Chronicling a passionate journey into the world of Philippine heritage jewelry

The sumptuously produced publication Alahas: Philippine Heritage Jewelry has much to offer the amateur jewelry buff like myself. As a teenager, I toyed half-seriously with the thought of becoming a jewelry designer “when I grew up.” This probably stemmed from having jeweler relatives, the Velayos, who had established several jewelry shops in Manila.

In addition, and slightly unusually, my businessman father (middle name Velayo) had quite an enthusiastic eye for jewelry and loved to pick out presents for my mother. I didn’t become a jewelry designer, but my love for it, especially Philippine vintage pieces, has remained with me.

Angelica “Gigi” Santos Bermejo’s book is a veritable handbook for Philippine jewelry enthusiasts. Four centuries of Philippine heritage jewelry are covered, from the pre-colonial era to the mid-20th century. It is also notable for the fact that it contains a foreword by historian Ambeth Ocampo, and the end papers include a bibliography, text notes, a glossary of Philippine jewelry terms, and a pictorial catalogue with details of many of the jewelry pieces photographed for the book.

The volume itself is beautifully designed and produced by the author’s daughter and son-in-law, who happen to be multimedia design professionals.

The roots of Gigi’s passion for heritage jewelry were set down when she met Lourdes Dellota in Iloilo during the early years of her marriage in the 1980s. “Tita Uding,” as she was known, introduced Gigi to pre-colonial beads, whose rich history enchanted her and set her off on a journey that has culminated four decades later, with this opus.

Far from being a dry, academic tome, the book is an engaging journey through the pantheon of Philippine jewelry genres expressed in Gigi’s highly personal style. Each chapter begins with a fictional narrative that sets the scene for the archetypes of the heritage jewelry discussed. In the chapter on Northern Luzon jewelry, for example, an imagined Cordillera couple go about their everyday chores while preparing the traditional clothing and accessories needed for the ritual wedding they are about to attend in their community.

After the fictional narrative comes a short historical essay that places the jewelry of the period in context of the times. The author often centers on an emblematic female historical figure of the era, weaving a feminist thread throughout. Sprinkled through the texts are Gigi’s own personal ruminations on her design journey, creating a unique blend of historical fact and personal reflection.

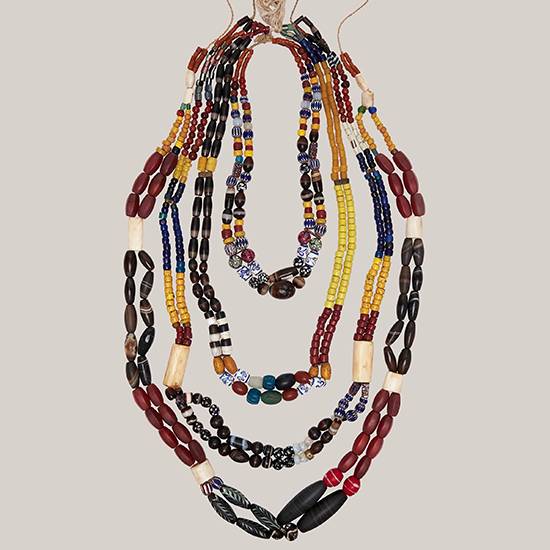

Following the introductory essays are resplendent photographs of the jewelry; some in their natural state as raw material, others combined into Gigi’s inventive creations—fusing heritage and modernity with skill and an appreciation of their historical significance and value.

One learns about the different jewelry elements that mark each period or area. In the Spanish colonial period (1565 to 1898), gold bead shapes are described by their representational forms in nature: florecitas, granada, piña, or balimbing, which gives insight into the sources for their design inspiration.

Types of jewelry of this period are the tamborin necklace with relicario pendants, the simpler señorita necklaces, paynetas (tortoiseshell hair combs embellished with pearls and repoussé designs in both silver and gold), and criolla (half-moon-shape earrings). Reference is often made to period, archaic techniques such as the kalawanging ginto finish, a reddish patina that is applied to gold, and alfajor—a flat-link chain, which is technically difficult to make.

I found most fascinating the beads valued by the Cordillera people in their material culture, spanning centuries; the most well-known one being the lingling-o, similar in shape to two C’s facing each other, and often rendered in metals such as gold and brass. The lingling-o is found in Taiwanese and other cultures. Also considered quite valuable in the Cordillera is the unusual pang-ao glass bead with an inlay of gold foil, which is representative of this region.

Trade beads such as the paraggi, or African trade glass beads with chevron designs, and the blue and white beads called binukkawan or “Ming” (probably due to their similarity to the colors of Chinese blue and white ceramics), are thought to ultimately originate from Venice. Passed around world trade routes, they somehow made their way to the Philippines and many other Asian shores, a mind-boggling thought.

In more modern eras, one discovers the beauty of the diamanté, considered lucky, and its popular shapes and cuts such as the rose-cut or rough-cut. After the war, in the 1950s, there was a fashion for platinum and Palladian metals as the white-gold look was popular; as was pearl jewelry, and the use of colorful gemstones in matching or terno sets.

In her designs, Gigi tends to be bold, almost maximalist, and experimental in that she combines different elements, sometimes from overlapping historical or stylistic periods, as when she blends deep blue chevron beads of the Cordillera with gold florecitas beads and a tamborin relicario from the Spanish colonial period.

The final chapter of the book, “Mata-Mata,” is an ode to the Filipina who loves jewelry. It features an impressive, stunningly designed collection of bold, modern gold jewelry using traditional techniques such as hammering and pulling, all produced to the original designs of her daughter Kara Bermejo, a multimedia designer.

Alahas is a visual feast of a catalogue and a comprehensive, highly personal narrative of the author’s journey collecting and designing Philippine heritage jewelry. It will inevitably claim its place as an engaging, passionate documentation of, and welcome contribution to, the world of Philippine heritage jewelry.