How the ‘immoral’ ballerina turned into a style muse

There’s been a lot of ballet in fashion lately and it’s not just the tulle skirts and corseted bodices of the stage but even the leotards, wraparound skirts, cardigans, and leg warmers of the rehearsal hall. The runways can’t seem to get enough of the ballerina in their collections and “balletcore” has become Gen-Z’s way of adopting the look.

The ballerina, however, was not always one to be emulated. In Edgar Degas’ 1879 painting L’Etoile, a dancer is in the spotlight enjoying her star moment on stage, but in the wings lurks a figure in a black tuxedo—one of the infamous abonnés, or subscribers who were so powerful that when Charles Garnier designed his Paris opera house in the 1860s, he included a special, separate entrance for them so they could have direct access to the girls, whom they preyed on for sexual favors. These dancers, derisively called petits rats, were from impoverished backgrounds and had to give in to the lechers, who would act as patrons to help them advance in their careers. A ballerina, therefore, was seen as immoral and even if one did not succumb to prostitution, she would have been suspected to have done so, anyway.

What has had an enduring impact on female fashion, surprisingly, was performed almost exclusively by male aristocrats. Tracing its origins to the Italian Renaissance, ballet was developed as court entertainment, which moved to France when Catherine de Médici married Henry II. Ballet de cour reached its apotheosis under Louis XIV, who performed many of the roles himself, one of which—from Le Ballet de la Nuit (1653) —earned him the title Sun King because the event ran from sunset to sunrise.

By 1681, Mlle. La Fontaine became the first principal female dancer, and as ballet became more professional and popular in the 18th and early 19th centuries, more women began to enter the field.

During this period, costumes would mirror contemporary fashions but were adapted to allow freedom of movement and to be able to see the footwork, so shorter hemlines and lighter fabrics were used to emphasize the form of the body. This, of course, only reinforced the notion that no respectable woman should appear on stage.

Ballet was only elevated to a respectable art form in the 1830s and ’40s because of the celebrated dancer Marie Taglioni, who had many female fans due to her talent and ladylike image, which was epitomized by her costume in La Sylphide—a white, fitted bodice with a calf-length tulle skirt that would become the archetypical ballerina costume from then on. The respectability was short-lived, however, with the skirt that she popularized being called a tutu, which was derived from the slang word cucu, or bottom—that part of the dancer’s anatomy that patrons would ogle.

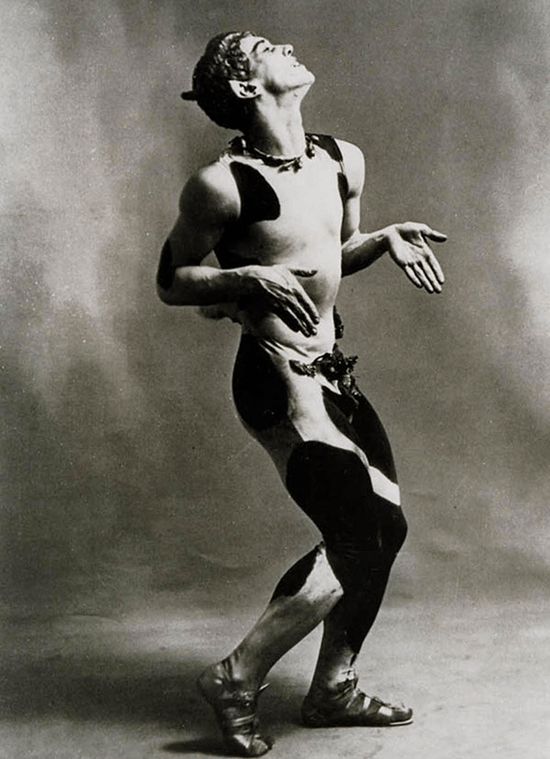

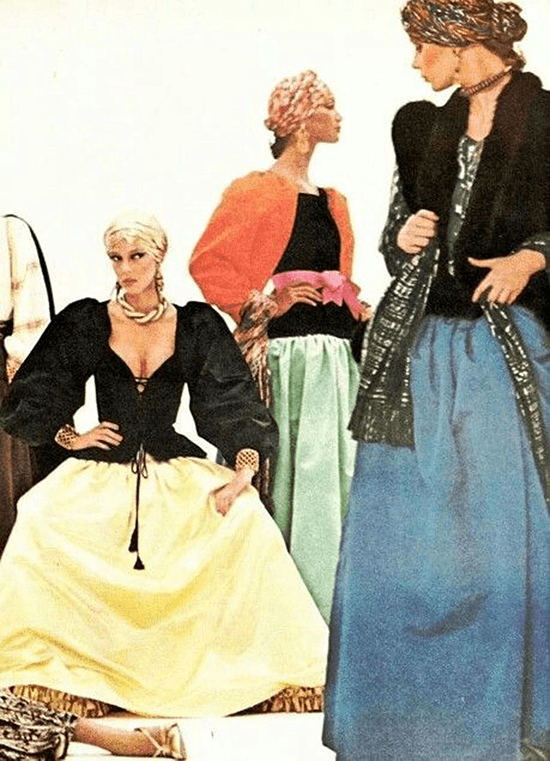

The transformation of ballet into a revered art form beloved by fashion designers would begin with the arrival of Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballet Russes in 1909, inspiring couturiers like Paul Poiret, who channeled its Orientalist aesthetic in harem pants and layered pagoda skirts in jewel colors. These would be referenced over half a century later in 1976 by Yves Saint Laurent for his couture collection and over a century later in 2015 by Rick Owens, who employed the erotic overtones of The Rite of Spring danced by Nijinsky.

Diaghilev’s restaging of Sleeping Beauty (1921) would awaken designers again to the aesthetics of ballet. By the mid-’20s, even when sheaths and tunics were a la mode, Jeanne Lanvin was creating romantic, full-skirted dresses and the modernist Madeleine Vionnet named one of her 1924 pieces Ballerina.

By 1932, Vogue devoted eight pages to the Ballet Russes de Monte Carlo’s production of Cotillon, featuring the costumes designed by Christian Bérard. Bérard’s star-adorned costumes would be an inspiration for a sequin-embellished gown done by his friend Coco Chanel years later. He was also the mentor of Christian Dior, who would have a lifelong association with ballet, starting with his 1947 New Look of fitted bodice and voluminous skirt.

Elsa Schiaparelli would popularize the Sleeping Blue color from the ballet’s bluebird variation and lilac, a color associated with mourning, would lose that connotation because of the “lilac fairy” character.

Just as ballet influenced fashion, the reverse is also true, as ballerinas would wear high-fashion pieces outside the stage, helping to elevate their craft as an art form and profession. Margot Fonteyn, for example, was attracted to Dior’s evocations of the 19th-century romantic ideal that suited her elegant body and posture and would become a lifelong client.

The cross-pollination from ballet to couture and back again could not be better illustrated than in Margot Fonteyn’s 1946 Sleeping Beauty costume, which inspired Balenciaga’s 1950 evening dress for Hattie Carnegie, which in turn was referenced by Mark Happel for the 2012 Symphony in C costume for the New York City Ballet.

In the mid-20th century, opulence and narrative would give way to the abstract athleticism of George Balanchine’s choreography and the corresponding minimalist costumes and leotards that Calvin Klein and Donna Karan would make viable as everyday wear in the ’70s and ’80s. It was also more in keeping with the new generation of women fighting for equality who did not see the classical ballerina as the ideal archetype.

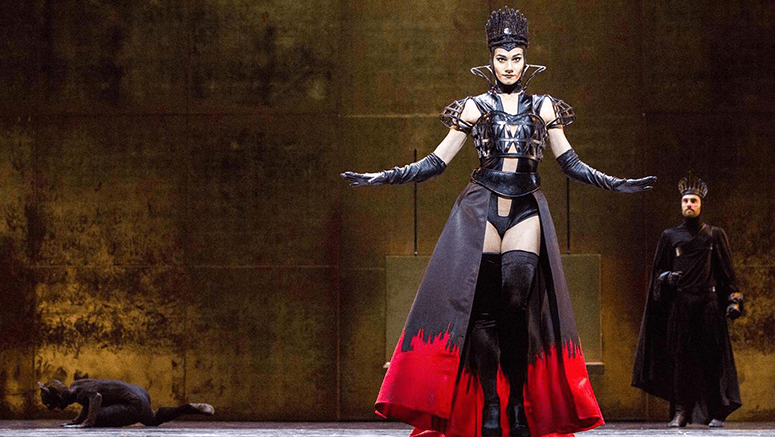

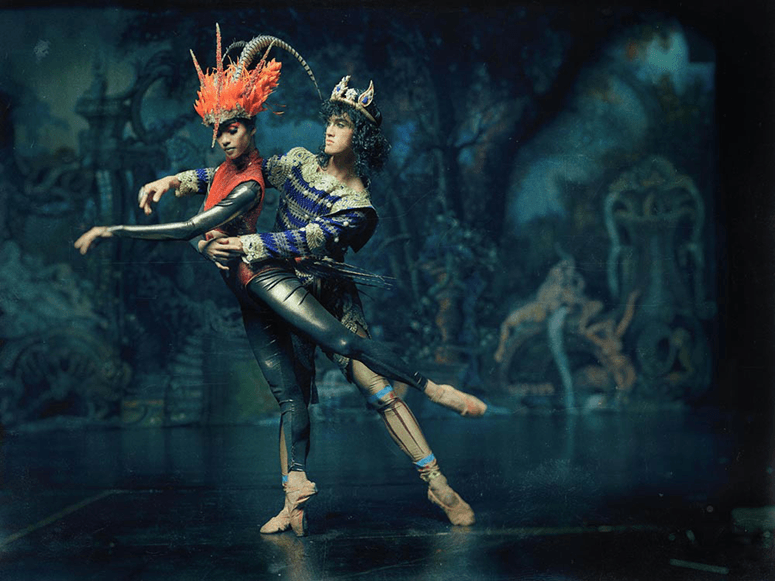

Fashion designers did not lose interest, however, and instead turned to costume design for the ballet, a task that is considered a rite of passage to this day. Mark Lewis Higgins, director of Slim’s Fashion School, designed the costumes of Firebird for Ballet Philippines, reflecting the rich, multicultural aesthetic of his paintings.

Ballet has also entered fashion again now that women are no longer conflicted about expressing romance or femininity in what they wear and can even feel empowered with tulle or chiffon.

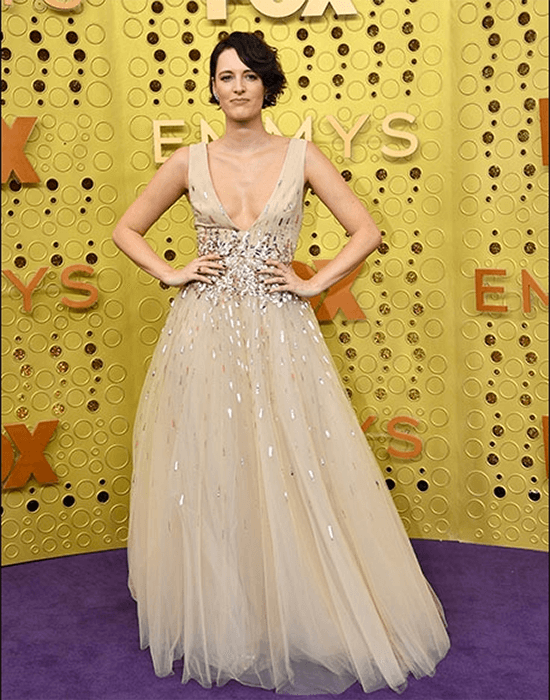

Phoebe Waller-Bridge, the creator of the TV series Killing Eve, chose to dress her murderess, anti-heroine Villanelle, in a pink organza gown by Molly Goddard, who is known for her “bad ballerina” looks. Phoebe received her Emmy awards wearing Filipina designer Monique Lhuillier’s embellished gown made from yards of tulle, made edgy with a daring décolletage.

The dance world continues to bring endless inspiration to fashion and vice versa, as designers conjure as well as subvert the romantic iterations of the ballerina, which keeps evolving both on stage and in streetwear today.