Feathers for festive dressing

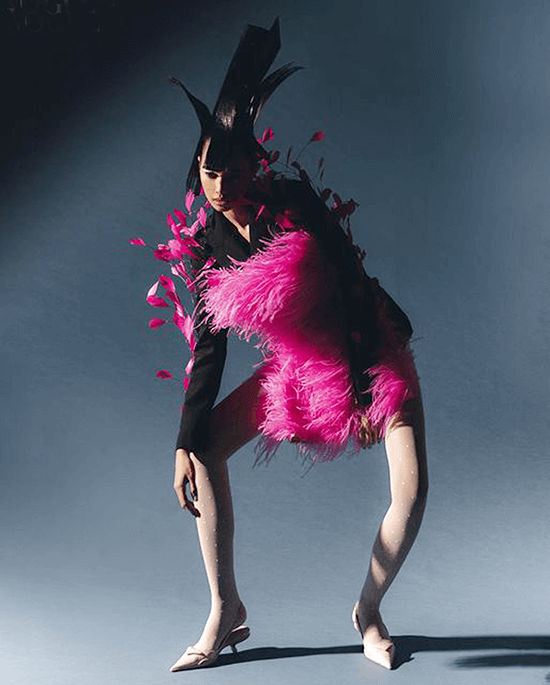

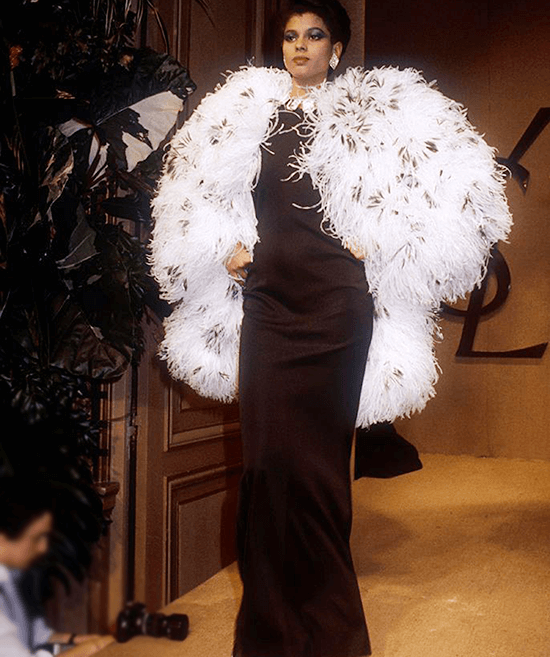

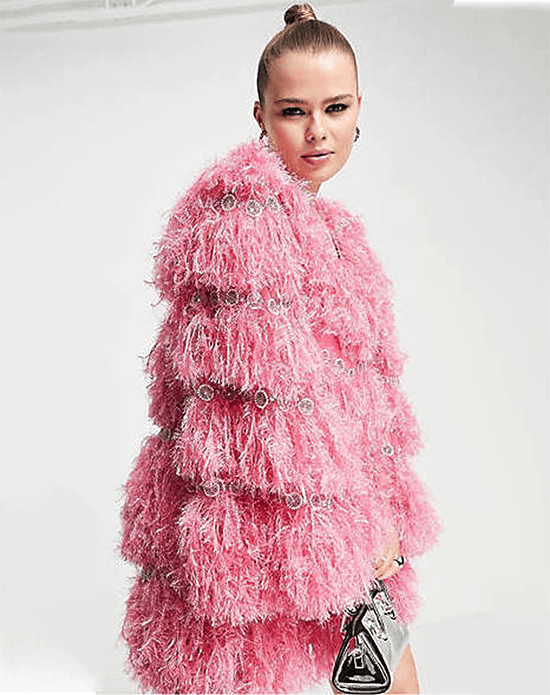

There’s always an air of festivity, not to mention glamour, when feathers are part of the proceedings. Plumes are abundant this season, both in daywear and eveningwear, and they are not going away with the spring-summer shows proffering them both as actual embellishments and in referential form through simulated and printed feathers, wings, and birds.

Why are we so obsessed with feathers and avian things? From prehistoric times, it was the only creature that man shared the ground with but could take flight and rise above him with all the splendor of its wings made of the most exquisite plumes. He could not help but covet them for adornment, as discovered by Marco Peresani in a Neanderthal settlement near Verona, Italy. Of the 22 bird species that he found de-feathered, most were not known to be good food sources and only the wings had cut, peeling and scrape marks. “They removed only the remiges, which are the longest and more beautiful feathers,” the paleoanthropologist said.

The act of adorning the body with elements of nature like pelts, leaves and feathers was a way of honoring the protective qualities of the land across ancient cultures around the world. The more unusual and rarer the items were, the higher the societal rank for the wearer.

In precolonial Philippines, the fascination and reverence for heights that birds could reach inspired the use of their feathers for a correspondingly elevated status, adorning the headdresses of tribal leaders and war heroes. Among the Ilongot and Ifugao, red feathers symbolized power and were worn by the successful headhunter together with the red casque and beak of the hornbill. The Kalinga inserted red plume ornaments under their head scarves, worn by men during feasts. The B’laan had palm-leaf hats covered with parallel bands of rattan and crowned with long chicken feathers.

From the 12th century, Venice’s annual Carnivale celebration had participants wearing papier-mâché masks exuberantly decorated with feathers to conceal one’s identity—making the festivities a democratic one where everyone from all classes could mingle with one another, playing out illicit acts like gambling and clandestine affairs.

The celebratory nature of feathers was universal, as seen with the expansion of trade and imperial conquest. When the Portuguese colonized Brazil, they brought their Carnival traditions, which began as formal balls among Portuguese high society but were eventually appropriated and overshadowed by the Afro-Brazilians, who added lots of color, music, dance, and lavish costumes. Although initially segregated, the celebrations eventually merged in the 20th century to become the now famous Carnival, where samba schools outdo each other with the most over-the-top floats, costumes, and headdresses.

A similar spirit can be seen in the Philippines’ Ati-Atihan festival in Aklan held in honor of the Santo Niño, where plumes appear in colorful costumes and headdresses.

Going back to Europe, expeditions brought back exotic feathers, just like the one led by Ferdinand Magellan, who died in the Philippines but whose surviving ship made it back to Spain with the fantastic feathers of the bird of paradise from New Guinea.

During the Renaissance, the use of feathers was predominantly for men, as seen in paintings of Henry VIII in a feathered beret and the dandy German accountant Matthäus Schwarz in a headdress of 32 ostrich feathers that was 18 inches high and three feet wide. Just like their tribal counterparts on the other side of the world, feathers comprised a desirable look of power. By the time of Louis XIV, the plumassier became a significant profession to cater to all the feather requirements.

In the 1700s, however, plumes became almost feminized, save for military displays. Marie Antoinette led the pack with feathers on her signature toque updo that reached three feet high. After the French Revolution, the simplicity of neoclassicism placed plumes on hold, only to resurface when the monarchy was restored in the 19th century, as women’s journals filtered a taste for excess down to the masses, making feathered hats such a craze that by 1886 in New York, the ornithologist Frank Chapman observed some 40 native bird species on women’s hats, some with a whole bird attached.

With museums finding it more difficult to obtain exotic birds, a publication lamented that women were “the indirect instigators of this slaughter; all that can be hoped for is that the freaks of feminine vanity may take some other, less harmful direction.”

The desirability translated to the price offered to heron feather bird hunters: $32 per ounce, making the plumes worth twice their weight in gold. Herons, among other birds, were on the verge of extinction. In 1902, over 1,600 packages of plumes were sold at just one London auction house, requiring the killing of 192,960 herons at their nests.

While women were condemned for their role in consuming feathers, they were also instrumental in raising awareness the way American socialite Harriet Hemenway led a boycott of feathered hats, leading to the formation of the National Audubon Society and passage of the Weeks-McLean Law, which outlawed market hunting and interstate transport of birds. By 1913, international plume markets started shutting down as feathered fashion fell out of favor.

They would make a brief appearance during the Jazz Age in the 1920s as feather boas were draped across the shoulders of flappers dancing at nightclubs and were used by Parisian stars like Mistinguett and Josephine Baker to enhance their movement onstage.

Feathered hats made a comeback in the 1930s to early 1960s, but lost popularity in the subsequent decades, as hats were no longer a standard item of women’s daywear. Entertainers in the ’70s and ’80s like Elton John and Cher brought them back onstage and the disco scene would be enlivened by bold feathered looks.

Feathers have since evolved to be sustainably collected, manipulated and dyed so that designers and consumers can use them with a clear conscience. There are those who, just like with leather and fur, would rather not have animal parts on their bodies, making faux feathers like those in the garments of ASOS an option. The simulation of birds and feathers through prints and fabric manipulation is another, the way Cary Santiago made those beautiful pieces for Ternocon. This way, you can have your connection to those beautiful, winged creatures of nature while leaving the actual birds alone.