmen in their 18th-century livery throwing copper filings into the fireplace to turn the flames a brilliant green, the massive boa constrictor that formed a coiled pattern on a polar bear skin rug and a flock of albino blackbirds dyed in different colors. There were also mechanical birds in gilded cages and white peacocks perched on every window. The peacock feathers would later be used to create an elaborate costume, using fresh chicken blood as accessory.

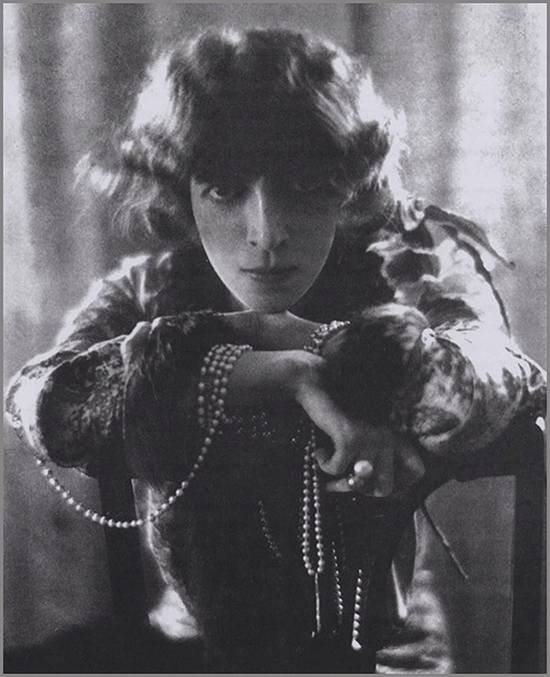

The pièce de résistance was the arresting appearance of Luisa herself “in a pearl-embroidered gown with a stiff Elizabethan ruff collar and a neckline that plunged to her navel.” Standing at six feet tall and incredibly skinny from a diet of gin and opium, she powdered her skin cadaverous white, dyed her hair flaming orange, painted her lips vermillion, used belladonna (known as deadly nightshade) to enlarge her pupils, and exaggerated her green eyes further with black velvet—appliqued lids, poisonous atropine for glitter, and immense false eyelashes. On her finger, a portable incense holder emitted clouds of perfume.

A party with her servants covered in gold fueled rumors of their death from the toxicity of the paint used. Guests struggled to identify the real Luisa, who commissioned wax effigies of herself with identical outfits and sporting her own hair, seated at the candlelit dinner table.

The wax dummies started another rumor that she kept cremated remains of her former lovers inside them, a story similar to the one attributed to Cristina Trivulzio, the Italian princess of Belgiojoso.

, 1935

Cristina, a heroine of the teenage Luisa, was notorious for the odd rites that she performed to mourn dead lovers. The two heiresses were uncannily similar—both introverted children who inherited a fortune and could not quite fit into society because of their eccentricity. Luisa felt such a strong connection that she attempted to contact the princess in séances, and named her own daughter Cristina.

Born in Milan in 1881 to textile magnates Alberto Amman, who was made a count by King Umberto I, and Lucia Bressi, Luisa had an affluent but dysfunctional family life. Her mother died when she was 13, and her father died two years later, making Luisa and her older sister Francesca reportedly the wealthiest women in Italy.

The early loss of her parents propelled a drive to make an indelible mark on the world. Marrying Camillo, Marchese Casati Stampa di Soncino at age 19, she was able to leverage her title, wealth, and influence. It was an affair with the poet Gabriele d’ Annunzio, however, that would spark her transformation into a femme fatale and muse to the avant-garde.

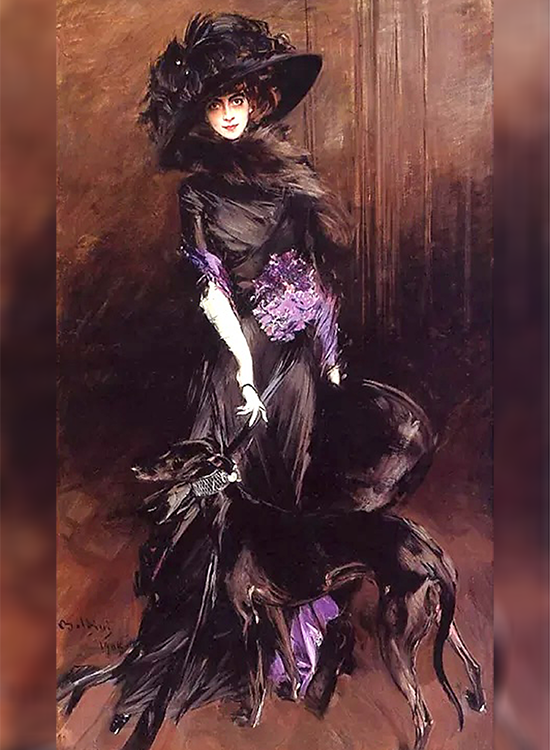

In Venice, d’Annnunzio introduced Luisa to Giovanni Boldini, who painted her portrait with a greyhound in 1908, displayed at the Paris Salon where it created a buzz among the cognoscenti.

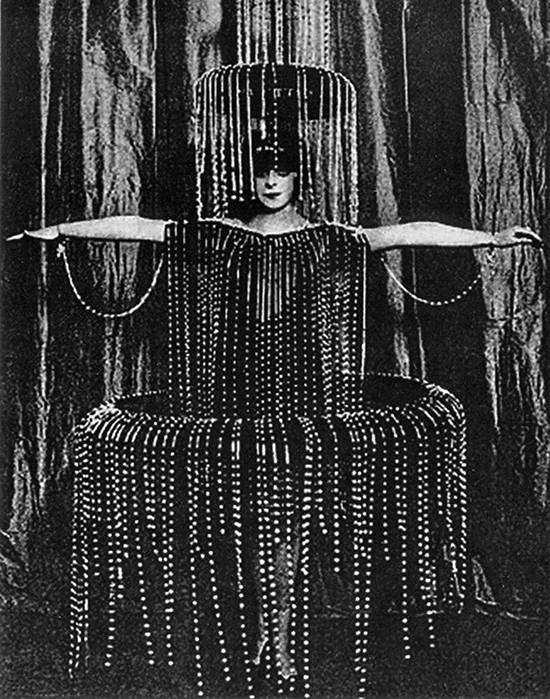

Hanging with artists, Luisa consolidated the independence from her husband by acquiring the Palazzo Venier dei Leoni on the Grand Canal as her residence in Venice, assembling a household staff of black manservants, trusted gondoliers with white gondolas (when the law required all gondolas to be black), enclosing herself with a menagerie of exotic animals and strolling in the moonlight of Piazza San Marco wearing nothing but a fur coat and pearls. Although Fortuny was a preferred designer, she grew tired of his creations which noblewomen began to favor, shifting to Leon Bakst of the Ballet Russes to design a more flamboyant wardrobe—perfect for hosting the magnificent parties and masquerades that she would be known for.

Moving between Venice, Rome and Paris, she was christened “The Medusa of the Grand Hotels” because of her staying in luxury hotel suites which she furnished with animal skins, mechanical songbirds, feathers and magical trinkets. In her quest to become a living work of art, she promoted artists who immortalized her in their works. By 1920, she settled for a long period in Capri, a shelter for artists and homosexuals, but tired of it eventually and wandered through Europe. During this time, her style became more bizarre—walking along Rue dela Paix in a black velvet Vionnet dress, a tiger-skin top hat and a pirate eye patch. Her wigs were in vivid colors and one was made with stuffed snakes. One time she dressed as Lady Macbeth with a wax replica of a blood-stained hand on her throat.

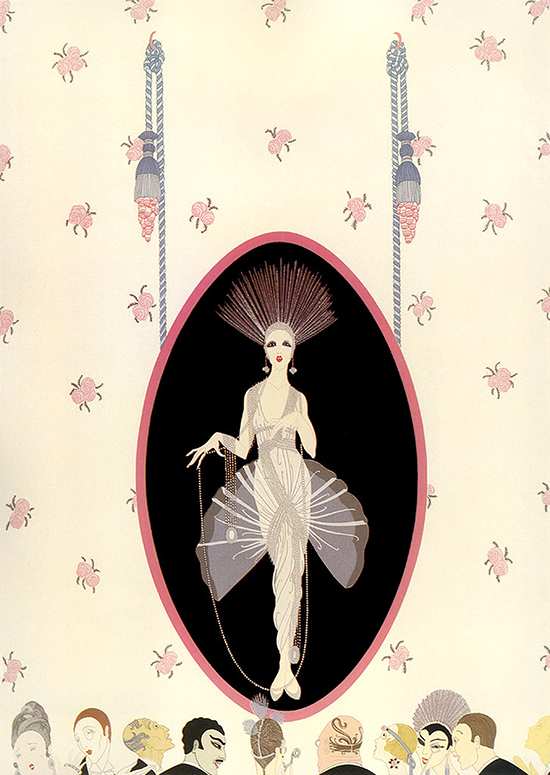

She eventually bought a house in Paris, hosting more lavish parties while appearing at the most exclusive ones like the 1924 Bal du Grand Prix for which she commissioned Erté to design her costume. The Russian artist later said, “The Marchesa was, in fact, a shy person. Her eccentric behavior was a cover for her shyness.”

Around this time, her accountants started warning her about immoderate spending but she still threw a grand masquerade ball which ended with a catastrophic storm that frightened guests as the lights went out. In 1931, she celebrated her 50th birthday having insurmountable debt, managing daily purchases by selling off jewelry until the courts arranged for the public auction of her house and its treasures. She moved to London where she could count on her daughter, who became Lady Hastings, as well as some old friends but by the 1940s she had to keep moving, changing address 15 times.

Destitute as she had become, she still kept up appearances, creating dresses from thrown-away monkey fur and using shoe polish as kohl, “creating nobility out of poverty,” said Cecil Beaton. She made collages out of clippings but the minute her friends encouraged her to mount them in an exhibit to raise cash, she abandoned the project. “The Marchesa seemed to have a genuine horror of money,” observed art historian Philippe Jullian.

Luisa died in 1957 at the age of 76. She was laid out in her favorite black and leopard dress with one of her stuffed Pekingese at her feet. Her granddaughter Moorea Black left an epitaph on her tombstone from Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra: “Age cannot wither her, nor custom stale her infinite variety.”

The Marchesa continued to inspire beyond her death. Jack Kerouac dedicated poems to her, Vivien Leigh and Ingrid Bergman played characters based on her, and designers like John Galliano, Alexander McQueen, and Karl Lagerfeld channeled her in their collections. She lives on in galleries around the world, where her image—hailed as possibly the most artistically represented woman in history after the Virgin Mary and Cleopatra—is seen in portraits, sculptures, and photographs.