Take a bow!

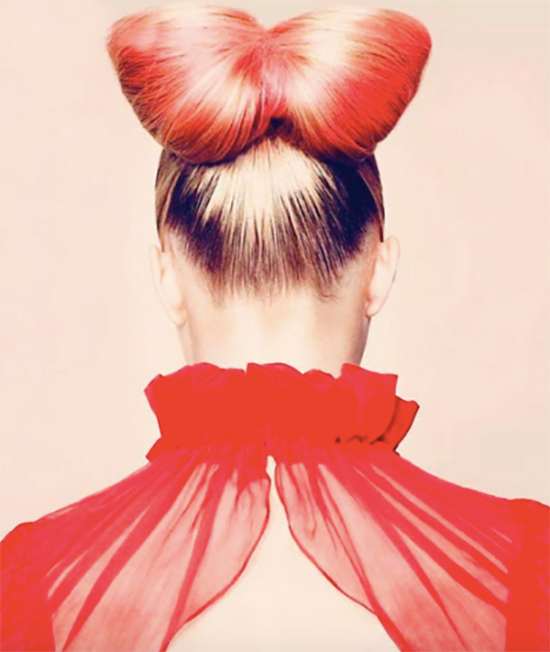

The bow may have started as a necessity — as a way to tie things and keep something in place, both on objects and garments, and even on the body as it is used to keep hair together — but trust man to turn the quotidian into a work of beauty, imbued with artistry.

At the Metropolitan Museum of Art, one can find a set of Sumerian hair ribbons made of gold from 2600 to 2500 BC. Even earlier in 6000 BC, there were warp-faced weave bands excavated from Çatalhöyük in Turkey.

Adding precious care to ornamentation has made the bow indispensable to human civilization. A present no doubt becomes an offering of joy because of the flourish of a sumptuous ribbon. The felicity it brings extends to garments as well as to fashion accessories.

Diana Vreeland once said, reflecting the festive mood of the holiday season, “This year, why don’t you consider trimming yourself with ribbons, too?”

Bows, as we know them today, came around the Middle Ages, with the introduction of the woven ribbon, made possible with the invention of the horizontal loom, and were actually worn by both men and women — pinned to clothing and incorporated in hairstyles.

Renaissance paintings like those of Filippo Lippi’s feature angels with ribbons emanating from their garments as they hover in celestial space. A dainty crown of bows appears in Lorenzo Lotti’s “Portrait of a Woman Inspired by Lucretia.”

In the late 16th and early 17th centuries, bow hair ornaments were worn by men as the lovelock, a long strand of hair tied together, signifying the wearer’s romantic devotion to his beloved since it drew emphasis to the heart by being draped over the chest.

Louis XIV, aside from wearing bows on wigs, encouraged ribbons as essential to fashionable dress. Courtiers attached them to hats, sword handles, shoes, sleeves, and around the knees.

Yards of ribbon loops on the lower bodice emphasized the wearer’s masculinity. The Marquis de Louvois and the Marquis de Villeroi would supposedly even shut themselves in a chamber for days just to discuss the placement of a bow on a suit.

Women, on the other hand, had the echelle stomacher trims — horizontal rows of large bows down the front — to close the front of the dress and also used them to decorate the elbows and the neck. They would place a bow at the top of the bodice, which had a low décolletage — a trend called parfait contentement or “perfect contentment.”

With no functional purpose, it was a status symbol. This look of Marie Antoinette seems to resonate with the current generation as the cottagecore, royalcore, and lovecore aesthetics have taken over TikTok.

Designers, in turn, have taken their cue, as seen in the SS 2022 collections of Comme des Garçons, Giambattista Valli and Moschino. The madness for bows continues till FW2022 with bows in dresses, shirts, sweaters, and jumpsuits: Sweetness was made monastically austere as Pierre Cardin’s flat bows reemerged at Jil Sander.

Pierpaolo Piccioli reimagined vintage Valentino in a piece comprised mostly of ribbons. Graphic bows came trompe l’oeil at Schiaparelli, Oscar de la Renta and Carolina Herrera.

The bow has indeed gone a long way, from just being an aesthetically pleasing ornament and royal and status symbol to a political and fashion statement.

Designers’ subverting of the saccharine sweetness of the bow has its roots in history. They were used as marks of resistance, after all — worn as ribbon cockades during the French revolution and on hats as a sign of defiance against Adolf Hitler during World War II. French women would scrounge for ribbons and scrap fabrics to adorn their hats and turbans to thumb their noses at the German rules against extravagance.

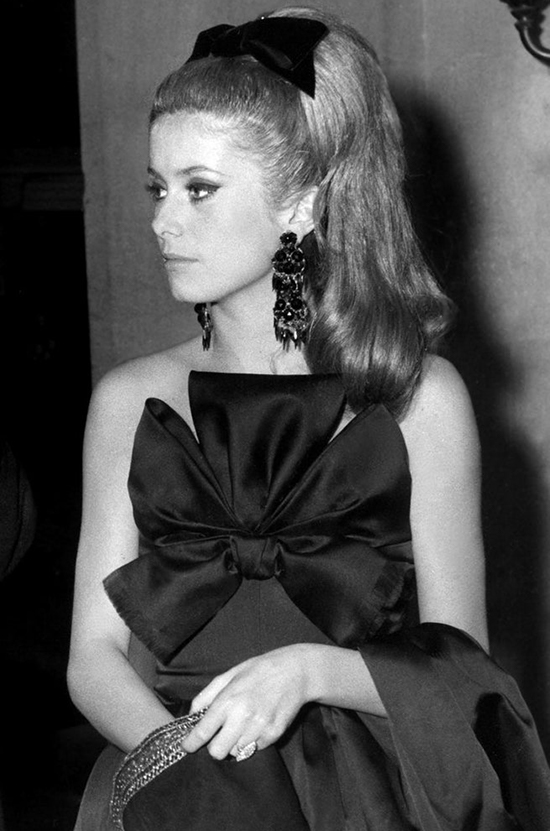

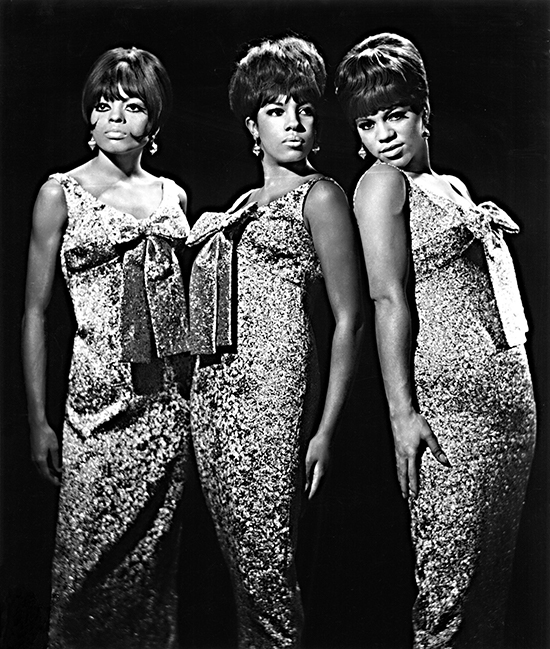

With Christian Dior’s revolution in fashion, the bow also veered away from sweetness to become more sculptural. By the 1960s, French ingenues Catherine Deneuve and Brigitte Bardot made it more coquettish and beatnik styled with winged eyeliner and miniskirts.

As professional work opportunities developed for women from the ’60s to the ’70s, it became a symbol of women’s workplace empowerment through the pussy-bow blouse, appearing on the runways of Yves Saint Laurent and Halston. A mix of the masculine and the feminine, it evolved into a power-dressing staple synonymous with strength.

Margaret Thatcher, the Iron Lady, wore it through much of the ’80s. It was during this period that wearing a bold bow was a way to stand out from the crowd, with Madonna and Princess Diana showcasing it in many of their outfits.

Another form of standing out was using the ribbon to signify one’s beliefs and advocacies. In 1986, the yellow ribbon became a symbol of Ninoy Aquino’s legacy of heroism and martyrdom, rallying the Filipino people to the leadership of his widow, Corazon Aquino, who led protests to topple the Marcos dictatorship and restore democracy in the country.

In 1990, the art activism group Visual AIDS used a loop of red ribbon as an international symbol of AIDS awareness. With the ongoing invasion of Ukraine, the wearing of ribbons in the blue and yellow colors of the beleaguered country’s flag signifies support for its people against Russia.

The bow has indeed gone a long way, from just being an aesthetically pleasing ornament and royal status symbol to a political and fashion statement. Whatever its meaning may be, it’s all about using it in dressing for oneself and harnessing its power to express one’s individuality.