Almost forgotten: Designer Ann Lowe

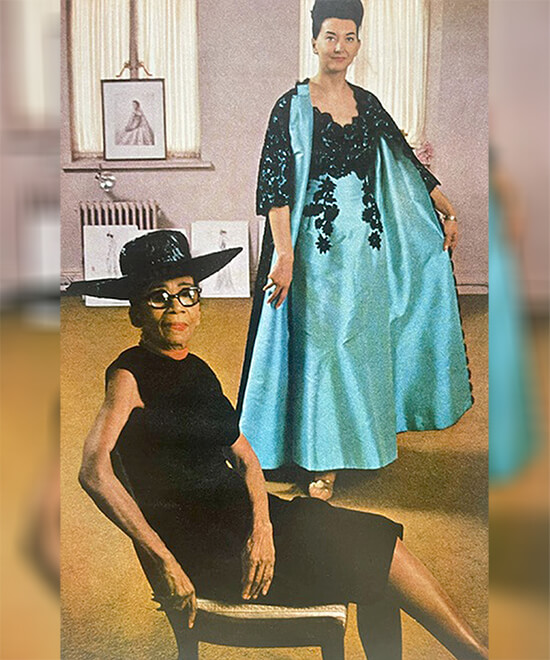

“Society’s Best Kept Secret” is an apt way to describe African-American designer Ann Lowe (1898-1981), who is currently being brought out of anonymity through a number of exhibits and the book Anne Lowe: American Couturier (Rizzoli/Electa) in the US.

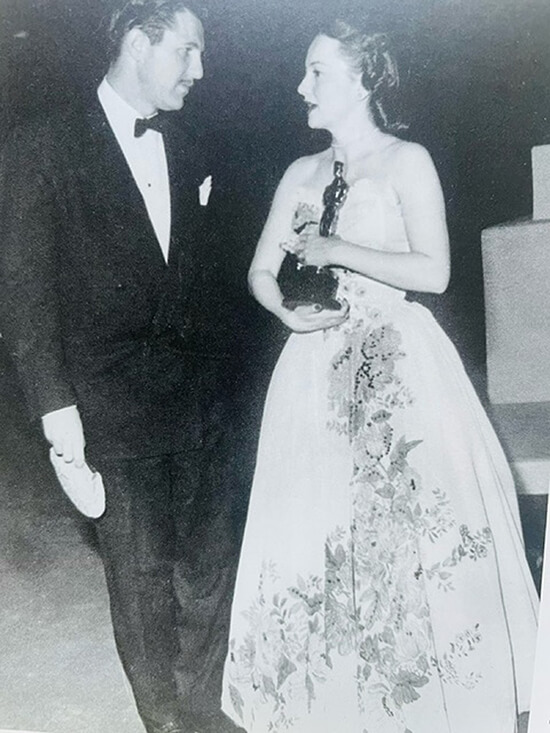

Ann Lowe is best noted as the designer of Jacqueline Kennedy’s wedding dress (not to mention her debutante outfit as well), the gown Olivia de Havilland wore when she won Best Actress at the Oscars in 1947, plus countless other designs worn by America’s Social Register.

Her creations were featured in the Sixties in publications like Vogue, Town and Country, and Vanity Fair. She has 10 gowns in the permanent collection of New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art and others at the Museum of New York, FIT’s Costume Museum and the Smithsonian Institute. She designed for Saks Fifth Avenue, I. Magnin, Neiman Marcus, and other prestigious stores. How could she go unnamed and unnoticed? But that is exactly what happened to her.

To study Ann Lowe’s life and examine her haute couture creations is to have an example of how dreams can be fashioned from the most difficult of materials; in her case, a barely rudimentary elementary education, two failed marriages and that perpetual, major stumbling block that is racism.

Yet she created, with an eye on French couture, princess-worthy gowns for the fairytale moments in the lives of socially prominent women. Outside of that rarefied circle, which included the Bouviers, she was unheard of. She continued to remain anonymous even while trying to be recognized, at least for the Kennedy wedding gown.

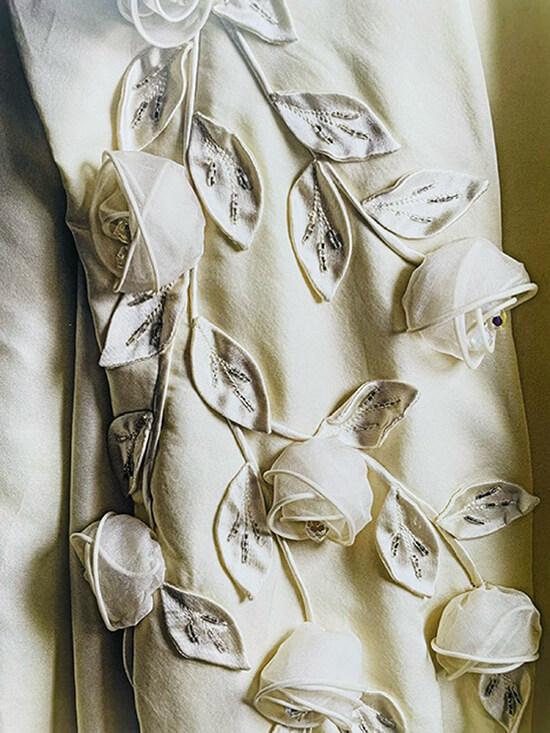

I had a chance to see Ann Lowe’s work up close at the Met’s “Women Dressing Women” exhibit earlier this year. The single stunning piece chosen from among many in the Met’s permanent collection was a 1960s off-white cotton organdy gown, sleeveless and cut at the empire according to the prevailing fashion. Its striking detail is a garden blooming on the skirt of pink silk organza and green silk taffeta carnations. Hand-formed flowers were a signature of her style. It made me think of my lola Marina Antonio, who created her own floral embellishments, too.

I couldn’t help but compare Ann Lowe’s obscurity in the fashion world to Marina Antonio, as both were well known within the register of society they created for, yet were unknown outside those circles for different reasons. Both Ann Lowe and my late grandmother were content and fulfilled mainly by creating marvelous gowns, and fame was not a goal.

I must say that Ann Lowe had the much more difficult time of it, simply by being African-American at a time when race severely limited one’s educational, work, and business opportunities. Yet both were survivors who thrived despite setbacks and mastered an art that endeared them to generations of fashion-conscious women.

Ann Lowe was born Ann Cole in rural, segregated Alabama, where an elementary education for black children would not prepare them, math-wise, to be able to manage a business. She instead learned to sew from her mother, Janie Cole, and her grandmother, Georgia Thompkins. Her grandmother passed on techniques grounded in the 19th-century styles for ball gowns. This training was very refined and can be seen in the inner construction and boning of Lowe’s gowns today.

Ann had the “precision and patience” to master sewing, which was not easy for children, cutting patterns at age 10 and fashioning flowers out of fabric scraps. These skills elevated her work opportunities above that of the more physically taxing laundress or housekeeper—the normal work for black women.

Ann was discovered by a wealthy citrus grower’s wife while working in a department store. The woman, Josephine Edwards Lee, noticed Ann’s smart attire and asked where she could purchase clothes like that. When she learned that Ann had designed and sewn the outfit herself, Lee invited her to move to Tampa, Florida, where she became the live-in designer and seamstress for a family with many daughters.

The social calendar of the girls and their friends required many gowns and soon, Ann Cole became well known in Tampa. It was said that for your attendance at any big social event to be a success, you needed to be dressed in one of Ann’s innovative, flattering, and confidence-boosting creations.

Ann was a black designer designing for an exclusively white clientele at the time. She could not have a shop in the “white” areas of town, yet that did not stop her clients from coming to her.

This was a very good turn of events for a young wife and mother whose first husband was not supportive of her career (as was the case with the second one later on).

Ann dreamed of further honing her skills by studying fashion design in New York. For this and her future shops in the Big Apple, she had both her savings and the aid of her many clients, who treated her as a friend. This was in the 1920s when New York was much more open to people of color and yet it was not easy for one to study in a fashion school.

The French director of the school could not believe she even had the money for tuition until she showed him her bank account. Ann had to study in a separate classroom from the white students. But soon the French teacher was showing her work to the others, and Ann’s classmates started going to her room to watch her work.

A gifted artist with real perseverance who was willing to design even for other fashion houses, she was able to make it through both the Great Depression and the war, which many businesses did not survive. She went through setbacks such as shop closures every so often but looked instead for ways to continue designing.

By the mid-1940s, she had a growing clientele that included Jacqueline and Lee Bouvier plus their mother, Janet Auchincloss. Through Sonia Gowns, she created the gown she herself hand-painted for Olivia de Havilland, who wore it when she was named Best Actress at the Academy Awards. By the Fifties onwards she was at her peak, becoming financially comfortable though living simply. She simply focused on her love of design.

In 1949, while reporting on the Paris collections of Christian Dior, Balenciaga, and Jacques Fath for the New York Age, her client Marjorie Merriweather Post (the heiress of Post cereal) introduced her to acquaintances as “Miss Lowe, the head of the American House of Ann Lowe.” It was significant that such a prominent woman should credit her black designer for what she was—a couturier.

Her son Arthur managed the business side for her but when he was killed in a car accident in 1958, she could not manage the business end and became indebted. She would design for places like Saks Fifth Avenue, through which so many society women were able to purchase her gowns, but it ruined her financially. She could not comprehend that the cost of the gowns she was selling there was far more than the prices she was selling them for.

By the time she ended this relationship with Saks and began to manage her own shop again with the help of her sister, her eyes began to fail. Yet she continued and persevered, creating gowns almost until the end of her life.

When she was already on her hospital bed and could barely see, she told a reporter that “there are still a thousand ideas for dresses in my mind, dresses which I see in great detail.” Her joy was not in material possessions but in the sheer fulfillment of creating lovely debutante and ball gowns, wedding gowns, and trousseaus. She trained a number of seamstresses and inspired other young black designers after her, including a niece.

Though Ann Lowe did not crave the spotlight, we should be happy that it shines now on her remarkable life and a collection of well-preserved gowns, which continues to inspire fashion dreamers today.